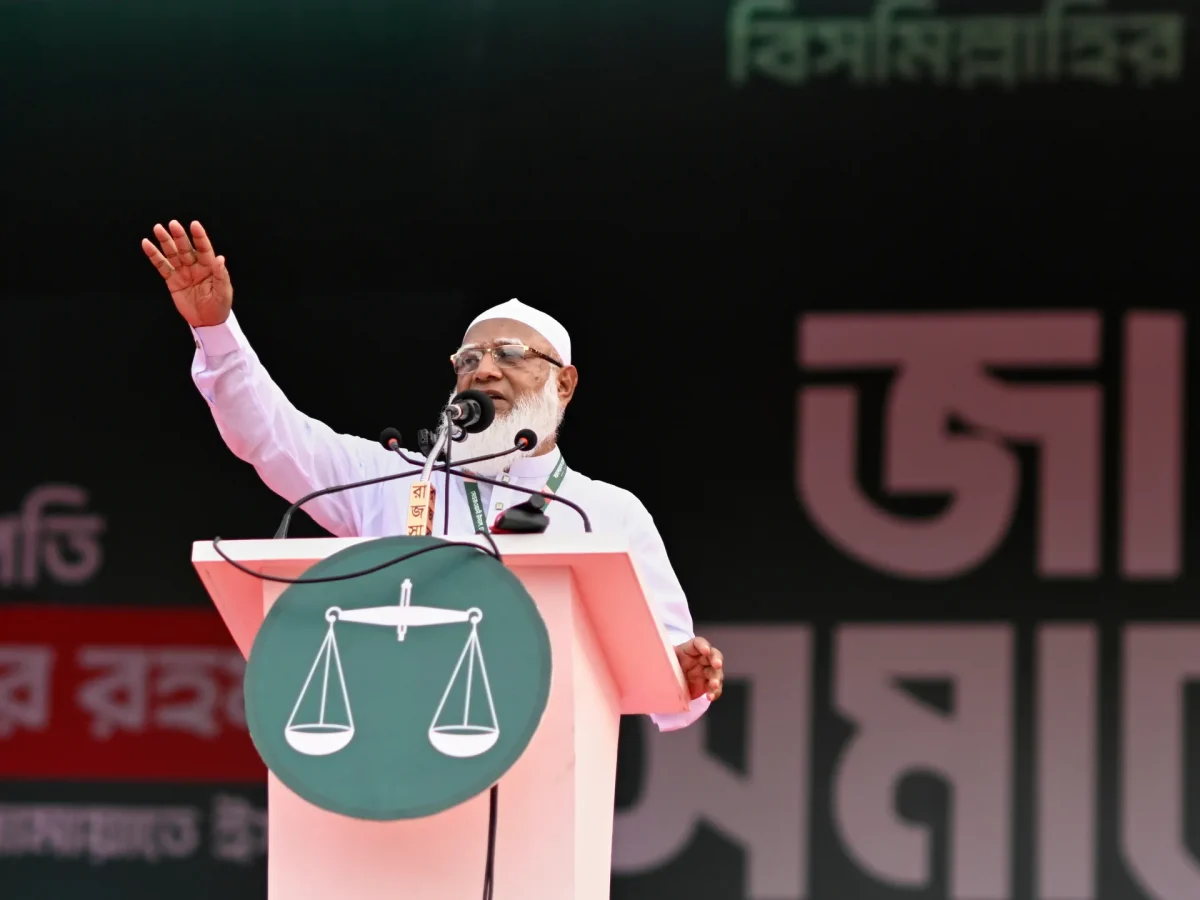

Dhaka, Bangladesh – On Wednesday evening in Dhaka, Shafiqur Rahman, the emir [chief] of the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, unveiled an ambitious election manifesto. A key promise: If his party wins the country’s February 12 election, it would lay the ground for Bangladesh to quadruple its gross domestic product (GDP) to $2 trillion by 2040.

