In the late 2000s and early 2010s, as cloud computing emerged from nascency to enterprise adoption, awareness of each cloud provider’s strengths helped both individual practitioners and organizational decision-makers in selecting the correct cloud solution for specific scenarios, tasks, and organizational needs. Today, this same awareness is needed to prevent choosing the wrong AI for both individual tasks and organizational initiatives.

During the cloud wars, product managers and engineering leaders learned to distinguish:

-

AWS’s technical leadership and developer-first philosophy

-

Google Cloud’s startup-centric innovation and data analytics strengths

-

Microsoft Azure’s enterprise focus and bundling strategies through Enterprise Agreements

As such, technically proficient teams gravitated toward AWS’s depth, control, and operational excellence. Startups leveraged Google Cloud’s cutting-edge capabilities. Enterprises found comfort in Azure’s familiar licensing models and Microsoft ecosystem integration.

The understanding of each cloud provider’s DNA—their core philosophies, technical approaches, and go-to-market strategies—enabled leaders to select platforms matching their engineering culture, key strengths, and procurement processes. Understanding positioning wasn’t just helpful; it was essential for making technology choices that would compound advantages rather than create friction.

We stand at a similar inflection point in the AI landscape today. AI is moving beyond experimentation into production deployment. Long-running agentic capabilities—AI that can work autonomously for hours or days on complex tasks—become an expected reality rather than a research demo. As such, knowledge workers face a critical challenge: developing AI taste to know which AI to use when tackling a problem, no matter how small or big the problem is.

