Brands made you feel emotions, but they are not your savior.

This newsletter is sponsored by our friends at Tracksuit, the always-on, affordable brand tracking dashboard. Now tracking 25 markets (and growing), giving you consistent brand health data everywhere you operate.

Before you go further, Attention is like money – you can waste it or invest it. If you invest it in my paid newsletter, you’ll get dividends for years.

While I am not a fan of the strategies that claim brands will become the new media, build third spaces, and so on, I do want to entertain those ideas today. We are moving toward a system that may enable all those not-really-strategies to thrive. But why?

Spotify launching physical books, Polymarket launching a free grocery pop-up. Netflix shortening the theatrical window, while YouTubers move into cinema. These are both red and green flags.

There are two strategies at play. The first is that brands like Spotify fundamentally change consumer behavior around a product, such as music or reading. Then enshittification happens, and people begin to seek a new experience. For a while, companies exploit this cycle by offering that new experience in snack-sized bites to keep people hooked and engaged within the existing system. It is what Meta tried with Instagram. They copied features to retain users, but it was clear to many that something had to change. That change was TikTok. Now everyone, including TikTok, is repeating the pattern, delivering micro dramas and pushing short videos onto television screens. But cultural shifts cannot be contained forever, and another platform is already forming at the edge.

The same story is unfolding with brands. They are being told to build spaces and create media to entertain people, largely by those who are more interested in sustaining the current system than repairing its long-term funding. This is the slop cycle. Marketers advise brands to do better work because attention is the new currency, and just as quickly, they recycle whatever captures it. You may get 1% better content in the market, but you also get 99% slop for free. With Netflix and Spotify, it is the same dynamic. There are good songs and films, but those platforms also slip in nonhuman artists and second screen friendly plots.

If the goal is to sustain attention and ensure survival, then yes, brands may become media brands. But the product or content will not clear the quality barrier for long.

The second strategy is the McDonald’s approach. The brand has had many product successes, such as all day breakfast and the Snack Wrap, yet both were discontinued. The brand initially discontinued the Snack Wrap, citing “operational complexity,” which essentially meant it disrupted their existing system. In short, the fast in fast food mattered more than the food itself.

This is what Netflix sees in cinema, though we rarely say it out loud. Netflix has the resources to personalize the cinema going experience. It began as a DVD delivery service, if it wanted to, it could have created a watch your movie in our Netflix theater model for its huge catalog of original content. But it did not, and the absence of that model will lead to other outcomes. Netflix is just like McDonald’s, its fast food is binge watching, and it is now also trying short form feeds to turn binge watching into doomscrolling.

Cinemas that lose business because of Netflix’s strategy may begin to experiment with more personalization. There may be greater emphasis on short films and reruns, subscription models like AMC A List could soon expand. The idea of watching social media on a big screen with friends may become normalized. All of this could reshape cinemas into more brand friendly and hangout friendly spaces.

Both strategies are rooted in a kind of systematic negligence, internal and external, designed to keep the current system alive. That is how we arrive at extreme examples. Polymarket, a gambling platform, launches a free grocery store under the language of free markets and donations. In the long term, this serves the brand image of a company extracting value from the American economy. The same applies to Kalshi, which also gave away free groceries. These companies are not trying to help anyone. They are farming attention and repositioning themselves.

So what is the answer, and what is the problem with all of this? You may have heard Mark Carney at Davos say, “Nostalgia is not a strategy.” That line lingers because it is true. Nostalgia, IP, brands becoming media companies, brands fixing third spaces, none of these are actual strategies. They are reactions to the conditions we are living through. Nostalgia is an escape. Brands producing media while traditional media weakens is a distortion. Brands creating third spaces while funding for local libraries disappears is a substitution, not a solution.

You can sell temporary emotion through this brand savior complex, but you cannot build a durable brand on it. The emotion fades, eventually people ask for an update on the project, the third space, the community you promised to build. More importantly, brands will soon face a judgment call.

The current system is reshaping consumer behavior faster than marketing can respond. It will require far more advertising dollars to undo the behavioral damage of a broken economic structure than most companies are prepared to spend. So the decision becomes simple. Are you more committed to good marketing, or to good actions that keep consumers healthy and sane?

In partnership with Tracksuit

Let me break it down like this, ladies and gentlemen, these brands are locked into million-dollar contracts, and more than 100 million people are about to tune in for Super Bowl 60. We don’t know what will happen on the field, but every timeout leads to an ad.

