Most people associate silver with money and wealth: jewelry, silverware, bullion and coins. No wonder, this precious metal is with us since the ancient times and has influenced our culture in many many ways. The recent rally (and crash) of the price of silver thus raised many eyebrows, calling the stability of the global economy, and the status of the dollar in it, into question. As usual, though, there is much more to the matter than what meets the investor’s eyes. The story of silver tells us as much about our “renewable” future, as about what comes next in the economy and in politics.

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription, or perhaps buying a virtual coffee. At the same time allow me to express my eternal gratitude to those who already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

The very first coin in the world—the Lydian lion, minted around 600 BCE—was made from silver. It has instantly revolutionized trade and enabled the standardization, storage, and exchange of value. Today, however, silver is first and foremost an industrial metal, with less than 39% of its supply finding its way to jewelers, vaults and safes. The rest, almost two thirds of all mined and recycled silver, ends up in electronics, solar panels, electric vehicles, missiles, and yes, AI data centers. The reason, as always, lies in the chemical and physical properties of this precious metal: silver exhibits the highest reflectivity, electrical and thermal conductivity of any metal—and thus has no one-to-one substitute.

While manufacturers are reducing silver content per each PV panel or electric car made through efficiency gains, the sheer scale of growth in these sectors is still driving a massive increase in silver demand. Problem is, the world simply cannot “produce” enough of this metal, hence the exponential rise in its price. In 2025 alone, demand outpaced supply by a whopping 118 million ounces—marking the fifth consecutive year when the market was in a physical deficit—resulting in a cumulative shortfall of 820 million ounces. That deficiency equals almost 1 year’s worth of mine output, accumulated in a mere 5 years. Think about that for a minute.

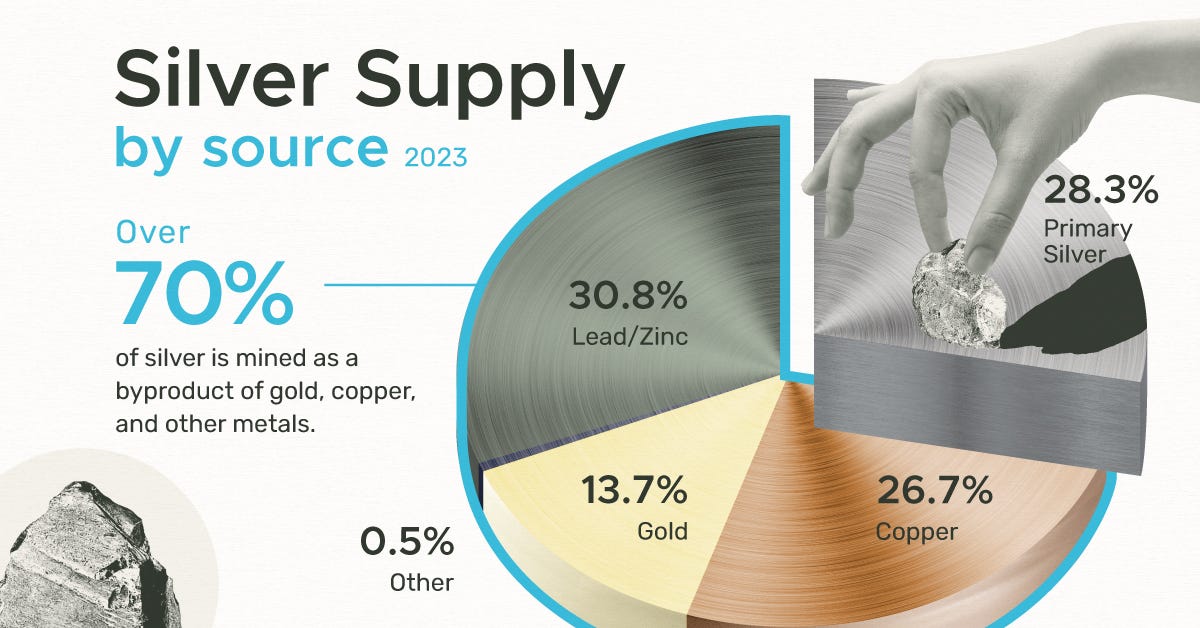

As to why is that so, one has to look no further than this chart, explaining the sources of silver supply. You see, only a little more than a quarter of all silver produced in the world comes from actual silver mines. The rest, over 70%, is actually a byproduct of zinc, lead, gold and copper production. And when those sources themselves struggle to meet demand, a shortage of silver arises as a result. As for a hint what might come next take a look at copper production, the third largest source of silver in the world. Global copper supply is expected to peak later this decade (at around 24 million tons) before falling noticeably to less than 19 million tons by 2035, as ore grades decline, reserves become depleted and mines are retired.