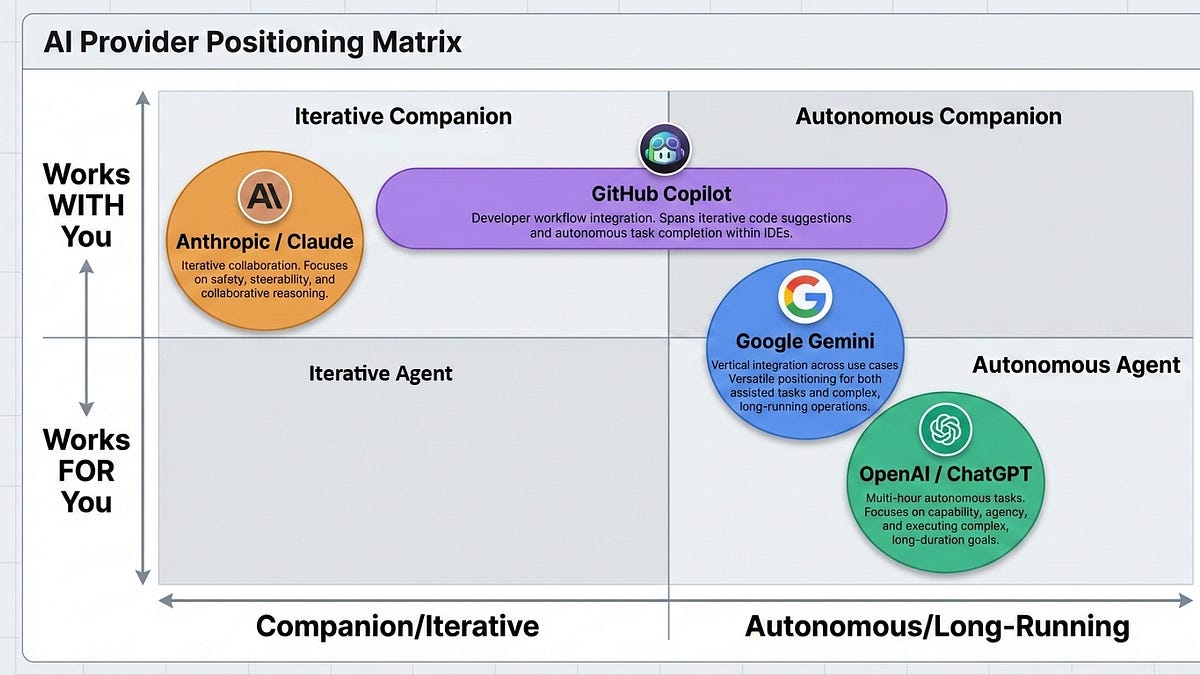

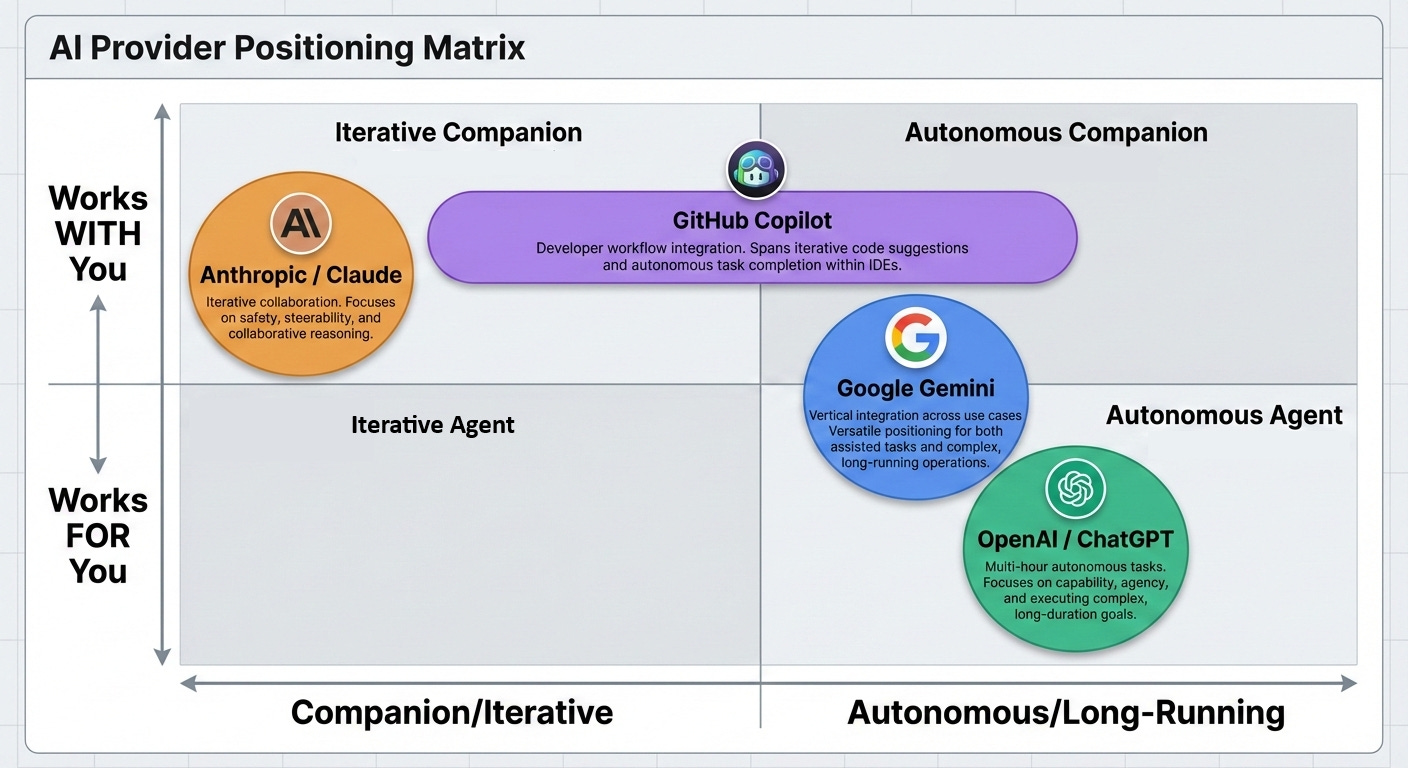

“AI taste” is a honed skill in matching AI providers to specific tasks based on each provider’s strategic positioning and strengths. It’s knowing when to use OpenAI versus Anthropic versus GitHub Copilot versus Google Gemini—not based on hype or brand recognition, but based on how each company’s technical implementation, training methodologies, and product philosophy align with the work you need done.

The stakes are high:

-

Individual knowledge workers (product managers, engineering leaders, content creators) waste time and produce inferior results when using the wrong AI for their tasks.

-

Engineering leaders building AI-powered products risk technical debt and poor user experiences when choosing misaligned foundations.

-

CTOs and budget holders make multi-year technology stack commitments without understanding which provider’s roadmap suits their organization’s DNA.

More critically, the executives who control technology budgets and set strategic direction need to understand how each provider’s roadmap, philosophy, and technical positioning align with their organization’s needs. Is your organization looking for AI that thinks with you or for you? Do you need AI that does things with you or does things for you? Do you need AI that aligns with your team’s top-down execution culture versus bottoms-up independent autonomy? These distinctions matter, and they map directly to the conscious positioning, technical implementation choices, and product philosophy that each AI provider has established.

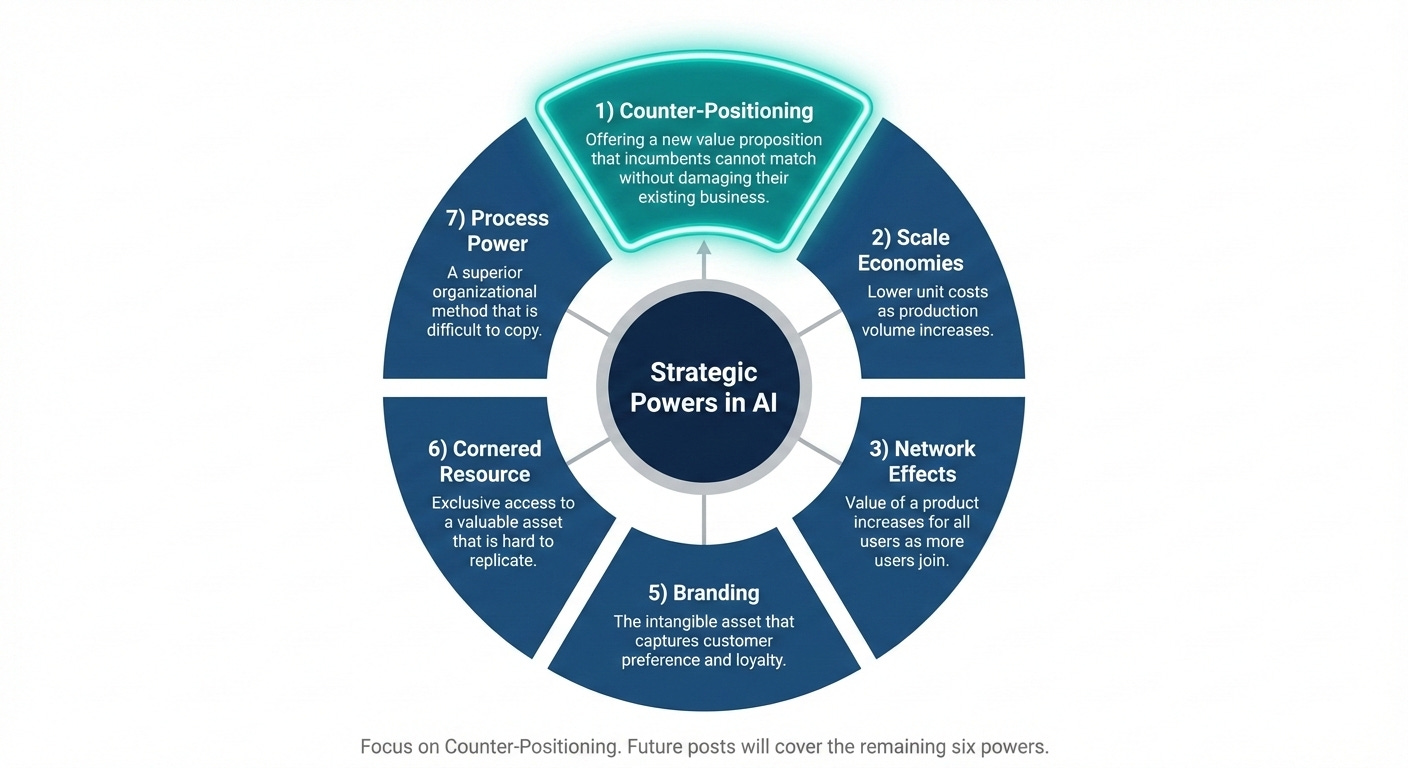

This series applies Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Framework—a rigorous strategic analysis tool—to systematically examine how OpenAI, Anthropic, GitHub Copilot, and Google Gemini have positioned themselves in the AI landscape. The seven powers are:

-

Counter-Positioning – Strategic choices, business models, or market positions that differentiate an AI provider from competitors in ways that are difficult or costly for competitors to replicate—whether due to cannibalization concerns (innovator’s dilemma), conflicting with their core identity, requiring abandonment of existing advantages, or simply being too narrow for a general-purpose strategy.