Tracksuit’s always-on brand tracking shows that between January 2025 and December 2025, Liquid Death’s awareness across all demographics was up three percentage points to 39%, ChatGPT’s awareness is up 13 percentage points to 74%, and Oikos’ consideration is up three percentage points to 37%. This continuous measurement is what lets us spot momentum before it becomes undeniable – and understand whether massive media moments like the Super Bowl actually move the needle on brand health.

These brands have played healthy all season, and the mass relevance they will gain from the Super Bowl will be their destiny. It’s the strategy of all big brands, Super Bowl is the play you make to optimise all of your other brand-building. The mass relevance gained from the ad makes your entire marketing spend more efficient.

As we move down, we see brands that are mainstream and legacy players, but they need to make new plays at the Super Bowl. Lay’s has been teasing their strategy, with awareness down three percentage points to 90%, they need a win. Their competitor is also down, Pringles’ awareness is down five percentage points to 85%. Having seen the ads from both brands, one is banking on storytelling, the other is all about star power, Pringles is with Sabrina Carpenter at the Super Bowl.

What this tells you is that brands, whether old or new, have a universal need to map their journeys before they head out onto the field, which means they need good data about their brands, audiences, and competitors. The Super Bowl isn’t just an advertising moment – it’s a measurable inflection point.

With continuous brand tracking, you can establish your baseline before the game, watch what shifts during the moment, and prove whether that multi-million dollar investment actually built awareness, strengthened consideration, or shifted brand perceptions. If Tracksuit can help you understand the state of Super Bowl brand sponsors, it can help your brand win the big game.

Check out Tracksuit’s always-on brand tracking dashboard

If being called performative was not enough, people are now worrying about how they sound as ordinary humans. More people are being accused of using AI to write, and even more are afraid they are beginning to sound like AI themselves. There are new studies and well researched articles on this issue, and they are not just analyzing LinkedIn posts that have always sounded robotic.

Over the summer, Kiara Stent set out on a hunt. She started scrolling through the LinkedIn posts of various people — including leaders in the marketing field and people she knows — reading some 200 posts across about 50 different profiles. What she found “made me lose a little bit of respect,” she said, especially for the people in more senior roles. About 75% of the posts, in her opinion, seemed to be generated by artificial intelligence.

In June 2025, Sarah Parker at The Verge wrote an article titled “You Sound Like ChatGPT,” and Adam Aleksic has also discussed AI speech at length, explaining how people are now avoiding certain words and sentence structures so they do not sound artificial.

There is also a growing consensus that creators who cater only to the attention economy are adapting to the way AI speaks, which in turn makes audiences more likely to engage with that content. Why would they not? Phrases like it is not about X, it is about Y function as micro dramas in written form, always leaving the reader hanging by a thread.

All of this might not have happened if the content cycle were slower. What we often miss in debates about performative behavior is that something becomes performative when people abandon it as soon as it is no longer fashionable or mainstream. Is that so different from how Millennials and Gen-X grew up? In essence, it is not. The difference is that the consumption cycle is faster, and the social pressure to keep up with changing language is constant.

That social pressure, combined with algorithmic surveillance, the content cycle, and nostalgia, has produced what we now call performative culture. We shame individuals rather than questioning the system that asks young people to consume more and remain constantly updated. Now that same system is encouraging us to censor ourselves so we do not sound like AI.

It also makes me realize that comments accusing random people of using AI are more likely to create an atmosphere of fear for the public than companies actually pushing AI-generated content. We risk getting stuck in another cycle of policing one another. In some cases that may be reasonable, but more often it distracts us from the deeper problems.

All of this hurts marketing, especially on social media, platforms are already filled with bots. I moderate two subreddits and have several posts ranking on Google. Every day I receive bot comments that not only promote a brand but also offer feedback on competitors to signal authenticity. That alone threatens the quality of social listening. The other issue is what we discussed earlier, people holding back their thoughts because of the performative nature of the internet and the ongoing flood of low quality AI content. Audience feedback that is not one to one should be treated with caution. Brands need to invest more time in creating online and offline environments where people feel comfortable speaking naturally.

Finally, I do not need to explain the political dimension. Surveillance technology is widespread, and many people feel the need to play it safe and avoid drawing attention. Platform moderation had already changed how we speak about death, politics, and mental health. This is the new age of self-censorship, where people constantly feel the need to stick to what is considered normal and to be cautious about what they post and how they speak. Anti-performative posts are often the very messages that keep people from discovering their true selves and speaking openly.