Addressing politicians and diplomats, the 67-year-old Rahman pledged investment in technology-driven agriculture, manufacturing, information technology, education and healthcare, alongside higher foreign investment and increased public spending.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

Economists in Dhaka have cast doubt on whether sweeping promises can be financed, describing the manifesto as heavy on slogans but short on detail. But for Jamaat’s leadership, the manifesto is less about fiscal arithmetic than signalling intent, say analysts.

For years, critics have tried to portray Jamaat, Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party, as driven too much by religious doctrine to be able to govern a young, diverse, forward-looking population. The manifesto, by contrast, presents a party long excluded from power as a credible alternative – and as a force that sees no contradiction between its religious foundations and the modern future that Bangladeshis aspire to.

His audience was telling too.

Until recently, Bangladesh’s business elites and foreign diplomats either kept their distance from Jamaat or engaged with it discreetly. Now, they are doing so openly.

Over the past few months, European, Western and even Indian diplomats have sought meetings with Rahman, a figure who until not long ago was seen by many, internationally, as almost politically untouchable.

For a leader whose party has been banned twice, including by ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s administration, the coming election is raising a question few would have dared to ask even a year ago: Could Shafiqur Rahman become Bangladesh’s next prime minister?

‘I will fight for the people’

The shift in how Jamaat and its leader are being viewed is at least partly to do with a political vacuum that has opened up in Bangladesh.

The July 2024 uprising that ousted Sheikh Hasina did more than end her long rule. It upended the country’s political order, hollowing out the familiar duopoly that for decades defined Bangladeshi politics – the rivalry between Hasina’s Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).

With the Awami League effectively barred from the political field and BNP the only major party left standing, a vacuum emerged. Many initially assumed it would be filled by the student-led National Citizen Party (NCP). Instead, Jamaat – long pushed to the margins – moved to occupy the space.

As Bangladesh heads towards a high-stakes election in less than two weeks, Jamaat has now emerged as one of the country’s two most prominent political forces. Some pre-election polls now place it in direct competition with the BNP.

At the centre of that transformation is Rahman, according to Ahsanul Mahboob Zubair, Jamaat’s assistant secretary-general and a longtime associate of the party chief.

Zubair, who worked closely with Rahman when he led Jamaat in the country’s Sylhet region, said the resurgence is the result of years of grassroots social work and political survival under repression.

Rahman, a soft-spoken former government doctor, took over as Jamaat’s chief in 2019, at a time when the party was banned under Hasina. In December 2022, he was arrested in the middle of the night on charges of supporting militancy and was released only after 15 months when he secured bail.

In March 2025, months after the student-led protest had overthrown Hasina, and an interim government under Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus had taken office, Rahman’s name was dropped from the list of accused in the case.

Since then, his carefully calibrated, emotional public appearances have drawn wide attention.

At a massive rally in Dhaka last July, Rahman collapsed twice on stage due to heat-related illness but returned to finish his speech, defying doctors’ advice.

“As long as Allah grants me life, I will fight for the people,” he told the crowd, barely sitting on the stage, supported by the doctors. “If Jamaat is elected, we will be servants, not owners. No minister will take plots or tax-free cars. There will be no extortion, no corruption. I want to tell the youth clearly – we are with you.”

Reinventing Jamaat’s image

Supporters describe Shafiqur Rahman as approachable and morally grounded – a leader who prefers disaster zones to drawing rooms, and projects calm in a country exhausted by confrontation.

Now in his third term as chief, Rahman commands firm authority inside the party.

“He is a good and pious man. Everyone in the party trusts him,” said Lokman Hossain, a Jamaat supporter in Dhaka. He said that over the past year and a half, the party has reached far more people than before, with Rahman’s appeal beyond Jamaat’s traditional base playing a central role.

Rahman’s challenge, however, is no longer purely electoral – it is reputational.

As new supporters drift towards Jamaat, he is attempting to reframe how the party is seen: less as an Islamic force defined by doctrine and history, and more as a vehicle for clean governance, discipline and change.