-

Scale Economies – Cost advantages that an AI provider accrues as usage increases

-

Network Effects – Whether value increases for all parties as more entrants adopt a provider

-

Switching Costs – Difficulty of changing providers

-

Branding – Premium pricing and lower customer acquisition costs from trusted recognition

-

Cornered Resource – Exclusive access to valuable assets enabling a provider to outdo competing providers on the other 7 powers.

-

Process Power – Embedded organizational excellence enabling a provider to out-execute competitors in a specific niche

This post focuses exclusively on counter-positioning—how each provider has carved out (or stumbled into) their strategic niche—sometimes positioning themselves in situations that run counter to popular narratives. Future posts will examine how each provider sustains and defends their position through the remaining six powers.

By analyzing how each company leverages these strategic powers through their product decisions, training methodologies, fine-tuning approaches, reinforcement learning techniques, and UI/UX patterns, we can develop practical guidance for task-appropriate AI selection.

Just as understanding cloud vendor positioning proved essential in the 2010s, developing AI taste through strategic analysis will prove essential for making informed decisions in the 2020s—whether you’re an individual choosing your daily AI tool, an engineering leader architecting your product’s AI capabilities, or a CTO setting your organization’s AI strategy.

Counter-positioning reveals the intentional niches that AI providers have carved out—or found themselves occupying—which form the foundation for their other strategic advantages. These niches emerge either from deliberate choices made in response to competitors capturing adjacent territory, or from circumstances where existing ownership of other parts of the wider tech ecosystem naturally positions a company for specific use cases. Understanding each provider’s counter-positioning clarifies why certain tasks align better with specific AI providers.

OpenAI occupies a unique position as the incumbent in mindshare despite not being the true incumbent in the development of LLMs, world models, or agentic AI. Google deserves credit for pioneering transformer-based language models, followed by Meta (then Facebook), but OpenAI was the first to achieve viral adoption. As Ben Thompson observed, ChatGPT was “an accidental consumer company”—OpenAI stumbled into becoming the default AI interface for the general public when they launched ChatGPT on X in November 2022. This allowed OpenAI to perfect the chatbot interface as the primary interaction paradigm, counter-positioning against the entire pre-ChatGPT era of knowledge lookup through search boxes.

-

Before ChatGPT (“BC”), users had to formulate Google search queries (initially keywords, evolving to phrases by the early 2020s). In BC, search boxes (not gimmicky chatbots) were the window to knowledge and information.

-

Alternatively during “BC”, users had to navigate directly to knowledge bases and articles (spanning GitHub docs, Amazon product pages, marketing blogs, news releases) when they knew exactly where to look.

-

Another common “BC” way of knowledge work (particularly in enterprises) was to rely on vertical solutions (domain-specific SaaS) or consultants to navigate knowledge work.

They made an accidental bet that successfully transformed the chatbox into the universal entry point for information retrieval and task completion, replacing the searchbox. It reduced the need for keyword search techniques, bookmark collections, knowing which specific pages to consult, or having the right vendor/consultant relationships.

OpenAI’s displacement of the searchbox with the chat interface seemed to place them in the Tech Hall of Fame… but the euphoria was short-lived. By late 2024, various frontier model providers devolved into a “benchmark game” where each model competed on how good its answers were in response to a set of prompts. Remember back in 2024 when your whole X feed was probably full of “some AI beats some other AI on some benchmark?” This state of affairs and intense benchmark focus led to controversial doubts on whether frontier AI companies (like OpenAI) even had a defensible moat at all. During those days, it seemed like frontier AI companies would devolve into low commodity-level margins, where the AI game was to be played based on raw power and money alone.

To break out of this “steady state of affairs” and “commoditization of AI” narrative, OpenAI did something in September 2024 that allowed them to break out of this depressing AI narrative. Instead of using its superior name recognition to secure even more funding to continue winning at the benchmark game at all costs, they counter-positioned against the AI industry by launching “multi-step reasoning capabilities” and “long-running autonomous agents.” OpenAI’s o-series models and deep-thinking systems represent a strategic bet on multi-hour and even multi-day task execution—a strategic bet that AI differentiation (opposite commoditization) will happen through increased AI autonomy.

Through force of will and consistent execution, OpenAI successfully thrust upon the world the notion that AI can be trusted to run longer without short feedback loops. In doing so, OpenAI (and the AI industry) prospered into 2025 as the sentiment shifted from “commodity models” to “value-accruing autonomous agents.”

The drive towards AI autonomy may seem common sense in hindsight, but looking back in 2024, practically no AI providers (aside from the ones named in this article) took such actions to differentiate themselves from what looked increasingly like a commodity race. For instance, Llama models (from Meta) and the Chinese models (back in 2024) were solely focused then on various benchmarks—without devoting much time and public strategies on differentiation! With OpenAI’s force of will to launching and evangelizing autonomous AI agents, your X feed now probably has more interesting AI use cases than mere benchmark results back then, right?

OpenAI’s focus on AI autonomy extends to their consistent messaging. Sam Altman and Greg Brockman have repeatedly publicly showcased this positioning on X (Twitter) throughout 2025, demoing 30-40 hour autonomous workflows (that sometimes stretches into days). OpenAI has unveiled specialized agents including security researchers that continuously analyze codebases (OpenAI Aardvark) and medical research agents that conduct extended literature reviews and new pharma discoveries. Altman’s X posts have emphasized that research capabilities and autonomous agents would become a core pillar of OpenAI’s positioning.