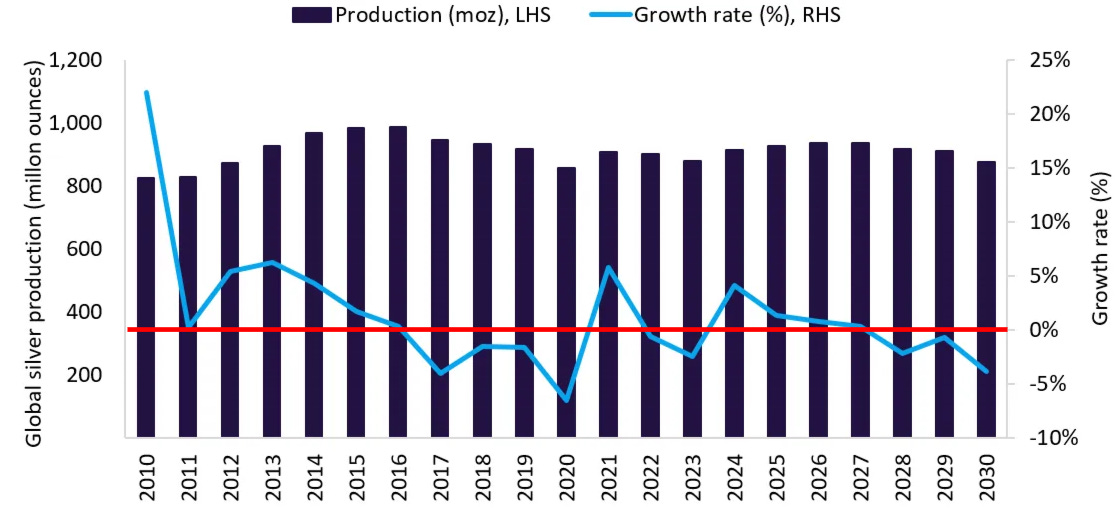

With that in mind, it’s really no wonder why the shape of silver supply forecasts look like a humpback whale: a gentle bulge followed by a long, dipping tail. With the growth rate turning negative from 2027 on, and accelerating towards a -5% decline, the next decade will most likely see an even sharper dip in silver supply than this one.

Looking at mine production alone—stripped of the effects of recycling—an absolute peak visibly emerges in 2016, combined with an uneven decline in the years to follow. Thanks to the same factors affecting copper production—declining ore grades, reserves becoming depleted and mines being retired—global silver production is projected to decline at an average rate of -0.9% year after year. One of the biggest contributors to this ongoing fall is Mexico, the world’s largest silver producer by far. The Latin American country was responsible for 25% of global output in 2024 at 6.3 thousand metric tons, but with reserves estimated at 37 thousand tons—equaling less than six years of production at the current rate—silver production there can only go one way: down. Considering that, and the long list of mines to be closed a -2.9% decline in Mexican silver output year after year seems to be all but guaranteed at this point.

While recycling did help to offset the imbalance somewhat so far, it’s mathematically impossible to feed a growing demand for any mineral with a persistent decline in mine output. As the authors of a fairly recent peer reviewed study (published in January, 2026) on the subject found:

“The results indicate that by 2030, supply may meet only 62–70 % of demand, which is projected at 48,000–54,000 t/y. The solar industry is expected to be the fastest-growing source of silver demand, reaching 10,000–14,000 t/y (29–41 % of supply). Despite slower growth, demand from competing sectors may rise to 38,000–40,000 t/y. As 72 % of primary silver is produced as co-product, significant expansion of primary output by 2030 is unlikely.”

So far we were able to plug holes in supply by using up previously accumulated stocks of silver and by increasing the rate of recycling. Since we are talking about rising demand, however, such stopgap measures won’t be enough. You see, first we would have to build those solar panels and electric cars which we could then recycle later. And since we are talking about an exponentially growing demand for products with lifetimes reaching twenty+ years, the unfolding silver supply crisis simply cannot hoped to be eased by recycling. Finally, consider the fact that a large number of people and banks view silver as a “store of value” or as part of their family heirloom—making them cling onto their bars and coins, jewelry and silverware as long as they can.

From an investment perspective the greater and more persistent the scarcity becomes, and the higher the price of silver climbs, the better. Unfortunately the same cannot be told about solar panel manufacturers, who are already under heavy pressure from intense competition. Rising input costs are already pushing them into an increasingly untenable position, as silver represented 14 percent of the total cost of production even at mid-2025 prices already… Since then the price of the shiny metal has doubled, then tripled for a brief period of time. And while PV makers can reduce the silver content of their products by switching to copper based technologies, that a) comes with a lower panel performance, and b) takes time and money—further investment into an already over-invested industry grappling with excess capacity. On top of all that, such measures would put further demand on the red metal—the production of which is also about to peak and decline before 2030. (And the price of which has already doubled since 2020 as a result.) Given these circumstances, the question of how do we continue—let alone accelerate—the “transition” towards ever more sophisticated “renewables” and electric vehicles worldwide is slowly becoming moot.