Corporate Speak → AlgoSpeak → AI Speak → What’s next?

P.S. Yes, some people deliberately provoke outrage and refuse to censor their views, but they are not the majority.

Now this is actually a strong example of what happens when a brand takes the media-first route and fails. You simply become media, and that becomes the new brand. It is what Quibi, Yahoo, BuzzFeed, and many other media first companies with weak or failed core products have done. They farm attention and sell it to advertisers and each other. KamalaHQ appears to be adapting to that same paradigm.

It is a logical move, even if it is supported by some misguided posts. The people managing KamalaHQ faced a fair share of criticism after the election and following their team’s appearances on Pod Save America. Although it is still too early to make a definitive judgment, it seems they have learned very little from publications such as COURIER, which frequently collaborates with the Democrats’ TikTok and Instagram accounts. Courier’s coverage reaches a wide variety of people, and its distribution strategy appears to be well developed. You also have shit you should care about reaching millions of Gen Zers on their social channels without relying on too much fake optimism.

The first few posts on their TikTok try to piggyback on the pre-2024 election energy, which is not relevant in any meaningful way. Dare I say, the Pepsi Super Bowl rollout with the Coca Cola polar bear feels more sincere than KamalaHQ, now known as Headquarters. First, you engage with an almost outdated trend and then create fanfare around your social team, which most people have never interacted with. I do not usually say let us leave politics aside, but in this case we can. Participating in 67 brainrot, celebrating 2016, ignoring anything currently relevant, and reducing your platform to a Gen Z-led progressive content hub is not what draws people in.

This might be a hot take, but we should move away from rollouts that explicitly announce themselves as product launches. Most of the time, they come across as boring or cringeworthy. Overall, the strategy of brands that understand the current media landscape has been to stay nonchalant on their own social channels and tease collaborations through other accounts such as Deuxmoi and Pop Crave. A subtle partnership with an influencer can hint at a product, or, if the budget allows, a staged paparazzi moment can introduce it. It is a traditional playbook, but it establishes the sense that something significant is happening.

Rollouts often exaggerate and bury the real reasons fans might care about an announcement. In a previous newsletter, I discussed the need to manufacture a reaction to signal how audiences should feel about a brand. Rollouts often push that strategy too far by being overly explicit about what audiences are supposed to feel.

Much of the current backlash might have been avoided if KamalaHQ had not opened with a direct reenactment of the “Did you miss us?” Kim K meme. Rollouts should leave room for followers to remix reactions and shape interpretations for those outside the core audience. A lack of context can sometimes help, allowing dedicated fans to explain why a launch matters. Always leave room for positive interpretation and audience conversation.

Lastly, I am not entirely upset with the new KamalaHQ. I simply hope they learn something from outlets like Wired, NowThis, COURIER , and independent creators such as Dave Jorgenson. They reference culture and generate views without attracting accusations of cringe.

Disclaimer: This is the redacted/less biased version of my original rant on Instagram. I’m self-censoring.

Fan culture is basically dead now. You can be a fan of a particular artist, but the moment you criticize them, stans will call you a hater. That is partly because stans often care more about the brand image of their favorite artist than about the music itself.

This brings me to my second point. Fans of certain artists seem more interested in the long-term brand identity they gain from being stans than in the music. More people than ever feel a lack of identity, and movements like MAGA have taken advantage of that by offering a brand people can wear and associate with.

That is what so-called stans see in some artists. They see a future in them. They see content they can create about being a fan, and an identity they can build around it. It is not a healthy culture, as it alienates the broader fan base. Yet artists often rely on these stans because they act as distribution and generate cultural conversations about why their favorite artist is the best.

These stans both hurt and benefit creators. Artists who do not fit this model are often ridiculed for being irrelevant or lacking a narrative. For many stans and even some music labels, talent alone is no longer enough. They want a larger structure built around the artist to push them into the mainstream. But as mentioned, this is not a healthy system to sustain.

Call me a hater, but I personally don’t like the Kendall Jenner Fanatics Super Bowl commercial. It promotes something harmful under the premise of sports banter, using the familiar strategy of irony and sarcasm to sell an ad that most people likely will not buy into but will share as a form of entertainment.

