I recently started coding. And by coding, I mean telling AI to code and watching it without understanding of what it’s doing. But as I summoned new elements on my work’s website and my girlfriend and I played a multiplayer card game I “built”, I started to feel like a magician.

My head started spinning. Could I call myself an engineer yet or did that require another month? Which tech company should I put out of business? I started to imagine making millions off of my one-person startup like that one guy I heard of once, in a headline I didn’t click on.

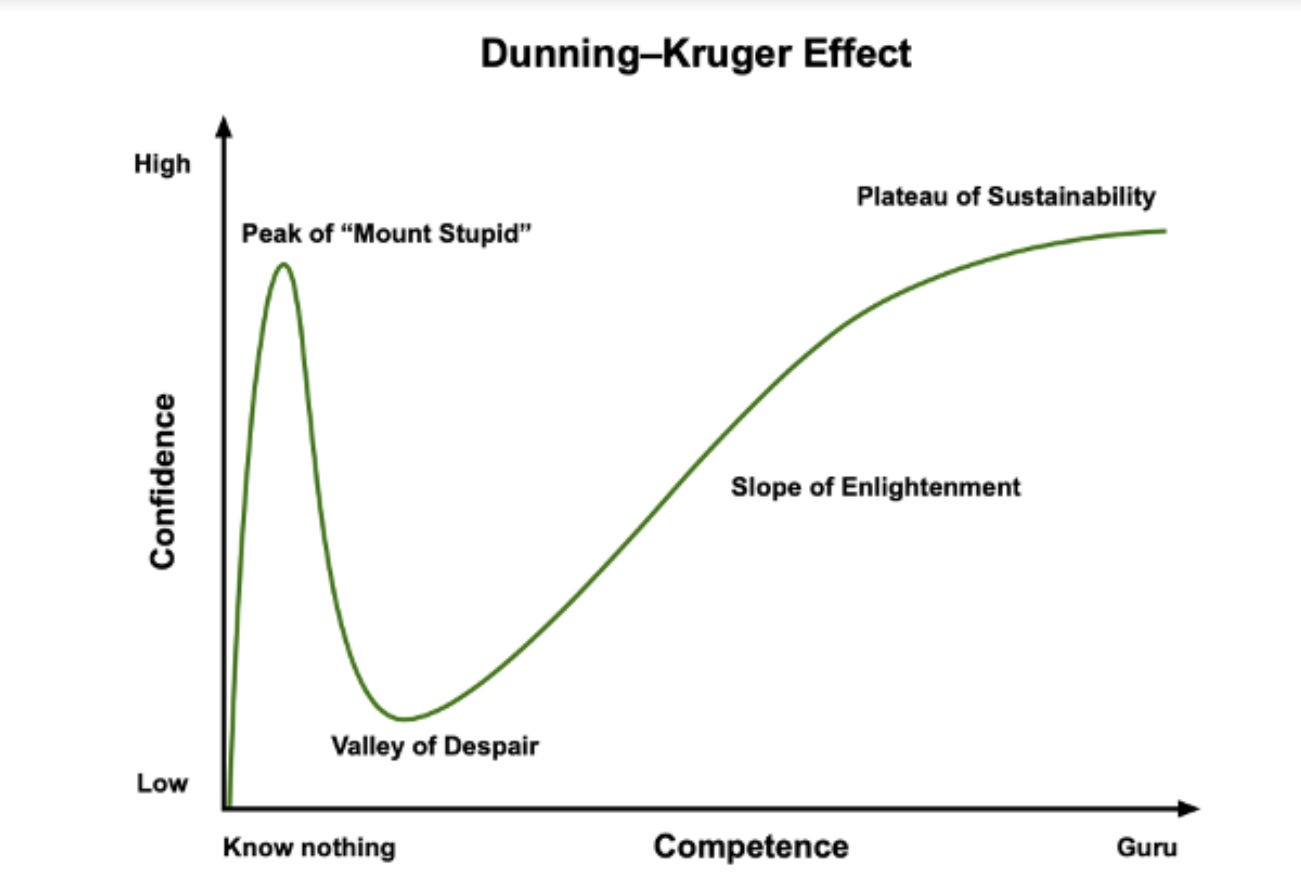

In Dunning-Kruger terms, I’m at the Peak of Mount Stupid. Building so much as a to-do list app from scratch would send me into the Valley of Despair.

By its name, Mount Stupid is not a place you want to be. But I think there are benefits to having high confidence, even if you don’t yet have the competence to support it. As long as you’re aware of it, that is. “I’m sure I can make that jump, I’ve always been athletic” might be your last words. At work, nobody wants to hear impassioned speeches about something you have no (real) idea about.

But there’s something magical about sucking at something. It keeps you from overthinking and helps you ship more work. This “underthinking” can often get better reception because your own snobbery doesn’t get in the way of creating something people want. In fact, it’s the opposite.

Edward Chisholm’s memoir A Waiter in Paris (which I loved) earned glowing reviews, was shortlisted for prizes and maintains a 4+ rating on Goodreads (which is impressive, considering that Goodreads might be the snobbiest community on the internet).

