This week, we’re looking at scientific breakthroughs, the women who dream of chickens, and Cairo’s anarchic streets.

THE DISCOURSE

-

The Washington Post is gutted: After weeks of rumors, the Washington Post laid off over a third of its workforce this week. Every corner of the newsroom was affected, but international, sports, and books coverage were among the most severely impacted. It’s a dark day for journalism, but there is one silver lining: Ron Charles, Geoffrey Fowler, Azi Paybarah, and Chris Richards have all started Substacks since the layoffs.

-

The social network that’s (intentionally) full of bots: “AI agents have been gathering online by the thousands over the past week, debating their existence, attempting to date each other, building their own religion, concocting crypto schemes, and spewing gibberish,” Alex Kantrowitz writes. This is all happening on Moltbook, a Reddit-like social network specifically for AI agents. For some, the resulting forums are eerie glimpses at self-realized artificial intelligence; for others, including Sam Kriss, they’re an example of “what you’d expect to see if you told an LLM to write a post about being an LLM, on a forum for LLMs.” As Scott Alexander summarizes, it’s really in the eye of the beholder: “As with so much else about AI, it straddles the line between ‘AIs imitating a social network’ and ‘AIs actually having a social network’ in the most confusing way possible—a perfectly bent mirror where everyone can see what they want.”

-

Big week for sports fans: With the Winter Olympics and the Super Bowl kicking off this weekend, the sports fan’s cup runneth over. Heather Cocks & Jessica Morgan of Drinks with Broads opened up their Olympics coverage with a discussion of one of the weirder Olympics injection scandals in recent years. Meanwhile, Joe Pompliano dives into the bananas list of demands the NFL places on stadiums hoping to host the Super Bowl.

SCIENCE

We often hear about the technological innovations those born at the beginning of the 20th century lived through. In this post, Hilarius Bookbinder considers the intellectual breakthroughs of the same time period.

—Hilarius Bookbinder in Scriptorium Philosophia

I think a lot of the epistemological troubles of modernity (fake news, bad echo chambers, conspiracy theories, collapse in expert trust) can be explained by the fact that as a species we have learned so much over such a short span of time that our collective knowledge is like a thin crust of ice on the deep sea of ancestral folk wisdom. It takes very little to break through that surface and find ourselves back in the roiling waters of fables, myths, superstitions, auguries, and divination.

My grandfather was born in 1901. He once said that he thought he lived during the greatest time in history: born during horse-and-buggy days, he lived to see a man on the moon. Obviously, the technological inventions since 1901 have been staggering, but I want to look at knowledge, what we as a species have learned since then.

When Granddad was born, no one knew any of the following things. Either no one had any idea they were true or they were wacky ideas promoted strictly by lunatic visionaries. Now they are all common knowledge among educated people.

[…]

Black holes and wormholes. These darlings of sci-fi movies weren’t even a twinkle in anyone’s eye back in 1901. They are both predictions from the general theory of relativity (1915), and there wasn’t experimental confirmation of black holes until the 1970s. Wormholes are still theoretical.

The existence of galaxies. Here’s a good one. In 1901 nobody had any idea that there were other galaxies. There was the Milky Way and that was that. Sure, astronomers could see fuzzy nebulae in their telescopes, but figured they were either gas clouds or some other weird thing inside the Milky Way. It wasn’t until the 1920s (Hubble again) that we learned the truth: our galaxy with its 100 billion stars is merely a grain of sand on a vast beach. It was just a decade ago that we arrived at the current estimate of 1-2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe.

Quantum physics. Knowledge of the very tiny was itself very tiny in 1901. We knew there were atoms and electrons, but that’s it. No one knew about protons, neutrons, the nucleus, or how atoms were put together. Nuclear fission and fusion were unknown (so nobody understood why the sun was hot, or how it was powered). Splitting an atom was unheard of, much less the idea of a chain reaction. The idea that light is made of photons was also unknown.

Plate tectonics. In 1901 everyone looked at the world map, saw how the eastern coastline of North and South America perfectly fits into the western coastline of Europe and Africa like a jigsaw puzzle and thought, “huh, what a coincidence!” In 1912 Alfred Wegener suggested maybe the continents drift around the surface of the globe, a suggestion that was met with peals of laughter. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the evidence was in, and plate tectonics became settled science, explaining volcanoes, earthquakes, and how mountains arise.