The same strategy was used by gambling brands in the UK. They wrapped their ads in sports banter and irony to deflect criticism. Fast forward to 2026, and many of the people who once defended those ads are now complaining about becoming walking advertisements for gambling, as nearly every jersey promotes a betting brand.

Even beyond gambling, brands relying on sports banter and celebrity culture feels lazy because that is not how you build a lasting brand. You cannot build a house on sand, and banter and celebrities are sand. We may be living in a post irony cultural moment, especially in meme culture, yet ad campaigns still rely too heavily on celebrities and on brands being ironic about themselves or something loosely relevant to them.

It is partly what contributed to the decline of Nike. Their ads remain entertaining, people enjoy the sports celebrity features, and the campaigns still evoke emotion. However, many cultural commentators, including voices like Joe Budden, argue that they no longer see what Nike is building beyond celebrity partnerships and advertising.

Good marketing does not automatically build a billion dollar brand.

Returning to gambling ads, in some ways they are worse than cigarette ads because they are less regulated and nearly everywhere. Every other reel I see on Instagram carries a gambling watermark. Polymarket reaches non-gamblers through breaking news and media gossip. Streamers switch platforms to promote gambling, and the ecosystem continues to expand.

It is not just Kendall. I see everyone promoting it, from LeBron to Gronk. Gambling and advertising can act like parasites. One is already consuming young men at an alarming rate, and the other threatens to erode sports culture.

It goes like this: IP → Nostalgia → Irony → Sarcasm. These are the safest bets brands make in their advertising. Irony may appear more creative than nostalgia, but it is not far removed from it. The greatest strength of irony in advertising is that it functions as a defense mechanism against criticism. It allows brands to say, take a breath, it is just a joke.

P.S. Gambling ads also benefit from stan culture, as the only fans defending their favorite athlete for appearing in a gambling ad are often those who are deeply invested in that athlete’s brand and legacy.

Most brands either overthink their communication strategy, or they confuse it with brand-product positioning. Overthinking looks like a brand trying to figure out its message before anything has been done in terms of a campaign or brand purpose.

Strategy comes before execution, but something else comes before strategy, ideation, research, and the annoying discussions that feel like we’re running in circles.

In my view, comms strategy is the preparation you do to simplify and identify the key objectives for the creative idea. Everything you do is for them to have a better understanding of the brand message.

Now, very often new brands and startups confuse communications with positioning. This problem comes up all the time with Silicon Valley startups, their comms plan is just copy-pasting the Hero section from their landing page. And sometimes that works because they had the product positioning sorted out. But that’s it. They can’t run the same ad copy all the time.

Comms strategy is more than brand positioning and messaging, it’s about how you communicate your brand in different formats, at different locations, and to different demographics. And you are supposed to ask more questions about your problems rather than wanting to have all the answers.

Ask yourself: do we have the resources to communicate our brand through XY channel? Do we have the talent to redesign our message for XY demographics? You only communicate what you can deliver.

It used to be that once you established all of that, you would ask the consumer, do, and show the research. But the story is much different now. On the performance side, almost everything is automated, and most brands don’t even waste time putting in first-party data unless they have something unique.

So on that side, whatever you want to communicate has to be part of the ad creative, showing your research through copywriting. On the social side, you have to be nonchalant, ironic, and target the social media content version of your audience to stay in the know.

The simplest answer to the question I posed is that brands gain access to consumers through online and offline spaces.

The biggest brands in the world, like Unilever, P&G, Estée Lauder, and Nike, don’t just win buyers because of marketing, they spend millions on shelf space at supermarkets, collaborations with online retailers, and global shipping to create a frictionless experience for the ideal buyer.

As much as you need a comms strategy, you need a distribution strategy to make sure your product is where your marketing reaches. Either start local or global, the choice is yours, but don’t rely too much on the will of the consumer, you tend to create their will.