Chisholm is no veteran Substacker whose work culminated in this book. The book didn’t top off a decades-long journalism career. No art school. Edward Chisholm was, well, a waiter in Paris. He just wrote a book about it.

Anthony Bourdain experienced breakout success as a full-time chef who submitted an essay to the New Yorker.

People who skip the “work your way up”, do the art form and infuse it with their life experience exist in every profession: The successful company founder who’s a mediocre programmer, the dental technician who sells millions of board games, the product manager who accidentally becomes one of Substack’s highest-earning creators.

On my bad days, I torment myself with the question: “Why does [Person X] have exactly what I want when they have less practical experience, less writing skill, less… everything!!! I deserve this!”

And then I torment myself even more with the answer: “Because they’re actually doing it.”

I think it’s precisely their inexperience and lack of skill that lets them not overthink, which directly leads to more doing it. That’s why they often get so much of the rewards: They create a lot and share their work often because their artistic mind isn’t paralyzed by comparison, overthinking and judgment.

I consider myself a good writer. It’s the craft I most care about. But in writing this down, I worry the two preceding sentences are rhythmically too similar, ponder whether a shorter second sentence in this section would improve the reading experience and decide not to, because, well, it’s a good example of the type of overthinking I’m writing about.

While yes, it’s great to have nuanced writing skills like this, it makes me write less because the act of writing becomes a heavy-handed ritual, not an enjoyable art. The result of it has been that I write little, publish less and get none of the results.

Being more skilled has made writing less fun.

And among the rewards beyond the process itself? Readers love writers who regularly publish. Most people also aren’t as judgmental as I am of my work. Even if you like fine dining restaurants, you don’t need to eat a wagyu ankle fermented for 7 fiscal quarters with a goat cheese foam and Bulbasaur seeds for every meal.

This is even true for me:

When I go to a museum, I don’t get the most enjoyment out of realistic paintings with impressive technique. I often love paintings that make me feel something, even if “I could’ve made that.”

There’s even something boring in polished realism. This painting is technically impressive in its realism (especially for the 1600s!).

But I feel nothing. Yet this technically much less impressive painting does evoke all kinds of memories and emotions:

It would take more training to reproduce the former, but I’d rather have painted the latter. The same is true for writing: Most people want to feel something, learn something or be entertained.

In fact, the rawness of the second painting’s technique adds to its expression, the same way Anthony Bourdain’s raw honesty about the restaurant business made his writing much more enthralling than a 3-star chef’s sophisticated description of consomme could have.

In fact, more sophisticated technique can obscure the very thing you’re trying to do. Here’s the Diebenkorn painting, made more realistic (and thus totally ruined) by AI.

I want to cultivate this in my writing. Not abandoning polish or producing bad writing, but to focus on what helps me write without overthinking. To make things that connect, not impress. If my current approach to writing leads to me not writing, something needs to change. I need underthinking.

As my mind defaults to thinking a lot (which isn’t helping), I probably need to get comfortable with worrying that I might not be thinking enough, and moving on anyway.

But the solution can’t be to ignore what I’ve learned, can it?

So far in this essay, I’ve underappreciated my writing skills. I’ve portrayed them as obstacles to creation, as though learning too much taints your ability to create and it’s better to be stay stupid.

Of course, that’s wrong. Knowing how to write, paint, draw, code (or whatever else you do) well is crucial. And for every Edward Chisholm or Anthony Bourdain, there’s a Bill Buford or Ian McEwan, whose backgrounds could not be more expected for successful writers.

The decade-ish that I’ve been writing I’ve got to thank that I no longer have the feeling of the Taste Gap:

I know that given enough time, I will produce something that’s up to my very high standards. I’m proud of that.

But I also realize that not everything I produce will be the best thing I’ve ever made. Plus, sometimes when I thought I’d made some of my best work, nobody cared about it.

This brings me to a conclusion.

A first draft is only producing the clay you’re about to shape. The best thing I can do is to dump whatever comes to mind. Nobody cares whether or not it fits my preconceptions of good writing™. In freely writing down anything, it reliably surfaces thoughts I didn’t even know I had. Some neural connections can only happen when the mind is uninhibited.

You might cut 70% of it. I certainly did for this essay.

Once you’re working with something the editing process should surface the more discerning mind, the one who knows how to construct a rhythmically pleasant sentence. Who chooses discerning over judgmental because it’s a tad more accurate.

This is not a new insight. And if all I needed was this basic piece of advice (basically “Write drunk, edit sober”), why write a whole essay?

I guess the deeper point is that with growing knowledge, more refined tastes and higher standards to aspire to, I lost a certain levity I used to have with writing. A sense of “I want to write about that” and then do it, without thinking too much of whether it’ll win a Pulitzer or go viral or become the foundation of a Substack that could power the rest of my career.

Maybe working in marketing corrupted this. But I want to re-cultivate that sense of lightness, where the intent of writing is to make something. Not to attach my identity, my professional future or anything else to writing something.

It’s usually this type of writing that I enjoy reading the most, anyway. So what not enjoy writing it, too?