Birds are dinosaurs. Thomas Huxley’s wild avian speculation in the 19th century was quickly shelved in favor of “dinos were cold-blooded, slow-moving reptiles.” It wasn’t until the 1990s (!) that it was conclusively established that there had been feathered non-avian dinosaurs, that feathers evolved before flight, and that modern birds aren’t descended from dinosaurs, but are in fact the only surviving lineage of theropod dinosaurs.

Blood types. Doctors had tried blood transfusions since the 17th century, but the results ranged from mixed to disastrous. The reason was that nobody knew about blood types, and how you can’t just mix ’n’ match. That wasn’t discovered until 1901-1902. Decades later we discovered anticoagulants (allowing blood to be stored) and the Rh factor (whether your blood type is + or -).

COLLAGE

ATHLETICS

Paul S., a climber catastrophically injured in a fall, reflects on Alex Honnold’s latest free solo and the ethics of climbing without protection.

These days I consume zero climbing media. I haven’t done since the day I woke up in hospital.

Whereas I once refreshed UKClimbing 40 times a day, obsessively consumed climbing videos on YouTube, devoured the mountain classics of literature, and leafed through my sizable library of guidebooks planning future adventures, I now pretend that when climbing ceased to exist for me, it ceased to exist for everybody.

It is still the only way that I can cope. Whereas some people who are catastrophically injured through sport still take joy in watching others participate, for me it’s too painful. I cut myself off, and never looked back. Hence I’ve no idea if Adam Ondra is still the only person to have climbed 9c, or if that even remains the highest sport grade. Same goes for E12, for Burden of Dreams. I couldn’t even guess who won the men’s gold in 2024, though I’m going to assume that Janja won the women’s.

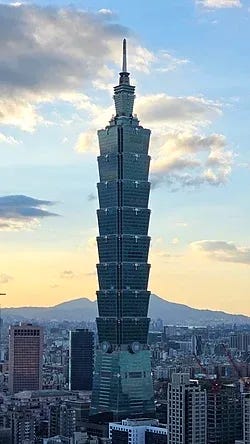

But even I heard about Alex Honnold climbing some building in Taiwan.

Before going any further, let’s get one piece of terminology straight. Honnold’s “achievement” (scare quotes to be explained in a moment) last week was not simply that he free climbed Taipei 101, but that he free soloed it. The distinction is important. Free climbing means ascending something without the use of devices to assist (“aid”) the physical moves themselves. However, assistive devices can be used whilst free climbing to prevent injury or death, should a climber’s un-aided physical moves come up short and they fall. (Think: harnesses, ropes, karabiners, et cetera.) By contrast, free soloing is free climbing, but without any of the assistive devices used to (in theory) prevent death if the climber should fall. In essence, free soloing reduces the margin of error to zero. If you fall, you die.

I free climbed literally thousands of routes before my accident. On a dozen or so occasions, I free soloed them.

A few people have cautiously asked me what I think of Honnold’s latest. My answer has generally been: “how the fuck am I the one in a wheelchair, and not him?” But there’s more to it than that.

As I don’t consume climbing media anymore, I don’t know what the general consensus is in the climbing scene regarding his latest spectacle. But I’d wager that most climbers had the same response as me: a rolling of the eyes.

This might seem weird. Isn’t free soloing a 500m building an impressive athletic and psychological achievement, and shouldn’t climbers respect that more than anybody? Putting aside for now (we will get there in a minute) furious debates between climbers about the acceptability of free soloing in general, my guess is that even people who free solo won’t have been positively disposed.

First, because although what Honnold did will look impressive to non-climbers, those who climb will know that it was nowhere near as hard (to him) as it looks. The now widely circulated footage of making what appear to be difficult moves on the tower are in fact not so for somebody with advanced climbing skills, which he undoubtedly possesses. Those moves are far below Honnold’s technical and physical limits. If you don’t climb, this will be hard to believe, but take it from me: for somebody of his ability, climbing Taipei 101 is about as difficult as going up a ladder. Sure, it’s not a good idea to fall off a 500m ladder. If you do, you will die. But if you don’t, you won’t.

