The Telecommunications Act of 1996 became law thirty years ago today, on February 8, 1996. Buried in a corner of that sprawling law was Section 230, a law that says websites aren’t liable for third-party content.

Section 230 didn’t receive much attention when it was passed, but it has since emerged as one of Congress’ most important media laws ever. Section 230 helped trigger the Web 2.0 era–where people principally talk with each other online, rather than just having content broadcast at them one-way. By enabling that discourse and other new categories of human interaction, Section 230 has thus reshaped the Internet and, by extension, our economy, our government, and our society.

Section 230 didn’t receive much attention when it was passed, but it has since emerged as one of Congress’ most important media laws ever. Section 230 helped trigger the Web 2.0 era–where people principally talk with each other online, rather than just having content broadcast at them one-way. By enabling that discourse and other new categories of human interaction, Section 230 has thus reshaped the Internet and, by extension, our economy, our government, and our society.

To commemorate Section 230’s 30th anniversary, this post considers Section 230’s past, present, and future.

* * *

Section 230’s Past

“Big Tech” Didn’t Lobby for Section 230. Google and Facebook didn’t exist in 1996; they emerged in the wake of Section 230’s passage. In 1996, the Internet industry was small, especially as compared to other media industries like cable or telephony. However, AOL played a key role in Section 230’s passage, as evidenced by the fact Section 230 uses statutory terms like “interactive computer service” and “information content provider” (a really terrible phrase) that mirror AOL’s idiosyncratic jargon.

The Internet Industry Didn’t Initially Celebrate Section 230’s Passage. I’m not aware of any fetes in 1996 that celebrated Section 230’s passage. That’s because Section 230 was overshadowed by another part of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the Communications Decency Act (CDA). The CDA imposed an unmanageable risk of criminal liability on Internet companies for user-generated content, so Internet executives were panicked that they might go to jail for the ordinary operation of their services. There was no time to get excited about Section 230’s long-term implications in the face of the immediate threat of criminal prosecution.

A week after the act’s passage, a district court enjoined the CDA, and the industry panic slightly abated. The industry relaxed a little more when the Supreme Court struck down the CDA as unconstitutional in 1997 (the Reno v. ACLU decision). However, that relief was short-lived because Congress quickly passed another law to criminalize user-generated content (the Child Online Protection Act of 1998, ultimately declared unconstitutional). So for years after Section 230’s passage, the industry was preoccupied by Congress’ UGC criminalization efforts.

Section 230’s Impact Wasn’t Immediately Clear. Section 230 includes some unusual and non-intuitive statutory language. As a result, the Internet industry wasn’t initially sure exactly what it said. Section 230’s potential scope only started to emerge after the district court ruling in Zeran v. AOL in March 1997. Then, after the Zeran v. AOL Fourth Circuit opinion in November 1997, it became clearer that Section 230 had reshaped the law of user-generated content. For more on the Zeran case, see this ebook.

Section 230 Left Open a Problematic “Copyright Hole.” Section 230 expressly excludes intellectual property claims based on third-party content. As a result, even after Section 230 passed, Internet services still faced potential secondary copyright liability with no statutory protection from Congress.

In particular, vicarious copyright infringement turns on a service’s “right and ability to control” the content on its servers, and plaintiffs can cite a service’s content moderation efforts–including those otherwise immunized by Section 230–as inculpatory evidence. In other words, Section 230 didn’t immediately legalize content moderation, because default copyright law still made those practices legally risky.

Two-plus years later, Congress partially plugged Section 230’s copyright hole in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998. In contrast to Section 230’s unconditional immunity for UGC, the DMCA created a notice-and-takedown liability scheme for user-caused copyright infringement. However, it took years for court cases to confirm that standard content moderation efforts didn’t increase services’ copyright liability for user-generated content.

Due to its unusual drafting and the legal context surrounding it, Section 230 didn’t definitively resolve the legitimacy of user-generated content and content moderation efforts when it passed in 1996. That implication took several more years to emerge.

For more on Section 230’s past, see Prof. Jeff Kosseff’s book, The 26 Words That Created the Internet. See also the 15-year retrospective event we held at SCU in 2011.

* * *

Section 230’s Present

Section 230 Offers Critical Procedural Benefits. Critics, politicians, and the media often focus their fire on Section 230’s substantive scope, such as how it compares to the First Amendment and whether it strikes the right policy balances. However, much of Section 230’s “magic” is procedural, not substantive. Section 230 provides courts with a helpful way of quickly dismissing unmeritorious cases. This, in turn, reduces defendants’ costs and increases their confidence of winning in court; and this further emboldens services to optimize their editorial policies for their audiences, engage in content moderation to effectuate those policies, and legally defend individual items of user-generated content. Even if the First Amendment dictated all of the same substantive outcomes as Section 230 (it doesn’t), Section 230 provides greater procedural predictability to the parties and thus achieves superior outcomes.

