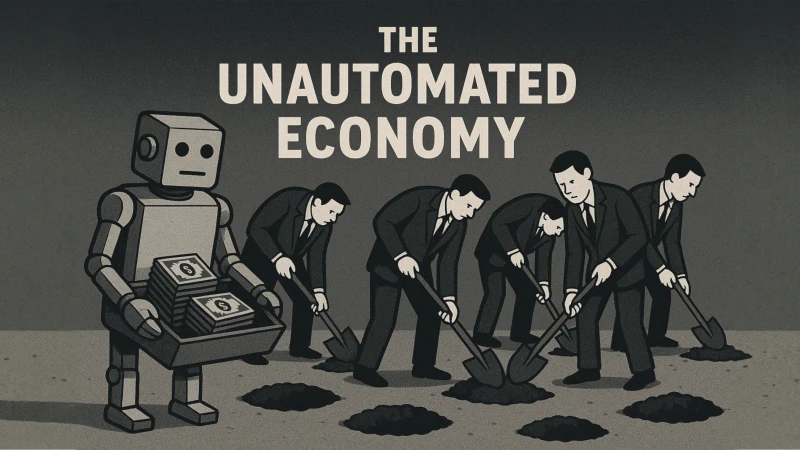

UnAutomating the Economy: More Labor but at What Cost?

Imagine an economy where robots, AI, and advanced machines do much of the work that used to require human labor. Not a dystopian or utopian future of full automation—just one where most goods and services can be produced with far fewer people working than we see today.

In this world, wages matter less. Most people live on Universal Basic Income (UBI) while a smaller human workforce still earns extra through paid jobs or running businesses.

Surprisingly, this automated economy doesn’t look so different from ours. The average person’s income can be just as high. Prices, markets, banks, and firms still function the same way. The only real difference is this: Fewer people have to work to buy what the economy produces—because income no longer depends primarily on wages and jobs.

But here’s a twist: Now imagine society doesn’t like this outcome. A cultural movement emerges to insist humans should or must work in jobs. For members of this movement, paid work isn’t just income; it’s duty, dignity, identity.

Unwilling to ignore the public’s wishes, policymakers acquiesce to this movement’s demands. They cut UBI—making people need jobs more—and also push central banks to flood the economy with cheap credit so more firms can borrow money and hire more workers.

The result? The economy gets unAutomated. More jobs and wages come to exist not because the market actually needs more workers, but because people are taking jobs back. By removing UBI and stimulating borrowing instead, policy causes employment to rise above what’s efficient.

We might call this overemployment: a state of the economy where labor is used and paid for not because it’s needed for production but because people feel they deserve jobs and have used financial policy to engineer that outcome.

Overemployment might be dismissed as not a real problem by people who believe more employment is better than less; nevertheless, this overemployment comes at a cost.

Resources that could go into producing more goods and services are instead used to keep people working. This means consumer welfare falls: People are poorer despite there being more jobs. And because the central bank has to prop up employment with easier private sector credit, financial markets become bloated, speculative, and fragile—making recessions and crises more likely, not less.

Another cost worth mentioning: Natural resources which could have stayed in the ground become used up to support superfluous employment; generating unnecessary pollution to at least some degree.

There’s all kinds of problems we might expect if robots started reducing the need for labor but humans kept creating jobs anyway.

Here’s the surprise ending: This isn’t just a sci-fi thought experiment. Whether we realize it or not, this story reflects how we already organize our economy today.

We behave as if human work is an end in itself, rather than a means to produce the things people want. We stimulate employment even if it means destabilizing the financial sector. We assume that more jobs automatically means a healthier economy—even though more income and fewer jobs might make us better off.

In that sense, our economy today may already be “unAutomated.” We’re holding onto work even as labor efficiency rises. This drives waste of human time, natural and industrial resources, and economic potential. It blinds us to the fact that Universal Basic Income isn’t a future response to automation; it’s a macroeconomic tool we could use today to decouple income from jobs and better align work with genuine economic need.

If policymakers stopped treating full employment as the highest economic goal, and instead calibrated UBI to match the real productive capacity of the economy, people could buy what robots and machines can produce without generating work for the sake of wages.

In other words: Overemployment may already be the problem we should be worrying about—not joblessness. Policymakers, economists, and citizens need to rethink why we prize paid work so highly.

Whether we realize it or not, today’s macroeconomic policies may already be steering us toward waste, inefficiency, and unnecessary labor.

In theory, UBI is a simpler, better, more efficient way of delivering income to people than what we’ve been doing: cheapening debt to generate jobs. A properly calibrated UBI is not an emergency measure or a concession to laziness—it’s how we should have been responding to labor-saving technology all along.

For a more thorough treatment of these ideas, see my working paper, “The UnAutomated Economy.”