And yes, it takes good mental composure to not panic, to be able to commit to something like that from start to finish. But this is hardly Honnold’s first rodeo. He has spent years free soloing, and thus has trained his amygdala such that a panic response is simply not going to happen to him, even at 400m off the ground. If you’ve never climbed a ladder before, then going even 20m up a ladder will likely cause you to quake with fear and be desperate to come down. But if you climb a thousand 20m ladders over the next 20 years, you’re not going to find it remotely difficult to safely climb another one tomorrow. (And trust me, once you are comfortable at 20m, you’re comfortable at 500.)

Which is not to say that none of Honnold’s achievements as a free soloist are impressive. Quite the contrary. He has previously pushed the limits of free soloing far beyond what was thought possible, and in a way every climber respects (even if only begrudgingly). When he soloed El Capitan in Yosemite, this was a moment of human accomplishment on a par with being the first to run 100m in under 9.8 seconds—except with the added twist of failure meaning certain death. The film Free Solo is genuinely worth watching, both as a piece of documentary evidence for what he accomplished as well as an interesting insight into the rare psychology of the committed soloist, someone pushing the limits beyond what anybody thought the envelope would allow.

But that itself is now part of the problem. Taipei 101 is not El Cap. There is no beauty, in terms of the movement of a human body on rock, to be found in the capital of Taiwan. It is one thing to add potentially the most storied chapter to the grand history of Yosemite climbing, quite another to do a Netflix special. Not even Honnold is going to pretend—the soloist’s oldest defence—that there is a deep spiritual communion to be found in mechanically repeating moves on concrete blocks, filmed by a dozen cameras, as part of a multimillion-dollar media operation.

And capped off by taking a selfie at the top.

I mean, he’s not even the first person to free solo tall buildings. Alain Robert has been doing it for years, usually illegally, and without making money from it. Where is his Netflix cash-in?

In other words, my predominant response to Alex Honnold’s latest media acclaim is that I’m still a punk rock kid at heart: fucking sell-out.

WINTER OLYMPICS

TRENDS

Lisa Kholostenko examines the strange lure that raising chickens seems to hold over millennial women.

—Lisa Kholostenko in Empty Calories

I am a Millennial white woman and yet, I say this bravely, I do not want chickens.

I want many things. A calm nervous system. An abundant bank account. Taylor Russell’s coats. But chickens? No.

Many of my friends want them. Many Millennial white women want them. Women I know personally. Women I know spiritually. Kristin Cavallari has chickens. Hilary Duff has chickens. Amanda Seyfried? Chickens. Women with blowouts and impeccable contouring are waking up at dawn to collect eggs before their Pilates classes, like they’re in a Perry-free version of Big Little Lies, executive produced by Goop.

Why? What are the chickens saying? Why are the chickens here? Is this about eggs, or something else? A lifestyle thesis disguised as poultry? Because no one actually wants to care for an animal that screams, attacks you with its beak, and can be taken out by a stiff breeze.

Perhaps chickens feel less like a pet and more like an announcement: I HAVE SPACE NOW. Physical space. Emotional space. Acreage. A mudroom.

Chickens imply land. You don’t get chickens unless you’ve graduated from “apartment person” to “someone who casually says ‘the property.’” You don’t get chickens unless someone in your home knows their way around a hammer, a latch and a ramp (for the dramatic chickens). You don’t get chickens unless you are committing to a life of many omelettes.

The aesthetic argument, of course, is airtight. Chickens pair beautifully with a DÔEN dress. You can imagine yourself drifting through your yard at golden hour, hem grazing calf, hair in a loose, morally superior braid, whispering affirmations to a Rhode Island Red. The fantasy is powerful: no screens. Just you and your flock, living off the land. You’re baking sourdough while your chicken friend looks on approvingly: ah yes, good, she thinks, this will go nicely with a breakfast sandwich. You’ve taken a guitar. Not because you play, but because it makes sense. There’s shelving with a lot of bobbins and even more homemade jams. The bobbins and jams are as abundant as the domestic fowl. Does this sound like something you’d be interested in? Need I bring up shiplap?

Never mind that chicken caretaking is, by all accounts, bureaucratic labor involving mites, fencing disputes, and the devastation of discovering that something called a “hawk” exists. The fantasy does not include any of that. The fantasy includes speckled eggs in a ceramic bowl. Overalls.

So I decided to investigate.

Again, not because I want chickens but because the chickens want me. They’re circling. They’re symbolic. A feathered milestone. And I thought it was my duty, as a woman still emotionally renting and more interested in a lymphatic drainage massage than livestock, to look this thing in the eye and ask the only question that matters: what is this all about?