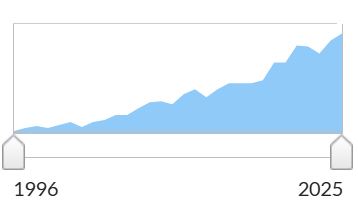

Section 230 Affects a Lot of Court Cases. According to the Shepard’s citation service, Section 230 has been cited in over 1,700 cases. As this figure indicates, citations keep going up:

Section 230 Discourages Many Lawsuits From Ever Being Filed. Section 230 has largely extinguished the genre of lawsuits against Internet services for their individual content moderation decisions. Without Section 230, every content moderation decision might prompt a lawsuit, manufacturing millions of potential lawsuits every day.

Section 230’s Drafters Future-Proofed the Law. Section 230 critics often highlight its adoption during the Internet’s infancy, as if that’s proof the law is not appropriate for the modern mid-2020s Internet. In 2020, Sen. Wyden and former Rep. Christopher Cox, the authors of Section 230, responded:

[Critics] assert that Section 230 was conceived as a way to protect an infant industry, and that it was written with the antiquated internet of the 1990s in mind – not the robust, ubiquitous internet we know today. As authors of the statute, we particularly wish to put this urban legend to rest…our legislative aim was to recognize the sheer implausibility of requiring each website to monitor all of the user-created content that crossed its portal each day…

The march of technology and the profusion of e-commerce business models over the last two decades represent precisely the kind of progress that Congress in 1996 hoped would follow from Section 230’s protections for speech on the internet and for the websites that host it. The increase in user-created content in the years since then is both a desired result of the certainty the law provides, and further reason that the law is needed more than ever in today’s environment.

* * *

Section 230’s Future

[TL;DR: 📉]

Congress Has Begun Chipping Away at Section 230. Congress has made two crucial reductions in Section 230’s scope in the past decade. In 2018, in FOSTA, Congress amended Section 230 to exclude immunity for commercial sex promotions. Then, last year, Congress passed the TAKE IT DOWN Act, which apparently overrides Section 230 to establish a notice-and-takedown scheme for intimate visual depictions.

Congress Could Repeal Section 230 at Any Moment. No politically powerful constituencies still publicly support Section 230. If a floor vote for a Section 230 repeal bill were scheduled in the House or Senate, I expect the repeal would pass by overwhelming margins.

Courts Are Repealing Section 230 Without Any Help From Congress. In 2024, in Anderson v. TikTok, the Third Circuit functionally repealed Section 230 in its circuit. The court said that any service that qualifies for First Amendment protections (which all online content publishers do) simultaneously cannot qualify for Section 230.

Separately, throughout the country, plaintiffs are pushing courts to hold websites liable for how they design their services because (they argue) such design choices are outside of Section 230’s scope. This argument is extremely problematic. A service’s “design choices” are synonymous with a publisher’s editorial decisions about how to gather, organize, and disseminate content. These are the kind of activities the First Amendment ought to protect. Further, for social media services that principally republish third-party content, “negligent design” claims could impose liability for that content–exactly what Section 230 should prevent. So long as courts are open to lawsuits over “design choices” and don’t apply Section 230 to those claims, plaintiffs will erode Section 230’s legal protections.

The Internet’s Future is Dire, Regardless of Section 230’s Fate. Fueled by the techlash, especially panics about children’s online usage, regulators are passing a tsunami of laws to regulate every aspect of how online publishers gather, organize, and disseminate content. Many of these laws are unconstitutional and violate Section 230, but legislators pay little heed to such concerns. Even if courts strike down most of these laws, the surviving laws will reshape how the Internet works.

In particular, legislatures are enacting laws that require online publishers to age-authenticate their users. These laws will have dramatic and universally negative consequences for the Internet, including raising publisher costs, shrinking publishers’ audiences, rewarding incumbents over startups, and creating massive privacy and security risks.

For these reasons, you should not assume that the Internet in 5 or 10 years will bear any resemblance to what we love most about the Internet today–no matter what Congress does to Section 230.

* * *

About the Author: Prof. Eric Goldman is Associate Dean for Research and Co-Director of the Datta Center for High Tech Law at Santa Clara University School of Law. He began practicing as an Internet lawyer, and teaching an Internet Law course, before Section 230 became law.

* * *

Want to read even more on Section 230? Check out some of my other articles on the topic:

* * *

Today is also the 30th anniversary of John Perry Barlow’s essay, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” his fever-dream response to the CDA’s passage. The opening paragraph is exquisite:

Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.

This essay is a culturally significant artifact because it had a tremendous impact on the mid-1990s discussions about Internet exceptionalism–even though the essay was always misguided and naive and has aged poorly.