This counter-positioning toward extended reasoning and autonomous operation has created both opportunities and vulnerabilities. While OpenAI dominates scenarios requiring deep analytical work and long-running research, this focus has caused them to cede market share in other use cases—a dynamic that becomes evident when examining Anthropic’s positioning. As an anecdote, I’m frustrated at times by ChatGPT spending a few short extra seconds to “think” even for very simple questions, preferring instead to go with Anthropic’s more scoped companion approach which we cover later.

The most obvious play for the market leader (OpenAI) in a nascent field (AI) is to aggressively execute towards vertical integration to reap the potential rewards of scale economies. However, OpenAI has intentionally counter-positioned against this expected narrative by pursuing an ecosystem platform rather than pursuing vertical integration.

As Ben Thompson detailed in Stratechery, OpenAI has adopted a Wintel-like horizontal integration strategy, positioning itself as a platform where third-party services can plug in rather than building everything internally. ChatGPT’s product announcements over recent years have consistently emphasized partnerships with Expedia, Booking.com, Airbnb, Spotify, and Notion rather than competing with these services directly.

This ecosystem approach may not have been entirely intentional initially—OpenAI initially appeared committed to building proprietary SaaS platforms and to vertically integrate ChatGPT across the stack—but intensifying AI competition in 2024-2025 prompted them to lean more heavily into partnerships and platform economics as circumstances evolved.

Anthropic initially attempted to counter-position on safety concerns when the Amodei siblings and other OpenAI researchers departed just before ChatGPT’s explosive growth. However, Anthropic pivoted decisively over the past two to three years to position itself as the “AI companion” for knowledge work, recognizing an opening as ChatGPT became synonymous with autonomous task completion.

-

As mentioned, OpenAI optimized for scenarios where users paste long blocks of text and expect the AI to “figure it out.” OpenAI also optimized for scenarios that let agents “run continuously, or run for as long as needed, to autonomously accomplish and iterate on tasks.”

-

Anthropic identified that fully autonomous work represented a bridge too far for many use cases. The underlying infrastructure, LLM/world models, UI/UX patterns, and industry receptiveness to “unleashed AI” agents remained immature. Anthropic recognized that organizations needed something more iterative—an AI that embeds itself in knowledge work through iterative collaboration rather than automation.

This insight crystallized in Anthropic’s positioning statement, repeated across their marketing: “Claude is the AI that thinks with you and does things with you”—with explicit emphasis on “with you” rather than “for you.”

This positioning has proven remarkably effective for iterative work. When drafting PRDs, documents, blog posts, or conducting financial analysis on existing datasets, Claude has become the preferred choice among practitioners (including myself). The evidence appears consistently across professional communities: users on X and in enterprise settings report that Claude excels at writing documentation, coding assistance, and financial analysis because it operates collaboratively rather than prescriptively. As my friend Akash Singhal perfectly encapsulates this, OpenAI models “do too much”—they proactively suggest additional work, expand scope beyond what was requested, or implement features that weren’t explicitly prompted. Claude’s models, by contrast, focus tightly on the specific task at hand, thinking through the problem with the user rather than attempting to anticipate unstated needs. Another one of my friends (Leo Wang) observed that Claude is “more deterministic.”

This positioning has proven so effective that it has cost OpenAI significant market share. OpenAI executives including Sam Altman and Greg Brockman have acknowledged that their extensive focus on long-running tasks, “thinking” and research capabilities, and autonomous agents caused them to cede ground in collaborative workflows. OpenAI’s models optimized so heavily for reasoning that they began to “think too long” for many use cases—users became frustrated waiting for extended reasoning cycles when they simply wanted quick, focused assistance. Anthropic’s counter-positioning exploited this gap, capturing users who valued rapid, iterative collaboration over autonomous deep thinking.

Anthropic also did something unusual in early 2025 to break out of the benchmark commodity rat race: betting on the terminal interface when they launched Claude Code. Claude Code and its success in the terminal seems to be a given in hindsight.

But this was not obvious and is not something that the typical engineering leader or product visionary would have done. Common sense dictates that more polished, higher-level user interfaces—like text editors/IDEs, chatbots (on webpages and iOS/Android apps), and the browser—present more lucrative opportunities for monetization. Higher-level UI interfaces are where most AI providers have been (and still are) competing on.

Well, not for Anthropic’s Claude Code team. Anthropic’s Boris Cherny, Cat Wu, and Sid Bidasaria accidentally found internal product-market fit for interacting with AI agents through the terminal. The rest of Anthropic’s engineers, PMs, and pretty soon non-tech roles like Finance/HR found the terminal’s scripting and piping abilities to be a natural fit for AI agents. Recognizing its strong PMF, Anthropic leaned hard into Claude Code and the terminal interface, counter-positioning against other AI providers that could not execute on lower-level interfaces due to earlier bets on higher-level interfaces. For instance, Perplexity missed the CLI coding agent boat because they earlier bet the farm and were tied to its Perplexity Comet browser efforts. Perplexity (and others) shifting resources to lower-level interfaces (despite stronger PMF) would have required sheer force of will that few leaders possess.