DREAMLAND

TRAVEL

Christian Näthler on the life-affirming chaos of Cairo’s traffic.

There’s that gabe k-s quote that goes, “There must be something like the opposite of suicide, whereby a person radically and abruptly decides to start living.”

By that measure, the opposite of suicide is to spend a few days walking and driving the streets of Cairo.

⁂

True, it can feel like self-murder. Cairo has more than 23 million people and no traffic lights. Getting anywhere demands submitting to an unruly accumulation of motion and believing unwaveringly in the ancient concept of going with the flow. It’s very somatic. It made me feel bodily, that I had a presence. It gave shape to me insofar as I became a construction of a thing competing for space with other constructed things. It also made me feel totally irrelevant and trivial. There was a unique spectrum within me and across which I felt myself being thrust toward the extreme ends of: flesh-based conception on one side and disembodiment on the other.

⁂

And where was my mind? Speculating about what it would be like for a bus to run me over and make me flat and, because the vehicles are so one after the other, to squash me several times before anyone stopped, until what was left of me could be used to paint walls, until there was only a granular paste a passerby might skid on and pull their groin.

⁂

It’s no news by now that Cairo’s congestion rivals the world’s great clusterfucks—Delhi, Lagos, Manila. Without a coherent authority, everyone does what they want. I like the self-regulating anarchy. I find it relaxing, even when it feels like it could crush me at any second. What stresses me out is the world of policies and litigation.

Such interconnectedness means individual choices matter. A heedless insistence on one’s own priority disrupts the harmony of the whole. And so there’s a real sense of society in the ceaseless tightening and loosening of the knot, the communal negotiation of space. It can be ruthless, but there are small mercies everywhere. Now and then, a hand lifts briefly from a steering wheel to signal that you may merge.

⁂

As for “living like a local,” infused with exhaust and coated in road smut is perhaps the most authentic way to be in Cairo, an experience shared by almost everyone who lives here. You get used to the scratch in your throat.

⁂

An inventory of things in transit, noted over 13 minutes at Ramses Square:

Cars, taxis, minibuses, public buses, tourist buses, delivery vans, pickup trucks, dump trucks, cement mixers, fuel tankers, water trucks, garbage trucks, tow trucks, road rollers, cranes in transit, police cars, police vans, armored police vehicles, military trucks, ambulances, fire engines, motorcycles, scooters, tuk-tuks, motorized rickshaws, bicycles, handcarts, pushcarts, produce carts, wheelbarrows, mule carts, pedestrians, street vendors on foot, men carrying trays, children weaving through traffic, mechanics rolling tires, people pushing stalled cars, refrigerators on carts, mattresses strapped to bicycles, gas canisters on trolleys, rolling crates, rolling plastic barrels, rollerbladers, dogs, stray shopping carts.

⁂

It really is another world. Of course we all know the “we” and “us” of contemporary culture writing refers to a rather narrow Western milieu, but the boundless vastness of humanity to be observed on Cairo’s streets makes it seem like that whole referred-to audience could fit into a single backyard in Williamsburg.

Flaubert wrote, “Travel makes one modest. You see what a tiny place you occupy in the world.” But it was more like I saw what a tiny world occupied me.

Art & Photography: Hurrikan Press, Stella Kalaw, Jörgen Löwenfeldt

Video & Audio: Olivia Rafferty ✨

Writing: Hilarius Bookbinder, Paul S, Lisa Kholostenko, Christian Näthler

Bookmarked by Reese’s Book Club has launched. Reese Witherspoon’s first post describes it as “a cozy corner of the internet where we can actually talk about the books we love and pick up even more reads along the way.”

Actress and model Meg Stalter has joined Substack, kicking things off with a personal essay about her relationship to religion, God, and morality.

The Washington Post’s former book critic Ron Charles has turned Substack into his new home, where he “intend[s] to keep nattering on about books, authors, and our imperiled literary culture.”

Comedian and actor Jeff Hiller has joined Substack to “try to lower your cortisol and bring a little bit of joy to the world or at least your inbox.”

Harvard Law professor and author Noah Feldman has joined Substack, where he’ll be sharing “what you might call actionable wisdom: thoughts that you can put to use in your own life, that you can discuss with the people who matter to you, and that you can translate into feeling more connected, balanced, and engaged in your own life.”

Inspired by the writers and creators featured in the Weekender? Starting your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.