Six months ago, my girlfriend and I were on a beautiful Hawaiian vacation. It was one of the happiest weeks of my life. We landed in Kona and shared a sunset dinner by the water. We watched Kīlauea erupt together, lava shooting hundreds of feet into the sky and soot falling from the air like snow. We laughed. We snorkeled. I remember feeling Amy rest her head on my shoulder as we watched the sky burn itself out over the island. It was one of those moments where time seems to slow. Where all you want is for the weight of another person, the sound of their breathing, to stay exactly the same forever. I held that feeling more tightly than I realized at the time.

It was beautiful. It was also haunted. Haunted, because while we were laughing and taking pictures, I was carrying a thought I didn’t want to say: something is wrong.

For weeks before our vacation, I could feel that my girlfriend had a brain tumor. Not in a mystical way. But in the mundane way that comes from living with someone and noticing the small, unexplainable things. Amy was in constant fatigue. Her period inexplicably disappeared for 6 months. Her bone density was poor. All of this despite averaging 10 hours of sleep per night and consistent physical activity.

We met with some doctors. They initially fixated on the fatigue, citing that it could be any of allergies, stress, vision problems, or burnout. One even suggested that some people just need 10-11 hours of sleep to feel normal. But no one told us exactly what was wrong.

Day by day, Amy experienced more moments of fatigue and sadness. It didn’t just inflict fear in me. It made me feel time. I felt scarcity. I felt pangs of anger every time I wasn’t fully present in the moment with her while dark thoughts pulled me away. Every day we waited to see the next doctor, I tried to salvage moments of joy amidst my running imagination.

When we got back from vacation, Amy turned 25. We had a lovely 12 course dinner. Her roommates and I threw her a surprise party at home. People showed up with less than 24 hours notice on a Monday night. She looked tired but happy, held by all this love.

And I remember thinking; quietly, privately:

I have no idea what her 26th birthday will look like.

Because earlier that day, Amy had a doctor’s appointment. While I waited for her, my mind juggled between two realities: one where this is nothing, and one where everything is about to change.

Then I saw the images:

My life partner has a brain tumor.

The diagnosis was both devastating and relieving.

Relieving because it wasn’t metastatic. It wasn’t widespread. It wasn’t the worst-case story our brains had been writing.

Devastating because it was still a brain tumor.

Amy has a prolactinoma: a tumor of the pituitary gland that causes the body to massively overproduce prolactin. Prolactin is best known for helping mammals produce milk for their babies, but is involved in hundreds of processes, including menstruation. Clinicians often call it “chill,” because it usually doesn’t spread and often responds to dopamine agonists like Cabergoline.

Amy’s case hasn’t been chill.

Her prolactin levels were supposed to be between 5–20 ng/mL. They were 330 ng/mL. The tumor was large, caught late, and growing quickly on the back of her posterior pituitary gland. Normally, you can try Cabergoline for a few months to see if it shrinks the tumor and lowers your prolactin. But according to her care team, if the tumor grew by even 20%, it would threaten her vision.

Surgery was the only option. Prolactinoma resection occurs through a process called a transnasal transsphenoidal surgery. The procedure involves passing a fiberoptic cable up one nostril and surgical tools up the other, cutting an opening in the nasal septum and sphenoid sinus to reach the base of the skull (sella turcica).

Normally, this surgery is very low risk: the majority of these tumors occur on the anterior (front) pituitary gland, which is easily accessible via the nose. She has a less common posterior (back) pituitary tumor. Her tumor was large and caused intracranial pressure, so the surgeons needed to perform a riskier procedure to lift the pituitary gland to access the tumor.

