Sweden is a social-democratic beacon with one of the world’s deepest stock markets. Contradiction? Martino Comelli argues that welfare states build financial markets through social policy design. Funded pensions and housing subsidies create investable assets; generous public pensions crowd finance out. The same welfare spending level can produce radically different capitalisms

Finance dominates headlines and economies alike. Pension funds, insurance companies, and investment firms control capital rivalling entire GDPs, shape corporate governance, move labour markets, and influence government policy. Yet at the household level, most people barely see it: only about 30% of British households and 37% of Americans report any financial income during their working lives, and the amounts are usually modest. Finance shapes everything, but it rarely touches everyday bank accounts.

Why do some countries have vast financial markets while others do not? The answer lies not in how much governments spend on welfare but in what they spend it on

So where does all that capital come from? And why do some countries have vast financial markets while others do not? The relationship between finance and social policy is surprisingly underexplored. My recent research with Viktor Skyrman using OECD data suggests welfare states themselves are partly architects of financial markets. The answer lies not in how much governments spend on welfare but in what they spend it on. Some programmes actively build financial markets; others act as circuit breakers that reduce households’ engagement with finance.

The Swedish puzzle

Sweden, often seen as a social-democratic example, also boasts one of the world’s largest institutional investor sectors and deep stock markets. This is not a contradiction. It traces to pension reforms in the 1990s that introduced funded components alongside traditional public pensions. Policy design created investors. The Netherlands offers a similar case: Dutch pension funds hold assets exceeding 140% of GDP, not despite generous welfare, but because retirement security was structured through occupational funded pensions.

Workers contribute, but they rarely control how that capital reshapes the economy. Pension cheques arrive eventually, but decades of investment decisions happen without you.

‘Assetisers’ and circuit breakers

Welfare policies influence finance in two main ways. Some embed households into markets. Housing subsidies, for example, stabilise rental income and property values, transforming homes into investable assets. Private health insurance schemes do the same: guaranteed revenue streams populate institutional portfolios. These policies ‘assetise’ welfare, creating the very assets finance trades in.

But public pensions? They’re kryptonite for finance.

Welfare policies such as housing subsidies and private health insurance schemes ‘assetise’ welfare, creating the very assets finance trades in

Generous pay-as-you-go pensions crowd out institutional investment: no household contributions flow to fund managers, no capital pools seek returns, no institutional investors exercise power over corporations. These programmes decommodify welfare, reducing the structural need for households to engage with financial markets. Family benefits function similarly, transferring resources directly without generating investable flows.

The slumbering giant

Most discussions of financialisation focus on pension funds and equity markets, the Anglo-American model. But elsewhere a different pattern emerges. In Germany, France, Belgium, Japan, and Korea, insurance companies dominate: the ‘slumbering giant‘ of financialised capitalism. They sell products that layer on top of public provision (supplementary health coverage, life insurance, disability products), converting stable household income into long-term capital market investments.

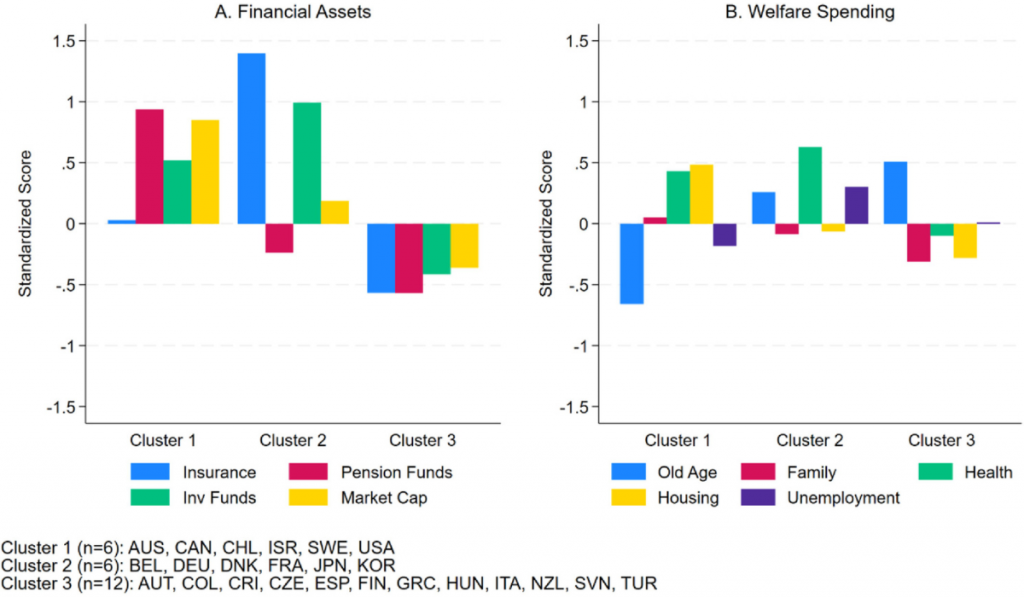

My research identifies three distinct clusters:

- Liberal economies and pension-led systems (US, Canada, Australia, Sweden, Chile) where pension funds dominate, equity markets are deep, and public pensions are modest.

- Insurance-driven systems (Germany, France, Belgium, Japan, Korea) where moderate welfare spending stabilises income, enabling large insurance-based institutional investors even without expansive pension fund sectors.

- High public-pension systems with minimal financialisation (Italy, Spain, Greece, Hungary), where generous old-age programs coexist with shallow capital markets.

Across these clusters, the logic is consistent: welfare design, not spending level, shapes the depth and structure of finance.

How much finance is enough?

This reframes debates about welfare and finance. The same level of social spending can either shield citizens from markets or build the financial architecture that fuels asset inflation. Countries with housing subsidies and funded pensions may combine low-income inequality with high-wealth inequality, because life chances increasingly depend on property and portfolio performance rather than wages.

The findings also raise questions for policymakers: how large should finance be relative to the economy it serves? When is it preferable to channel resources into financial markets, and when should welfare act as a circuit breaker?

Public pensions may seem old-fashioned now, but they provide security without locking households into markets or driving asset inflation that prices younger generations out of housing

Public pensions and family benefits may seem old-fashioned compared with asset-based solutions. But they provide security without locking households into markets, without generating trillion-dollar investment pools, and without driving asset inflation that prices younger generations out of housing and wealth. Sometimes, the non-assetising path may simply be better.

Finance is not something that happens to welfare states from outside. Welfare states build finance, selectively, through policy choices. Pension reforms, housing subsidies, and insurance mandates are decisions about what kind of capitalism to construct. We can make different ones.

It was never just finance. It was always your pensions.