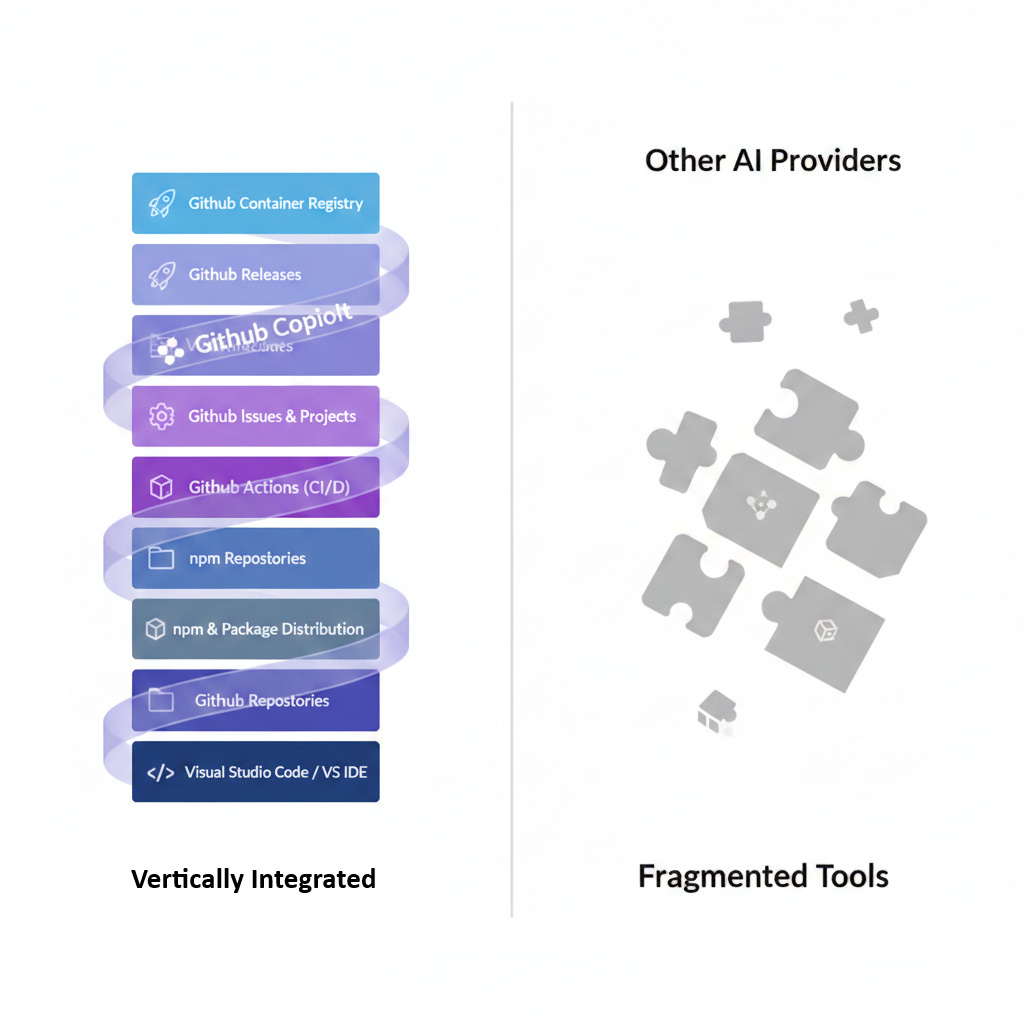

GitHub Copilot has maintained unwavering focus on coding and software project management as its exclusive domain since the pandemic-era launches of GPT-2 and GPT-3. While other AI providers pursued general-purpose positioning, GitHub Copilot has committed to software development and adjacent workflows as its focus, a strategic choice enabled by Microsoft and GitHub’s unmatched ecosystem assets. Intentionally focusing on a specific vertical (software development), where others are trying to win the general-purpose AI, is a pure form of counter-positioning. Only strong leaders like those at GitHub had the guts to draw the line, choose not to expand GitHub Copilot to other verticals and ignore the potential for flashy AI launches, and heads down focus only on coding.

Microsoft’s ownership and vertical integration of the following pieces create a complete environment for GitHub Copilot to capture a large share of AI-enabled software development:

-

GitHub Repositories host the world’s largest public code repositories, including complex, highly-active open source projects. These repositories also host some of the world’s largest public coding documentation (e.g., README files, AGENTS.md).

-

GitHub Actions operates as one of the largest public CI/CD platforms deployed across millions of diverse projects.

-

GitHub Releases serves as a major software distribution channel.

-

npm (Node.js package manager) and GitHub Container Registry extend this ecosystem into package distribution. Significantly, npm is emerging as a central distribution channel for local MCP servers and Agent Skills (SKILLS.md), positioning GitHub at the center of the agentic AI tooling ecosystem.

-

GitHub Issues and GitHub Projects provide coding-adjacent project management capabilities. While Atlassian Jira and Linear may dominate enterprise project management, and Azure DevOps serves Microsoft’s enterprise customers, GitHub’s project management offerings have achieved critical mass across open source and commercial development.

-

Visual Studio Code serves as the leading text editor and development environment. Its dominance is so complete that leading competing editors from other providers—Cursor, Google’s Antigravity—are all VS Code forks, forced to build on Microsoft’s foundation rather than competing from scratch. On the enterprise side, Visual Studio IDE maintains significant market share.

-

Programming language leadership: Microsoft’s stewardship of TypeScript enables GitHub Copilot to capture web development trends across frontend and backend frameworks, while its leadership in C# keeps Copilot aligned with enterprise software development paradigms.

GitHub can leverage its embedded position in every stage of the developer workflow to capture usage that might otherwise flow to general-purpose AI providers. The strategic positioning—strict software development focus and messaging—enables GitHub Copilot to compete effectively on two fronts simultaneously.

-

For companion-type coding tasks (the iterative, collaborative workflows that Anthropic has claimed as their territory), GitHub Copilot offers CLI and VS Code + VS IDE integration that allow developers to work iteratively on code with AI assistance embedded directly in their development environment.

-

For long-running autonomous tasks (the extended reasoning and research capabilities that OpenAI targets), GitHub Copilot can function autonomously to orchestrate complex workflows, automatically identify and remediate vulnerabilities through Dependabot’s security offerings and GitHub Advanced Security, and execute extended tasks through web-based orchestration by leveraging its GitHub Actions platform.

This dual capability represents GitHub Copilot’s special sauce: the potential to become the central platform for both software development and software project management across both companion-type tasks and autonomous operations.

The counter-positioning here relies on domain specificity—by focusing exclusively on software development rather than attempting to serve all knowledge work, GitHub Copilot can integrate more deeply and execute more effectively within the software development vertical, which is one of the largest verticals out there!

Google Gemini emerged as a late entrant to clear AI positioning due to regulatory constraints that prevented Google from executing an integrated strategy until late 2025. Prior to the favorable antitrust ruling, Google faced significant regulatory overhang from a pending case that threatened to break the company into two or more separate entities. This uncertainty prevented Google from freely integrating Gemini across its product ecosystem, as any aggressive integration moves could have been interpreted as anticompetitive behavior strengthening the case for breakup. In late 2025, the courts ruled that Google constituted a monopoly but declined to order dissolution, explicitly reasoning that maintaining Google as a unified entity would serve as a bulwark against other providers’ market power. This ruling freed Google to unleash Gemini integration (with surprising speed) across all its properties (evidenced by its rapid-fire launches in late 2025), fundamentally reshaping its competitive positioning.