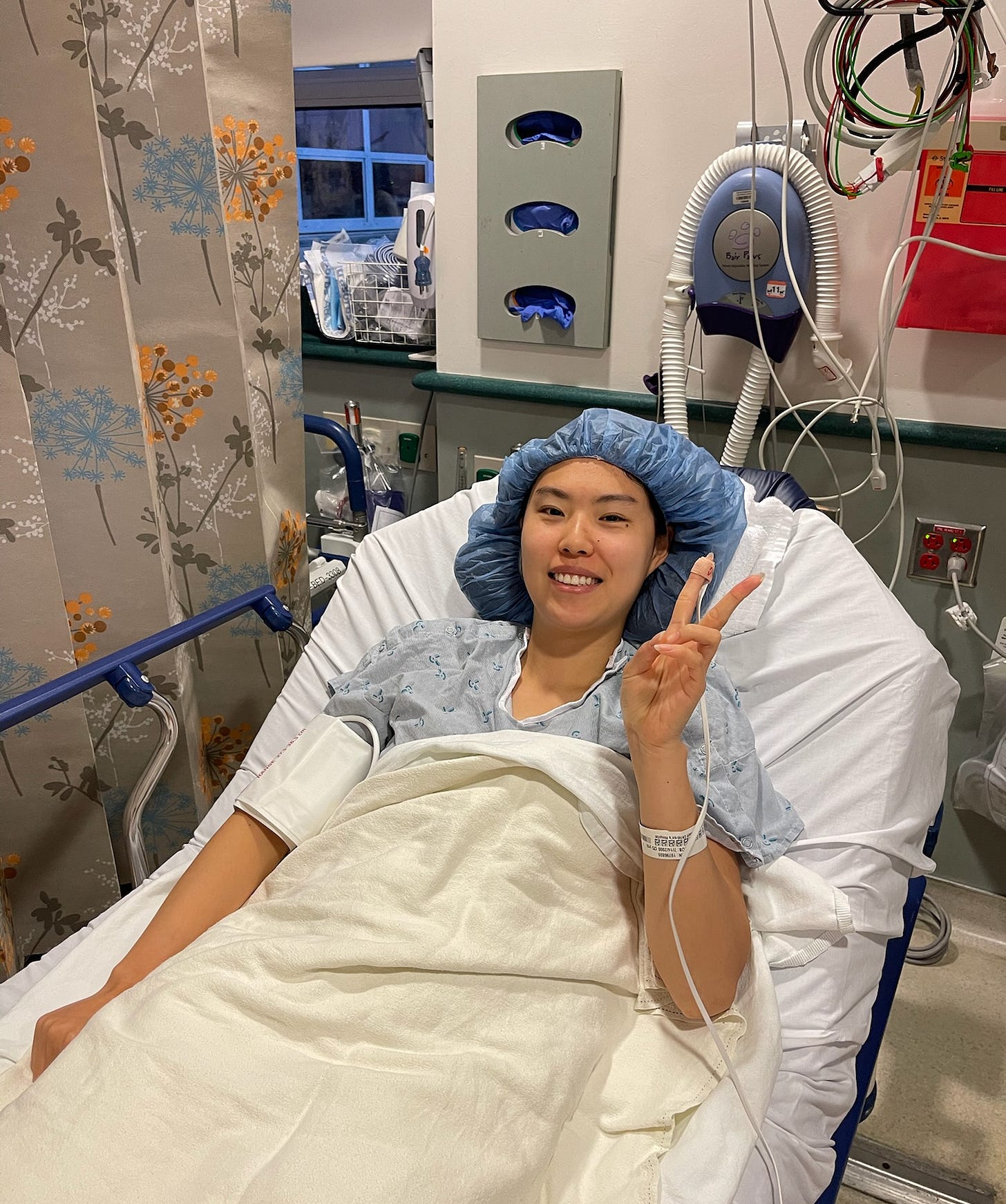

The morning of Amy’s first surgery, I wrote a journal entry:

It’s currently 9:36am and I’m sitting in a crepe place near UCSF. Amy is currently getting her tumor removed. Despite my confidence that she will be okay, now and then, the reality of the situation hits and I feel a child like fear that things won’t turn out okay. I’m scared.

I’m keeping this record of how I feel in this moment because it’s important to allow myself to feel the terror of this moment, however painful. The love of my life is on an operating table, and our future together depends on the actions of a few doctors right now. That’s scary.

I’m also sad that I can’t be with her the very moment she wakes up. I promised to be there, but the hospital restricts this until you have your own room. The live updates I’ve been getting are reassuring. I would have moved worlds to get her the care she has by default. We are so lucky.

Nothing else in this journal is as important as how I feel about her now and in the future. I’m excited to see my wife soon. I’ll think back today when we meet our children. – AR

The first surgery removed 80% of the tumor. Her prolactin levels decreased from 330 ng/mL to 60 ng/mL. Not quite the 100% cure we were hoping for or the acceptable 5-20ng/mL range, but her condition appeared more manageable.