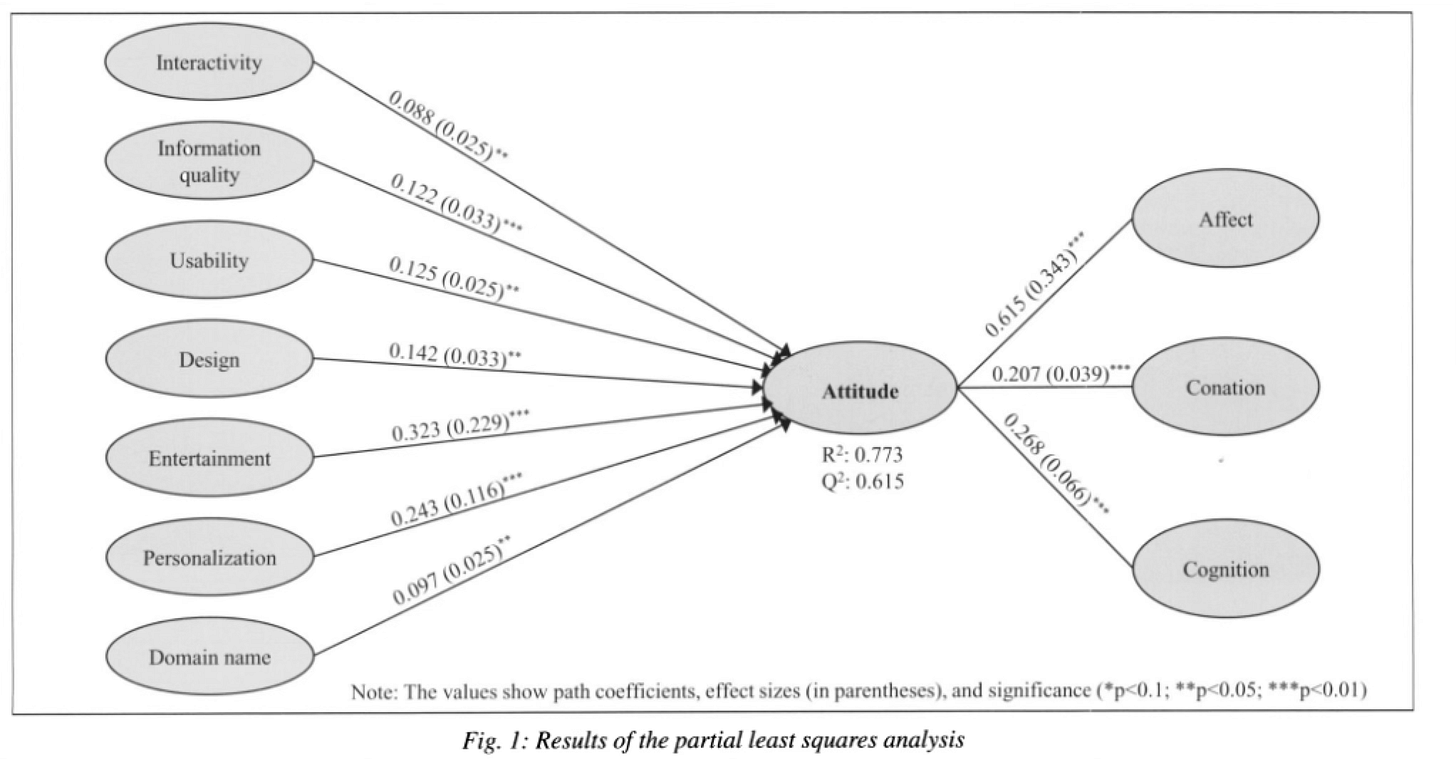

Online: While today it feels like content is all that matters to influence buyers, we have known for years that website UI/UX and bad personalisation in email marketing remain two of the biggest influences on why people abandon their carts and change their attitude.