In the months since the favorable ruling, Google has successfully positioned itself as the “vertically integrated Apple” of the current AI generation—a characterization articulated by Ben Thompson in Stratechery. Where OpenAI offers a Wintel-style horizontal platform approach (becoming the platform that other applications build upon), Google’s vertical integration strategy extends across email, calendar events, productivity suites, collaborative tools, hardware devices (Pixel + Google Home), and mobility (Waymo). This creates a seamless experience for general-purpose AI that no other providers can match without building parallel infrastructure.

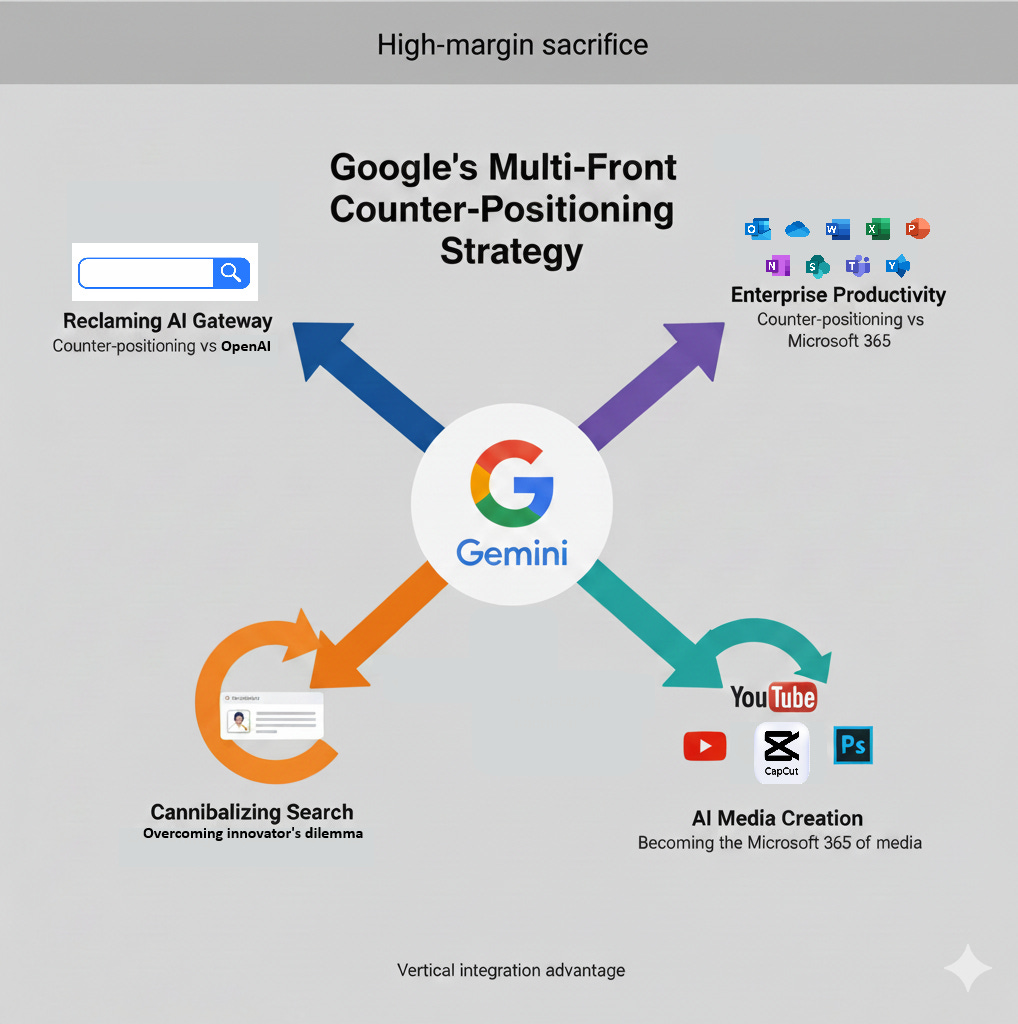

We will see how Google has counter-positioned (in multiple instances!) against competitors, and counter-positioned against itself, to overcome the several innovator’s dilemma that previously threatened Google.

For the past three years, since the launch of ChatGPT, a persistent question has dominated industry discourse. Would AI agents cannibalize Google Search’s lucrative margins and chip away at its market share? Would Google Search go the way of Internet Explorer, with ChatGPT becoming the new point of integration?

The fear had historical precedent. Google Search and Google’s bet on the open internet once made Google the point of integration during the rise of the internet, counter-positioning against Microsoft’s Windows and desktop-centric strategy. Now there was a persistent fear that OpenAI and ChatGPT represented a similar counterposition against Google. This new paradigm threatened to disintermediate search entirely, as we’ve discussed earlier.