Amy’s recovery was rough. She couldn’t bend. I played human-forklift for her backpack and shoes. I held her hand when the intense headaches left her bedridden. I read every page on r/prolactinoma for solutions to her nasal congestion; she couldn’t blow her nose for fear of triggering a spinal fluid leak. I bought a humidifier that left our bedroom musky and damp. She couldn’t use straws or taste food, and still does saline nasal rinses to this day.

Up until Amy started having symptoms, I worked day and night as an independent consultant on projects advancing human health. In the first half of 2025, I worked on several projects and presentations that have been seen by some of the richest people on Earth, Vitalik, and tons of Tier 1 VCs.

But when conditions got worse, I happily chose to be Amy’s full-time nurse. I downsized to 10-20 hours of part-time consulting, I feel immense gratitude to have had a work structure that allowed me to be so present.

Eventually, Amy was well enough to travel again, and we celebrated our wins by taking a vacation to the base of Mt. Everest. I remember sitting next to her looking up at the world’s highest peak. I thought to myself, “Amy’s surgery is this mountain that is now behind us.”

September 25th was the marathon of follow-up appointments. One with arguably the top prolactinoma neuroendocrinologist in the world, one with her ENT, and one with her surgeon. We were expecting the doctors to treat her with dopamine agonists to kill the residual tumor tissue. We were expecting her to finally have a “chill” brain tumor.

But Amy’s tumor continued to grow rapidly and had granulated features that made it more likely to spread if untreated. Within weeks of surgery, her prolactin rose again to 100 ng/mL. The prolactinoma neuroendocrinologist warned us that he had seen patients with similar tumors who now faced surgery #4 and radiation treatment #6. Medication was technically an option, but given the information we were provided, it felt like suicide.

After that appointment, we sat at a Starbucks waiting for the next. I watched Amy swirl a straw around her drink. A straw I then watched her remove. I almost lost it. But I had to keep looking forward. Right there, I promised her that if things were really bad, we’d go to city hall that afternoon. We’d get married and spend the rest of our time together.

We met the surgeon. He explained that we had a 90% chance at a full cure with a second attempt. We were happy to hear that the remaining tumor healed in a way that made it much more accessible, but confused to have two medical titans paint two pictures of different levels of severity.

The chance of a full cure shook us out of despair.

More time off work. More space for prolactin-induced mood swings. More occasions where I didn’t feel present with my closest friends due to emotional burnout. I pinned all of my hopes on this 90% probability. And I hoped that even if the odds were somehow not in our favor, surely the tumor would be so small that the cabergoline could then treat her.

But I also knew that every time you surgically manipulate the pituitary gland, you increase the risk of permanent brain damage. You increase your risk of getting a condition called diabetes insipidus, or DI which requires a lifetime of cumbersome medication.

—

I got the call. The surgery was proclaimed a complete success with no complications! Her surgeon described how they thoroughly examined all suspect areas and removed all suspicious tissue. I finally let myself relax. Amy was in a daze, but recovering well. She even got her own room this time, so I was able to stay overnight.

The next afternoon, I took a walk to get Amy a caffeine-free, strawless boba with her care team’s blessing. I returned while in the middle of a phone call with a friend when Amy signaled that I needed to get off the phone immediately. She just got back her post-op prolactin levels.

Prolactin has a half-life of ~50 minutes in our bodies. Because of this quirk, we can tell within 24 hours how a prolactinoma resection went because one’s prolactin could only be elevated if you’re actively secreting excessive amounts. This is how we knew the first surgery was not a complete success when her level was 60ng/mL.

This time, her level was 65ng/mL. Higher than after the first surgery.

—

My mask came off. I was completely beside myself. I sprinted over to the nurse’s station and demanded to speak to the surgeon, the resident on call, anyone who could explain this, immediately. It’s the closest I’ve ever come to screaming at someone who didn’t deserve it.

A nurse came in and rolled Amy off to get an expedited post-op MRI, something that normally happens 6 weeks after the surgery. After she left, I fell into a fetal position and cried. All the months of being the rock caught up to me at once. I couldn’t hold it anymore. I believed the tumor had spread beyond the pituitary. My whole world collapsed in on itself. My future wife was going to die. I was all but promised this would be over. It was so unfair. I was so tired.

