pycparser is my most widely used open

source project (with ~20M daily downloads from PyPI ). It’s a pure-Python

parser for the C programming language, producing ASTs inspired by Python’s

own. Until very recently, it’s

been using PLY: Python Lex-Yacc for

the core parsing.

In this post, I’ll describe how I collaborated with an LLM coding agent (Codex)

to help me rewrite pycparser to use a hand-written recursive-descent parser and

remove the dependency on PLY. This has been an interesting experience and the

post contains lots of information and is therefore quite long; if you’re just

interested in the final result, check out the latest code of pycparser – the

main branch already has the new implementation.

The issues with the existing parser implementation

While pycparser has been working well overall, there were a number of nagging

issues that persisted over years.

Parsing strategy: YACC vs. hand-written recursive descent

I began working on pycparser in 2008, and back then using a YACC-based approach

for parsing a whole language like C seemed like a no-brainer to me. Isn’t this

what everyone does when writing a serious parser? Besides, the K&R2 book

famously carries the entire grammar of the C99 language in an appendix – so it

seemed like a simple matter of translating that to PLY-yacc syntax.

And indeed, it wasn’t too hard, though there definitely were some complications

in building the ASTs for declarations (C’s gnarliest part).

Shortly after completing pycparser, I got more and more interested in compilation

and started learning about the different kinds of parsers more seriously. Over

time, I grew convinced that recursive descent is the way to

go – producing parsers that are easier to understand and maintain (and are often

faster!).

It all ties in to the benefits of dependencies in software projects as a

function of effort.

Using parser generators is a heavy conceptual dependency: it’s really nice

when you have to churn out many parsers for small languages. But when you have

to maintain a single, very complex parser, as part of a large project – the

benefits quickly dissipate and you’re left with a substantial dependency that

you constantly grapple with.

The other issue with dependencies

And then there are the usual problems with dependencies; dependencies get

abandoned, and they may also develop security issues. Sometimes, both of these

become true.

Many years ago, pycparser forked and started vendoring its own version of PLY.

This was part of transitioning pycparser to a dual Python 2/3 code base when PLY

was slower to adapt. I believe this was the right decision, since PLY “just

worked” and I didn’t have to deal with active (and very tedious in the Python

ecosystem, where packaging tools are replaced faster than dirty socks)

dependency management.

A couple of weeks ago this issue

was opened for pycparser. It turns out the some old PLY code triggers security

checks used by some Linux distributions; while this code was fixed in a later

commit of PLY, PLY itself was apparently abandoned and archived in late 2025.

And guess what? That happened in the middle of a large rewrite of the package,

so re-vendoring the pre-archiving commit seemed like a risky proposition.

On the issue it was suggested that “hopefully the dependent packages move on to

a non-abandoned parser or implement their own”; I originally laughed this idea

off, but then it got me thinking… which is what this post is all about.

Growing complexity of parsing a messy language

The original K&R2 grammar for C99 had – famously – a single shift-reduce

conflict having to do with dangling elses belonging to the most recent

if statement. And indeed, other than the famous lexer hack

used to deal with C’s type name / ID ambiguity,

pycparser only had this single shift-reduce conflict.

But things got more complicated. Over the years, features were added that

weren’t strictly in the standard but were supported by all the industrial

compilers. The more advanced C11 and C23 standards weren’t beholden to the

promises of conflict-free YACC parsing (since almost no industrial-strength

compilers use YACC at this point), so all caution went out of the window.

The latest (PLY-based) release of pycparser has many reduce-reduce conflicts

; these are a severe maintenance hazard because it means the parsing rules

essentially have to be tie-broken by order of appearance in the code. This is

very brittle; pycparser has only managed to maintain its stability and quality

through its comprehensive test suite. Over time, it became harder and harder to

extend, because YACC parsing rules have all kinds of spooky-action-at-a-distance

effects. The straw that broke the camel’s back was this PR which again proposed to

increase the number of reduce-reduce conflicts .

This – again – prompted me to think “what if I just dump YACC and switch to

a hand-written recursive descent parser”, and here we are.