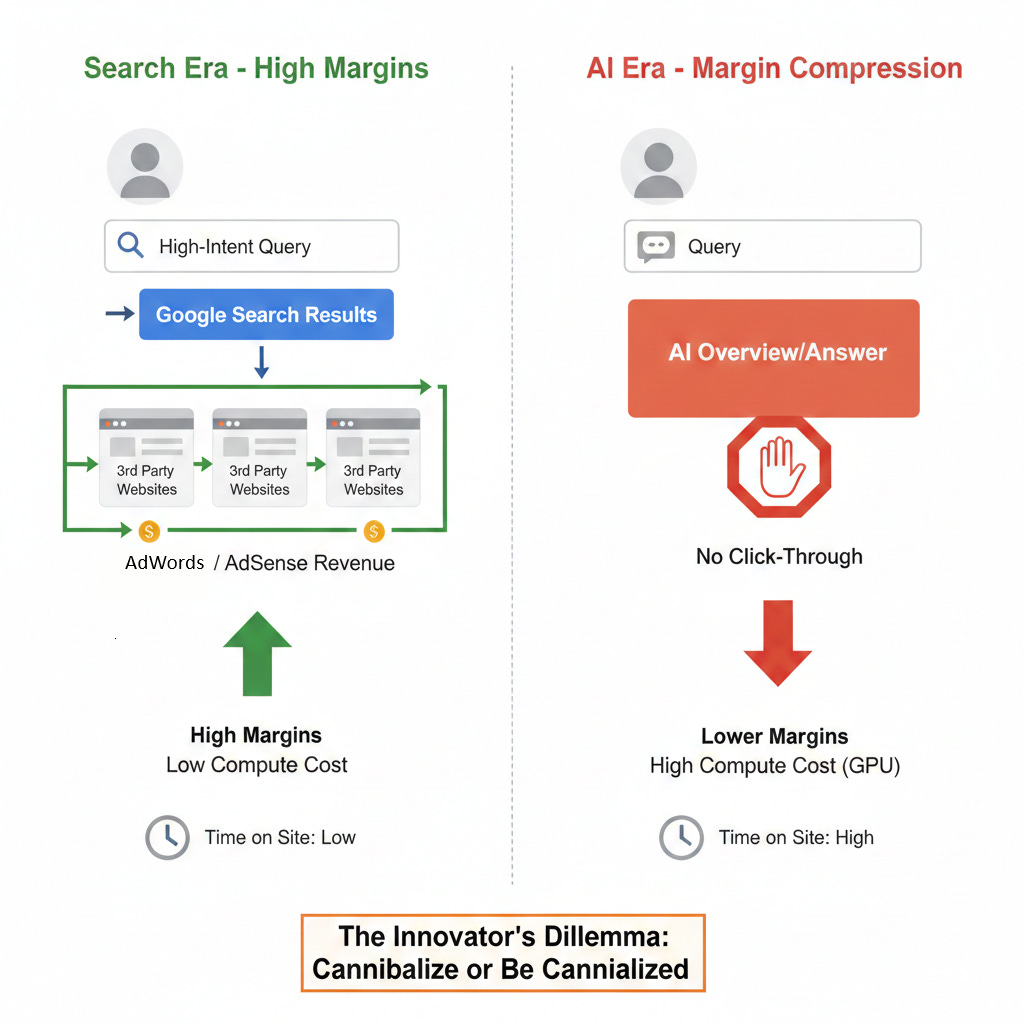

The Search Era Economics: High Intent, Low Time-on-Site

Google’s dominance in the search era rested on a deceptively simple model: capitalize on high-intent user behavior while keeping time-on-site minimal. Search represented high-intent activity—users arrived to Google.com knowing what they wanted to find. Google monetized this intent brilliantly through AdWords (search keyword bidding) and AdSense (banner ad network), placing ads precisely where intent peaked. Success meant getting users OFF google.com as quickly as possible to partner sites, whether through paid ads or organic results.

This model generated extraordinary margins. Keyword search and ad serving required minimal compute resources (relative to AI)—no expensive inference, no continuous model training. The infrastructure costs were modest relative to the advertising revenue generated. Google had built what every business dreams of: a high-margin cash machine that scaled effortlessly. As Ben Gilbert and David Rosenthal from the Acquired Podcast put it, Google created possibly the best business model of all time with search and ad monetization.

The AI Threat: When Answers Replace Destinations

AI overviews fundamentally shatter this economic model. When users receive comprehensive AI-generated answers directly in search results, they stay ON Google rather than clicking through to partner sites. A search for health information that once drove traffic to Healthline, Mayo Clinic, or WebMD—generating AdWords revenue from keyword bids and AdSense revenue from banner ads on those sites—now terminates in an AI overview. The user gets their answer, Google loses the click-through, and the entire advertising ecosystem suffers.

This represents a classic innovator’s dilemma, made more painful by the margin compression. AI inference is computationally expensive—requiring substantial GPU resources for every query. Google faces the prospect of replacing a high-margin, low-compute business (search) with a lower-margin, high-compute alternative (AI Overviews and AI chats). The addiction to high-margin revenue is powerful—like refusing to quit despite knowing the long-term consequences.

Overcoming the Innovator’s Dilemma: Deliberate Self-Cannibalization

Google, after the regulatory overhang lifted in 2025, made the courageous choice to counter-position against itself in search. Under renewed leadership focus from Sundar Pichai, Sergey Brin, Jeff Dean, Demis Hassabis, Noam Shazeer, and others, Google aggressively launched AI overviews in search results. They recognized the brutal truth: if they didn’t cannibalize their own search business, someone else would. Whether OpenAI’s ChatGPT interface, Perplexity, or another competitor, the threat of disintermediation was real and imminent.

This counter-positioning strategy operates on multiple fronts. Google embedded Gemini prominently in Chrome—the default gateway through which most users access the internet. The irony is elegant: users access ChatGPT through Chrome, yet Google leverages this superior positioning to place Gemini front-and-center, potentially recapturing the mental association of “AI chatbox” from ChatGPT back to Google’s own AI.

Beyond Chrome integration, Google leaned heavily into AI overviews and AI chat interfaces as the replacement for search-centric experiences. This required embracing a fundamental uncertainty: the monetization paradigms and high-margin potential for ads within chat interfaces have not yet become apparent. Google is deliberately moving from a proven, lucrative advertising model to an unproven one, accepting lower margins and unclear monetization in exchange for maintaining relevance in the AI era.

This is counter-positioning in its purest form—sacrificing today’s profits to secure tomorrow’s position. Google chose to disrupt itself rather than be disrupted, successfully navigating one of the most difficult challenges any incumbent faces.

Let’s move onto office productivity software where Microsoft dominates with Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. Google’s counter-positioning against Microsoft in enterprise productivity AI represents a classic innovator’s dilemma scenario for Microsoft.

-

Microsoft has spent years emphasizing that Microsoft 365 is strictly enterprise-focused and does not train on customer data—a privacy commitment that served as a competitive advantage in the pre-AI era. However, this commitment now constrains Microsoft 365 Copilot’s ability to improve. Microsoft faces an impossible choice: if they don’t train on enterprise customer data, their productivity AI cannot learn from actual business workflows; if they request permission to train, enterprises will refuse due to proprietary data concerns.

-

Google, by contrast, can approach enterprises with a compelling value proposition: “Our Google Workspace AI (Docs, Sheets, Slides) will be superior to Microsoft 365 Copilot precisely because we train on the massive corpus of free Google accounts and YouTube content. As a paying enterprise customer, you receive peace of mind that we will never train on your proprietary data, yet you still benefit from AI trained on billions of documents, presentations, and videos from our free tier.”

