Last week I started using some of the newer coding tools properly. Not in a careful, experimental way, but properly — for three days on rqlite. Claude Code. Copilot CLI. Tools I had yet to fully integrate into how I write software.

Last week I started using some of the newer coding tools properly. Not in a careful, experimental way, but properly — for three days on rqlite. Claude Code. Copilot CLI. Tools I had yet to fully integrate into how I write software.

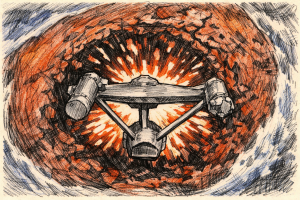

If you know The Doomsday Machine — the original Star Trek episode where Kirk finds Commodore Decker alone on his wrecked ship — there is a moment that has stayed with me. Kirk asks Decker where his crew is. Decker says they are on the third planet. Kirk tells him there is no third planet. Decker, almost catatonic, says:

“Don’t you think I know that? There was, but not anymore!”

That is roughly how I now feel about the moat of my open-source code.

What happened

rqlite is an open-source distributed database. I work in the code base almost every week. It is my main project outside of my day job. After all, I created it, and I care about it in the way I think most open-source developers care about the things they build. Not for money — I have a day job — but out of pride, and a drive to make it as good as it can be. I suspect anyone who maintains a serious open-source project knows exactly what I mean.

But knowing what should change and actually doing it are different things. rqlite has a long backlog of features and refactors. I understood them all perfectly well. I knew what each change would look like, roughly how long it would take, and why it mattered. I had not done them because the work was tedious. The return did not justify the hours. So they sat.

Last week, with these tools, I started pulling items off that backlog. Features I had been deferring — not because I did not understand the code, but because the effort felt disproportionate — suddenly took a fraction of the time. Features I had wanted to ship for years were within reach. The work felt almost light.

That was the first realization. I could do things I had always wanted to do but had judged not worth the cost.

The second realization arrived soon afterwards, and it was less pleasant.

The gravity of existing code

For a long time, rqlite’s real advantage was not that its source code was secret. It has an MIT license. Anyone can read it.

The advantage was that it existed.

A working, mature distributed database, already handling consensus, already embedding SQLite, already in production. If you wanted a new feature in a SQLite-based distributed database, the path of least resistance was to build it in rqlite, or fork rqlite, or contribute to rqlite. The code base had gravity. Starting from scratch meant reproducing years of work — the architecture, the edge cases, the failure modes, the lessons learned. Nobody was going to do that just to add one feature.

That gravity was the moat. Not secrecy. Not even the specific design ideas, though those mattered. The moat was the sheer accumulated investment embodied in a working system. The fact that all that code was already written and already worked.

What changed

These tools do not just make it easier to change rqlite. They make it easier to build something new.

The cost of getting a new system to the point where rqlite already stands has dropped sharply. Not to zero — distributed systems are still hard, and production experience still matters. But the gap between a mature code base and a fresh start is no longer what it was. The advantage of already existing, of having the code written and the edge cases handled, counts for less than it did a year ago.

That is what unsettled me. The threat was never that someone would fork rqlite and add a feature. The threat is that someone will build their own distributed database and add that feature faster than I would have thought possible. The pre-existence of a well-structured codebase — all that accumulated work — simply matters less now.

Both directions

But this cuts both ways.

The same tools that lower the barrier for others have cleared my own backlog. Features that sat for years because the effort was disproportionate are now shipping. rqlite is improving faster than it has in a long time, and the work is genuinely enjoyable.

The comfort is gone, though. Even open-source projects have competitors, and their maintainers have access to the same tools I do. If a feature people want sits on my list too long, someone else will ship it in their own system. That pressure focuses the mind.

Years ago I wrote that the real value in open source was never the code but the team behind it, and that remains true. But what has changed is how quickly someone else can close the gap.

The source code was the moat. But not anymore.