The mental roadblock

None of the challenges described above are new; I’ve been pondering them for

many years now, and yet biting the bullet and rewriting the parser didn’t feel

like something I’d like to get into. By my private estimates it’d take at least

a week of deep heads-down work to port the gritty 2000 lines of YACC grammar

rules to a recursive descent parser . Moreover, it wouldn’t be a

particularly fun project either – I didn’t feel like I’d learn much new and

my interests have shifted away from this project. In short, the Potential well was just too deep.

Why would this even work? Tests

I’ve definitely noticed the improvement in capabilities of LLM coding

agents in the past few months, and many reputable people online rave about using

them for increasingly larger projects. That said, would an LLM agent really be

able to accomplish such a complex project on its own? This isn’t just a toy,

it’s thousands of lines of dense parsing code.

What gave me hope is the concept of conformance suites mentioned by

Simon Willison.

Agents seem to do well when there’s a very clear and rigid

goal function – such as a large, high-coverage conformance test suite.

And pycparser has an very extensive one.

Over 2500 lines of test code parsing various C snippets to ASTs with expected

results, grown over a decade and a half of real issues and bugs reported by

users.

I figured the LLM can either succeed or fail and throw its hands up in despair,

but it’s quite unlikely to produce a wrong port that would still pass all

the tests. So I set it to run.

The initial port

I fired up Codex in pycparser’s repository, and wrote this prompt just to

make sure it understands me and can run the tests:

This repository implements a Python parser producing an AST. It has a very

extensive test suite; can you first verify you successfully run all the tests?

(with python3 -m unittest discover, from the root dir)

Codex figured it out (I gave it the exact command, after all!); my next

prompt was the real thing :

pycparser uses the PLY library for its lexer and parser, and its own AST

package for the ASTs created by the parser. I want to explore replacing the

Parser component (leaving the Lexer alone for now) with a hand written

recursive descent parser that will pass all the same tests. Can you try that?

Here Codex went to work and churned for over an hour. Having never

observed an agent work for nearly this long, I kind of assumed it went off

the rails and will fail sooner or later. So I was rather surprised and skeptical

when it eventually came back with:

Replaced the PLY parse path with a handwritten recursive‑descent parser while

keeping the existing lexer and AST helpers intact; CParser now points to the

new RD implementation, with the old PLY version preserved as PLYCParser in

pycparser/c_parser.py. The RD parser includes a token stream, declarator/type

parsing, expression precedence handling, pragmas, and statement parsing to

match the previous AST output and coordinate behavior.

It took me a while to poke around the code and run it until I was convinced – it

had actually done it! It wrote a new recursive descent parser with only

ancillary dependencies on PLY, and that parser passed the test suite. After a

few more prompts, we’ve removed the ancillary dependencies and made the

structure clearer. I hadn’t looked too deeply into code quality at this point,

but at least on the functional level – it succeeded. This was very impressive!

A quick note on reviews and branches

A change like the one described above is impossible to code-review as one PR in

any meaningful way; so I used a different strategy. Before embarking on this

path, I created a new branch and once Codex finished the initial rewrite, I

committed this change, knowing that I will review it in detail, piece-by-piece

later on.

Even though coding agents have their own notion of history and can “revert”

certain changes, I felt much safer relying on Git. In the worst case if all of

this goes south, I can nuke the branch and it’s as if nothing ever happened.

I was determined to only merge this branch onto main once I was fully

satisfied with the code. In what follows, I had to git reset several times

when I didn’t like the direction in which Codex was going. In hindsight, doing

this work in a branch was absolutely the right choice.

The long tail of goofs

Once I’ve sufficiently convinced myself that the new parser is actually working,

I used Codex to similarly rewrite the lexer and get rid of the PLY dependency

entirely, deleting it from the repository. Then, I started looking more deeply

into code quality – reading the code created by Codex and trying to wrap my head

around it.

And – oh my – this was quite the journey. Much has been written about the code

produced by agents, and much of it seems to be true. Maybe it’s a setting I’m

missing (I’m not using my own custom AGENTS.md yet, for instance), but

Codex seems to be that eager programmer that wants to get from A to B whatever

the cost. Readability, minimalism and code clarity are very much secondary

goals.

Using raise...except for control flow? Yep. Abusing Python’s weak typing

(like having None, false and other values all mean different things

for a given variable)? For sure. Spreading the logic of a complex function

all over the place instead of putting all the key parts in a single switch

statement? You bet.