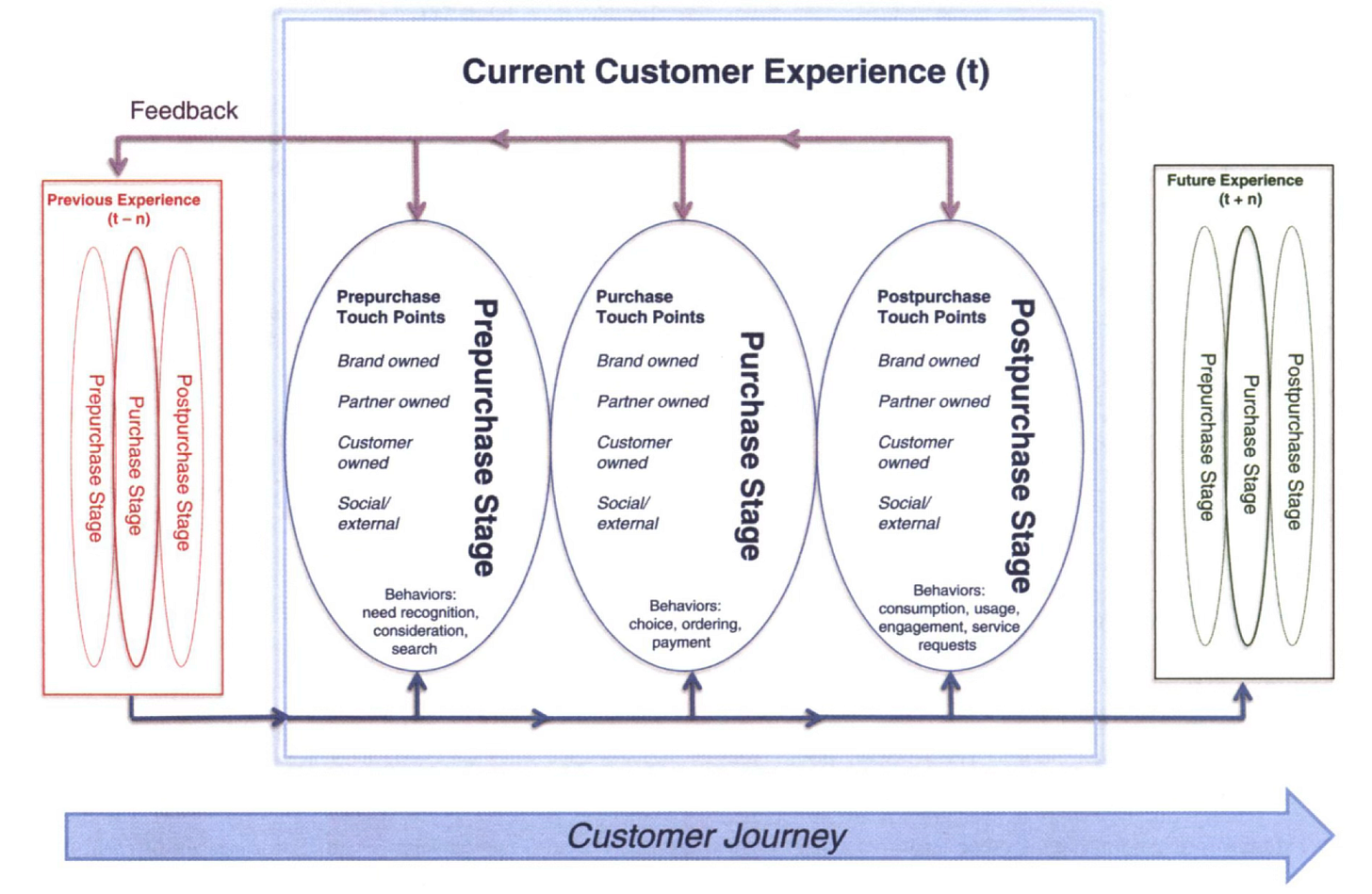

In the offline world, brands need to have a count of experiences that rely on customers’ actions, partners’ or retailers’ actions, and their own actions. A company should set up incentives for partners to provide a better experience and encourage customers to participate more in the journey.

The Loop: It starts with understanding what you are trying to communicate, and it ends with understanding how you are trying to communicate your brand. Everything else is checks and balances. More is never better. Communicate what is required, not all of what you have.

Don’t shout, because when you can’t reach consumers where they are, you only end up burning yourself out and wasting money. Communication without distribution is nothing. Show up before you tell.

-

People trying to create viral jingle for brands

-

People trying to create AI brand collabs

-

People trying products on live streams

-

People doing grocery hauls w/ brand tags

-

People judging new ads like paid critics

-

People doing nostalgia baiting with products

-

People who got laid off doing marketing tips

-

People begging brands to comment

-

People asking for PR gifts during a flight

-

People rocking t-shirts with multiple logos

-

People doing family challenges with intentional product placements

-

People reacting to comments from brands

-

People doing whatever for exposure

The story is simple. Consumerism is ingrained so deeply into how people live that they have taken on the role of being the product, the marketer, and the consumer.

You may say agencies can cater to these different scenarios and win new business, but most clients/brands believe they can do 50% of this by themselves. And the only need they see in ad agencies is management, which is why we are seeing so much consolidation and the rise of holding companies. The word is ‘people.’ They want their share of consumerism because they can’t escape it, but they can exploit it for their own benefit.

Back on Sunday. Until then…