We live in a finite world, with only so much easy and profitable to extract metal ores. The rest, no matter how much more of these elements Earth’s crust may contain, will remain increasingly out of reach, as most newly discovered deposits are either too small to worth going after, lie to deep, or both. And if you consider that diesel fuel, the lifeblood of the machines mining and shipping these ores, is increasingly in short supply, too, you begin to grasp the fact that we are facing a converging supply crisis here. Something, which is not only threatening the “production” of silver and copper, but that of many other commodities as well.

This is how hitting limits to growth looks like in real life: not a sudden fall off the cliff but a long, slow whimper.

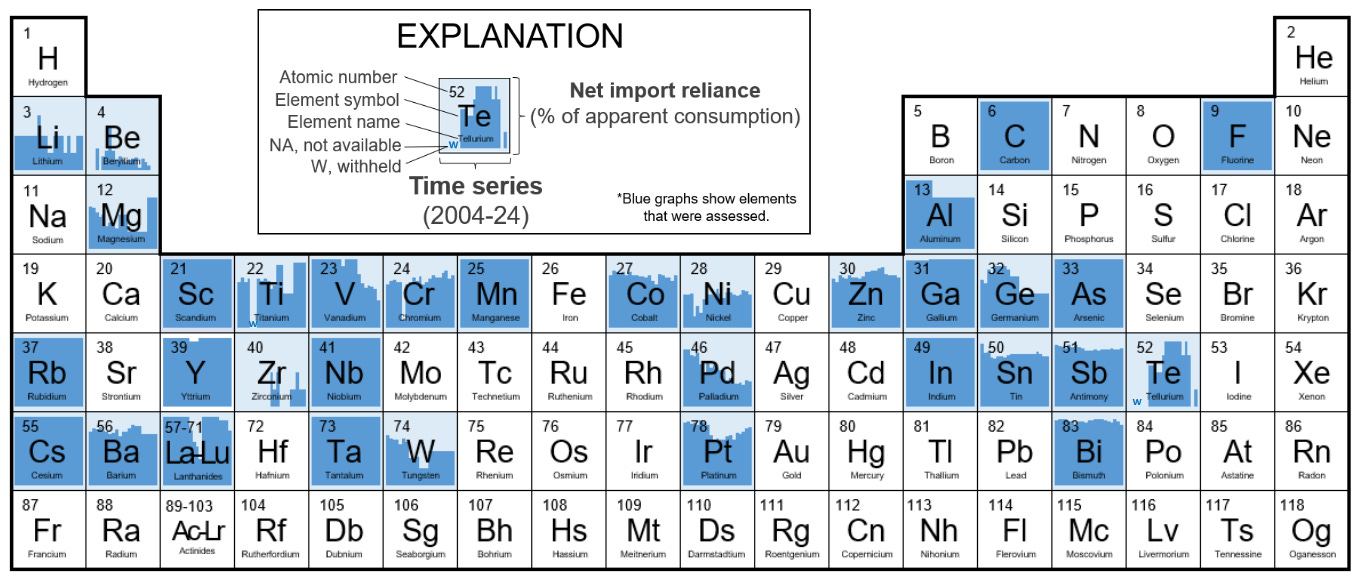

Given these circumstances, indicating the imminent end of material growth, is it any surprise that the U.S. Department of the Interior, through the U.S. Geological Survey, has put literally half of the entire periodic table on its 2025 List of Critical Materials? According to the survey, there are now 60 minerals vital to the U.S. economy and national security which “face potential risks from disrupted supply chains.” Whether that disruption comes from political decisions or, as we have seen above, is more and more due to resource depletion, does not seem to matter. The final list adds 10 new minerals—boron, copper, lead, metallurgical coal, phosphate, potash, rhenium, silicon, silver, and uranium. Take note, how previously abundant metallurgical coal (used primarily in making virgin steel) or phosphate and potash (essential to make fertilizer) found their way to the list—indicating that the world is entering an era of strategic competition for even the most basic pillars of modern civilization.

Barring a handful of exceptions, reliance on imports of critical minerals did not decrease over the past two decade. Put more bluntly, not much has happened. In fact, with the addition of silver and copper (among eight other elements) to the list, the overall dependence on imports seems to be just growing and growing—together with the realization that we are living in a material world, where stuff does seem to be built from real materials… Without which there is no stock market, healthcare, finance, and other services, making up the bulk of U.S. GDP. The recent rally in the price of silver is a case in point.

The scarcities we face today are mostly due to growing demand for stuff outstripping stagnating minerals supply. If mine output forecasts are anything to go by, however, this stagnation can be expected to turn into a decline for many critical elements: not only for silver, but also for copper, and most importantly: oil. Competition for, and control of, these dwindling resources will thus shape not only politics and international relationships, but will decide which economy can grow, and which must endure a decline in living standards as the price of everyday items and consumer goods continue to rise, often beyond the point of affordability.

Until next time,

B

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription, or perhaps buying a virtual coffee. At the same time allow me to express my eternal gratitude to those who already support my work — without you this site could not exist.