Moreover, the agent is hilariously lazy. More than once I had to convince it

to do something it initially said is impossible, and even insisted again in

follow-up messages. The anthropomorphization here is mildly concerning, to be

honest. I could never imagine I would be writing something like the following to

a computer, and yet – here we are: “Remember how we moved X to Y before? You

can do it again for Z, definitely. Just try”.

My process was to see how I can instruct Codex to fix things, and intervene

myself (by rewriting code) as little as possible. I’ve mostly succeeded in

this, and did maybe 20% of the work myself.

My branch grew dozens of commits, falling into roughly these categories:

- The code in X is too complex; why can’t we do Y instead?

- The use of X is needlessly convoluted; change Y to Z, and T to V in all

instances. - The code in X is unclear; please add a detailed comment – with examples – to

explain what it does.

Interestingly, after doing (3), the agent was often more effective in giving

the code a “fresh look” and succeeding in either (1) or (2).

The end result

Eventually, after many hours spent in this process, I was reasonably pleased

with the code. It’s far from perfect, of course, but taking the essential

complexities into account, it’s something I could see myself maintaining (with

or without the help of an agent). I’m sure I’ll find more ways to improve it

in the future, but I have a reasonable degree of confidence that this will be

doable.

It passes all the tests, so I’ve been able to release a new version (3.00)

without major issues so far. The only issue I’ve discovered is that some of

CFFI’s tests are overly precise about the phrasing of errors reported by

pycparser; this was an easy fix.

The new parser is also faster, by about 30% based on my benchmarks! This is

typical of recursive descent when compared with YACC-generated parsers, in my

experience. After reviewing the initial rewrite of the lexer, I’ve spent a while

instructing Codex on how to make it faster, and it worked reasonably well.

Followup – static typing

While working on this, it became quite obvious that static typing would make the

process easier. LLM coding agents really benefit from closed loops with strict

guardrails (e.g. a test suite to pass), and type-annotations act as such.

For example, had pycparser already been type annotated, Codex would probably not

have overloaded values to multiple types (like None vs. False vs.

others).

In a followup, I asked Codex to type-annotate pycparser (running checks using

ty), and this was also a back-and-forth because the process exposed some

issues that needed to be refactored. Time will tell, but hopefully it will make

further changes in the project simpler for the agent.

Based on this experience, I’d bet that coding agents will be somewhat more

effective in strongly typed languages like Go, TypeScript and especially Rust.

Conclusions

Overall, this project has been a really good experience, and I’m impressed with

what modern LLM coding agents can do! While there’s no reason to expect that

progress in this domain will stop, even if it does – these are already very

useful tools that can significantly improve programmer productivity.

Could I have done this myself, without an agent’s help? Sure. But it would have

taken me much longer, assuming that I could even muster the will and

concentration to engage in this project. I estimate it would take me at least

a week of full-time work (so 30-40 hours) spread over who knows how long to

accomplish. With Codex, I put in an order of magnitude less work into this

(around 4-5 hours, I’d estimate) and I’m happy with the result.

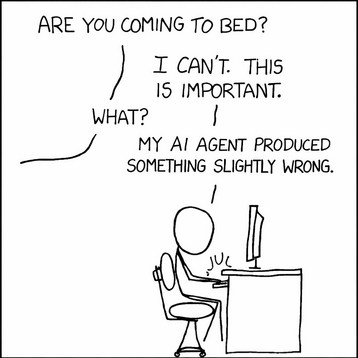

It was also fun. At least in one sense, my professional life can be described

as the pursuit of focus, deep work and flow. It’s not easy for me to get into

this state, but when I do I’m highly productive and find it very enjoyable.

Agents really help me here. When I know I need to write some code and it’s

hard to get started, asking an agent to write a prototype is a great catalyst

for my motivation. Hence the meme at the beginning of the post.

Does code quality even matter?

One can’t avoid a nagging question – does the quality of the code produced

by agents even matter? Clearly, the agents themselves can understand it (if not

today’s agent, then at least next year’s). Why worry about future

maintainability if the agent can maintain it? In other words, does it make sense

to just go full vibe-coding?

This is a fair question, and one I don’t have an answer to. Right now, for

projects I maintain and stand behind, it seems obvious to me that the code

should be fully understandable and accepted by me, and the agent is just a tool

helping me get to that state more efficiently. It’s hard to say what the future

holds here; it’s going to interesting, for sure.