Since Amy’s second surgery, we’ve spoken with most of the world’s leading prolactinoma experts. Yet even they disagree: some see residual tumor in Amy’s post-op MRIs; others don’t. Some advise cabergoline; others recommend a third surgery. The uncertainty is maddening, but at least they all agree it hasn’t spread.

A third surgery would have a 5-15% chance of permanent pituitary dysfunction, so Amy’s taking cabergoline. So far, she’s only experienced mild side-effects. We’re optimistic.

When we asked one of the top prolactinoma experts what causes these tumors, he shrugged: “It’s random, but there’s possibly some genetic weighting.” Amy’s mother may have had one.

That’s when a horrifying but clarifying thought hit me.

We want children one day. If there’s a hereditary component (more on this in a future post), there is a non-trivial chance our kids could develop brain tumors. Given how early Amy’s symptoms started, we would have ~20 years before any child of ours might show signs.

It also happens that today we are on the cusp of a transformation in AI-driven science.

Do I wait for that transformation to arrive? Or do I choose to use the tools available and deepen our understanding today?

If there’s one thing this year taught me, it’s that the future is uncertain, and you can wake up one day with a “chill” brain tumor just after turning 25. So I’m choosing to act.

Prolactinomas have a standard of care, yes. But “standard of care” often means “the least bad option we currently have.” The gap between what the best doctors know and what is actually actionable for patients is shockingly wide. I’ve watched in real time how slowly and incompletely scientific knowledge translates into decisions in the clinic.

At the same time, I’ve consulted with researchers who are building “AI Scientist” systems – agents that can read thousands of papers, propose hypotheses, design experiments, and reason about biology far beyond a human’s cognitive bandwidth. The juxtaposition is impossible to ignore.

So here’s the real question I’m trying to answer:

Can one motivated researcher with undergraduate-level biology training, armed with state-of-the-art AI scientist tools, and open data, meaningfully advance our understanding of brain tumors?

This isn’t entirely foreign territory for me.

I used to do biophysics research at Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute under Stavros Lomvardas. I’m no stranger to molecular biology, neuroscience, or scientific reasoning. And I’ve spent the last few years embedded in the techbio and AI ecosystems, most recently as an investor at Side Door Ventures. I have above average knowledge about biology. A future state where I comfort myself with thoughts like “there was nothing I could do anyway” is completely wrong, self-soothing bullshit.

I’m committing to work on this full time. I’ve been reading papers about prolactinomas and trying AI research tools.

And I’m inviting you to be part of my journey.

I’ll share my procedure, the papers, the tools, and my goals in much more detail next week. After that, I’m going to share my thoughts on how the tools I’m using are uplifting my rate of learning (most likely a qualitative analysis).

I’m hoping to meet people that are excited to help cure and treat all human diseases. These are some archetypes of people I’m trying to meet and why:

-

Scientists working at the intersection of AI x Bio to tear my ideas apart and give me new ones.

-

Techbio founders eager to get feedback on their tools.

-

Neurotech founders and scientists that can help spark new research directions and ideas!

-

VCs that invest in tangentially related places, as they will likely be connected to the people above. Also happy to refer over cool companies 🙂

-

Foundations and grants writers that fund independent research projects like this! I’d like to both feed myself and have a budget to pay for tools.

-

Here’s my calendar. Before whatever interesting thought you have now escapes you, grab time and write it in the invite!

-

There are a bunch of ways to DM me. X, Substack, and LinkedIn all work. Choose what’s easiest for you. My VC email, ajr@sdv.vc also works. Again, don’t let your ideas escape you!

-

I work out of Frontier Tower in SF Mon-Wed. You can find me on the 15th floor and say hi. Lmk you’re coming, and I’ll sign you in!

When I was deciding to quit my consulting work to work on Amy’s brain tumor, I thought about what I want to be known for. I realized that I don’t care to be known for my intelligence. I don’t care to be known for my accomplishments.

I want to be known for my capacity to love.

—

Thank you to everyone in my life that’s given me courage over the past year. Thank you to Jane Zhang for extensively helping me improve how I tell this story. Thank you to Amy for being the best partner I could ask for. As difficult as it has been, this experience has filled me with purpose and determination. I’m grateful.

Amy wrote about this experience from her perspective beautifully here and here. I’m still in awe of her courage and gratitude for life.