The trajectory of a storm, the evolution of stock prices, the spread of disease — mathematicians can describe any phenomenon that changes in time or space using what are known as partial differential equations. But there’s a problem: These “PDEs” are often so complicated that it’s impossible to solve them directly.

Mathematicians instead rely on a clever workaround. They might not know how to compute the exact solution to a given equation, but they can try to show that this solution must be “regular,” or well-behaved in a certain sense — that its values won’t suddenly jump in a physically impossible way, for instance. If a solution is regular, mathematicians can use a variety of tools to approximate it, gaining a better understanding of the phenomenon they want to study.

But many of the PDEs that describe realistic situations have remained out of reach. Mathematicians haven’t been able to show that their solutions are regular. In particular, some of these out-of-reach equations belong to a special class of PDEs that researchers spent a century developing a theory of — a theory that no one could get to work for this one subclass. They’d hit a wall.

Now, two Italian mathematicians have finally broken through, extending the theory to cover those messier PDEs. Their paper, published last summer, marks the culmination of an ambitious project that, for the first time, will allow scientists to describe real-life phenomena that have long defied mathematical analysis.

Naughty or Nice

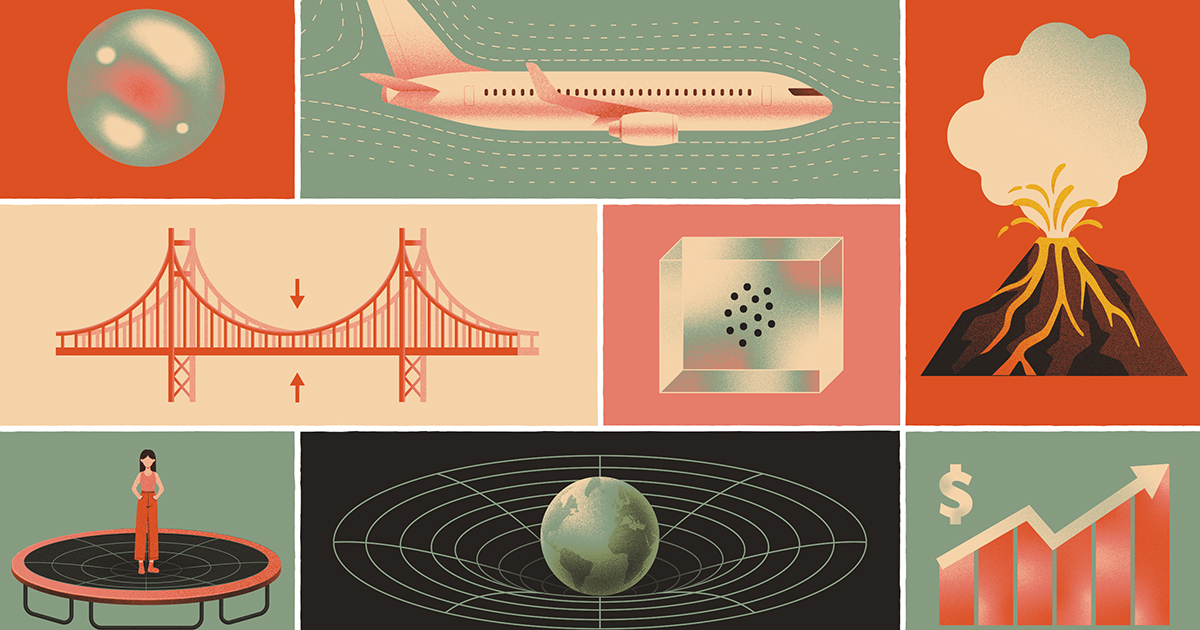

During a volcanic eruption, a scorching, chaotic river of lava flows over the ground. But after hours or days (or perhaps even longer), it cools enough to enter a state of equilibrium. Its temperature is no longer changing from moment to moment, although it still varies from place to place across the vast expanse of space the lava covers.

Mathematicians describe situations like this using what are called elliptic PDEs. These equations represent phenomena that vary across space but not time, such as the pressure of water flowing through rock, the distribution of stress on a bridge, or the diffusion of nutrients in a tumor.

But solutions to elliptic PDEs are complicated. The solution to the lava PDE, for instance, describes its temperature at every point, given some initial conditions. It depends on a lot of interacting variables.

Researchers want to approximate such a solution even when it’s impossible to write it down. But the methods they use only work well if the solution is regular — meaning that it doesn’t have any sudden jumps or kinks. (There won’t be sharp spikes in the lava’s temperature from place to place.) “If something goes wrong, it’s probably because of the [lack of] regularity,” said Makson Santos of the University of Lisbon.

In the 1930s, the Polish mathematician Juliusz Schauder sought to establish the minimal conditions an elliptic PDE must satisfy to guarantee that its solutions will be regular. He showed that in many cases, all you have to prove is that the rules baked into the equation — such as the rule for how quickly heat will spread in lava — do not change too abruptly from point to point.

In the decades since Schauder’s proof, mathematicians have shown that this condition is enough to ensure that any PDE that describes a nice, “uniform” material has regular solutions. In such a material, there’s a limit on how extreme the underlying rules can get. For example, if you assume your lava is uniform, heat will always flow within certain speed limits, never too quickly or slowly.

But lava is actually a diverse mix of molten rock, dissolved gases, and crystals. In such a nonuniform material, you can’t control the extremes, and you might get more drastic differences in how quickly heat can spread, depending on your location: Some regions in the lava might conduct heat extremely well, and others extremely poorly. In this case, you’ll use a “nonuniformly elliptic” PDE to describe the situation.

For decades, no one could prove that Schauder’s theory held for this kind of PDE.

Unfortunately, “the real world is nonuniformly elliptic,” said Giuseppe Mingione, a mathematician at the University of Parma in Italy. That meant mathematicians were stuck. Mingione wanted to understand why.

Time Machine

In August 2000, Mingione — 28 years old and fresh off his Ph.D. — found himself in a dilapidated old resort in Russia, attending a conference on differential equations. One evening, with nothing better to do, he started reading papers by Vasiliĭ Vasil’evich Zhikov, a mathematician he’d met on the trip, and he realized that nonuniformly elliptic PDEs that seem well behaved can have irregular solutions even when they satisfy the condition Schauder had identified. Schauder’s theory wasn’t simply harder to prove in the nonuniform case. It needed an update.