Google’s historical weakness—privacy concerns about free product data usage—transforms into a strategic strength in the AI era. The free tier that critics once questioned now enables Google to deliver superior enterprise productivity AI without requiring enterprises to sacrifice their data privacy, while Microsoft’s enterprise-only positioning leaves them unable to train effectively on productivity workflows.

Google’s strength in AI productivity suites is already apparent with NotebookLM’s impressive capabilities across docs, slides, sheets, and presentations. As AI advances, I expect Google and NotebookLM’s lead in productivity capabilities to expand, which could lead it to finally landing enterprise agreements to chip away at Microsoft 365.

Google already hosts one of the largest repositories of content across multiple media types. To understand how Gemini positions as the comprehensive AI media platform, we need to examine both text-based and media content separately.

Text-Based Content: From SEO Partner Ecosystem to In-House AI Optimization

For over two decades, Google cultivated a thriving horizontal partner ecosystem around search engine optimization, where SEO experts and content marketers built businesses helping publishers optimize for Google search results. This horizontal approach was high-margin—Google maintained the platform while partners delivered the optimization services. The AI era threatens this equilibrium. When users receive answers from AI chatbots rather than clicking through to websites, traditional SEO becomes less valuable, and publishers need to optimize for appearing in AI-generated responses across ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and other platforms.

Given Google’s aggressive verticalization strategy across other domains—from Chrome integration to hardware consolidation to productivity suites—a similar move in content optimization seems possible, though no early indications exist yet. If Google follows this pattern, they could bring AI optimization tools in-house, offering publishers: “We’re the experts at getting your content discovered. Now we’ll provide tools to ensure your content appears effectively in AI-generated answers—not just in Gemini, but across all AI platforms.”

This would represent counter-positioning against their own successful partner ecosystem, sacrificing margins for lower-margin in-house tools. The strategic question remains: will Google verticalize here too to defend their position as the gateway between content creators and consumers in the AI era?

Video and Graphical Media: Becoming the Tooling Platform for AI-Generated Content

The current market structure for video and graphical media is clear: value sits with five major players—YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Netflix, and traditional legacy media. Everyone in the ecosystem recognizes where the distribution power and audience attention reside. Historically, Google and YouTube maintained this distribution dominance while ceding content creation tooling to specialized incumbents: Adobe for video editing, CapCut for short-form video production, and various other providers for audio and podcast creation.

Google’s vertical integration across content creation platforms—spanning video hosting, discovery, monetization, and now increasingly sophisticated AI capabilities—positions them similarly to how Microsoft sits across the entire software development workflow. This creates a counter-positioning opportunity: rather than continuing to rely on third-party creation tools, Google could become the “VS Code” or “Microsoft 365” of media creation. The scope is comprehensive—video editing, graphical content, audio production, podcast creation—essentially all the tooling needed to produce text-based, video, graphical, and audio media that ultimately gets distributed through these platforms.

Media has consistently proven to be high-margin across eras—from radio to television to internet distribution. By leaning into AI-powered media creation tooling, Google could differentiate from all other AI providers who focus primarily on text-based generation or general-purpose assistance. Early indications suggest this strategy is already unfolding: NotebookLM demonstrates sophisticated capabilities for generating various media formats, Veo + Nano Banana Pro is already used by brands for video ad campaigns, while Google Labs continues releasing AI media creation and AI marketing tools. These include Google Labs Pomelli which they positioned as the all-in-one branding/content kit generator, or Google Labs Doppl, a try-on generator that ecommerce brands will find useful, providing Google a beachhead in capturing media for agentic ecommerce (which is an area OpenAI/Stripe also want to get into!)

Google appears to be positioning its AI offerings as not just as a content consumer or distributor, but as the comprehensive platform that powers content creation itself—the Microsoft 365 of AI-generated media—spanning AI-generated media that is meant for consumer consumption (movies/short form Reels-like videos), marketing campaigns, or lucrative ecommerce media.

To sum it up, among all major AI providers, Google faces the most severe innovator’s dilemma—their high-margin search business and established product portfolio create powerful incentives to preserve the status quo.

Yet paradoxically as we’ve discussed, Google also possesses unique capability to escape this trap through aggressive vertical integration across three critical domains:

-

general-purpose AI (reclaiming the AI mental association from ChatGPT, reclaiming the portal to the internet through Chrome and AI overviews)

-

enterprise productivity (becoming the Microsoft 365 of the AI era)

-

AI content creation (becoming the Microsoft 365 for media production).

Where OpenAI offers a horizontal platform approach, Google’s vertical integration delivers seamless experiences across search, productivity, media, hardware, and mobility that no competitor can replicate without building parallel infrastructure.

The question is not whether Google faces the most daunting innovator’s dilemma—they clearly do. The question is whether they will continue executing on their multi-vertical counter-positioning strategy, accepting lower margins and uncertain monetization to maintain relevance in the AI era. Early evidence from late 2025 suggests they’ve made this choice.

Counter-positioning reveals where each AI provider has chosen to compete—the strategic niches that form the foundation for their competitive advantages:

-

OpenAI positioned as the autonomous agent platform, counter-positioning AI against the incumbent “search box” gate to the internet. They also positioned against the competition by optimizing for long-running research tasks and deep reasoning while adopting a horizontal ecosystem strategy reminiscent of Windows/Intel.

-

Anthropic counter-positioned as the collaborative companion, capturing users who need iterative “thinking with you” workflows rather than autonomous “doing for you” agents.

-

GitHub Copilot maintained laser focus on software development, leveraging Microsoft’s unmatched vertical integration across the entire developer workflow to fight effectively on two fronts simultaneously.

-

Google Gemini emerged from regulatory constraints to execute aggressive vertical integration across general-purpose AI, enterprise productivity, and AI content creation—counter-positioning against both competitors and its own high-margin legacy businesses (search, ads).

Understanding counter-positioning reveals where each AI provider competes. But positioning alone doesn’t guarantee success. In upcoming posts, we’ll examine how OpenAI, Anthropic, GitHub Copilot, and Google Gemini leverage the remaining six powers—Scale Economies, Network Effects, Switching Costs, Branding, Cornered Resources, and Process Power—to sustainably defend and execute their strategic positions.