Whether this reinvention is substantive or merely cosmetic will define both Rahman’s leadership and Jamaat’s future, say analysts.

Any attempt to recast Jamaat’s public image, however, runs up against the unresolved legacy of 1971. For decades, the party’s role during Bangladesh’s war of independence – when it sided with Pakistan – and the subsequent trials and executions of several senior leaders have shaped perceptions of Jamaat at home and abroad.

Rahman has approached that history with caution. He has avoided detailed admissions but has recently acknowledged what he calls Jamaat’s “past mistakes”, asking forgiveness if the party caused harm.

The language marks a subtle shift from outright denial, while stopping short of naming specific actions or responsibilities. Supporters say this reflects political realism rather than evasion – an attempt to move the party beyond its dark chapter. Critics, by contrast, see the ambiguity as deliberate, arguing it softens Jamaat’s image without confronting the substance of its past.

“He knows what those mistakes were,” said Saleh Uddin Ahmed, a United States-based Bangladeshi academic and political analyst. “But stating them explicitly would destabilise his leadership inside the party.”

Ahmed nonetheless considers Rahman more moderate than Jamaat’s previous leaders, noting his relative willingness to discuss unresolved historical questions and address issues such as women’s rights – topics the party long avoided. “This opening up is also happening because of increased public and media scrutiny,” Ahmed said. “People are asking questions now, and Jamaat has to respond.”

Jamaat’s effort to reach voters beyond its traditional base and reassure foreign audiences, while retaining the loyalty of its conservative supporters, has created a persistent tension – one that has often resulted in dual messaging.

That balancing act has been evident in public statements by senior leaders. Abdullah Md Taher, one of Rahman’s closest aides, in an interview with Al Jazeera, said Jamaat is a moderate party, adding that it would not impose or strictly adhere to Islamic law.

The party has also, for the first time in its history, nominated a Hindu candidate.

Yet when addressing conservative supporters, the party continues to emphasise its Islamic identity, with some backers encouraging votes for Jamaat as an act of religious merit – a practice the rival BNP has criticised as the misuse of religious sentiment.

The strategy appears to have helped Jamaat re-enter political conversations that were once closed to it. At the same time, it has sharpened doubts about how far Rahman is willing – or able – to go in reinterpreting the party’s past and ideology as he courts a broader electorate.

Those limits are most visible in the Jamaat’s stance on women and leadership. They came into sharp focus during his Al Jazeera interview in which Shafiqur Rahman said it was not possible for a woman to hold the party’s top position – a remark that reignited longstanding criticism of Jamaat’s gender politics, despite its attempts to project a more inclusive image.

“Allah has made everyone with a distinct nature. A man cannot bear a child or breastfeed,” Rahman said. “There are physical limitations that cannot be denied. When a mother gives birth, how will she carry out these responsibilities? It is not possible.”

Critics argue that the stance exposes the limits of Jamaat’s claims of moderation.

Mubashar Hasan, an adjunct researcher at the Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative at Western Sydney University in Australia and author of Narratives of Bangladesh, also questioned Jamaat’s internal culture, noting that even female leaders who publicly endorse such views operate within a male-dominated hierarchy. He was referring to the party’s large number of female supporters and members, including women within its Majlis-e-Shura, the highest decision-making body. “It reflects a structure where women follow what men says in that party,” he said.

The criticism carries particular weight given the movement that helped reopen political space for Jamaat itself. The July 2024 uprising against Hasina, analysts note, saw extensive participation by women, often at the front lines of protest. “Women were part of that movement as much as men, if not more,” Hasan said. “Undermining them now gives Jamaat a deeply problematic outlook.”

Political historians argue this is not a new contradiction but a longstanding one. Since contesting elections under its own symbol in 1986, Jamaat has never fielded a woman candidate for a general parliamentary seat, relying instead on reserved quotas.

“This isn’t a temporary position or a tactical lapse,” said political historian and author Mohiuddin Ahmad.“It reflects the party’s ideological structure, and that structure has not fundamentally changed.”

The ‘grandfather’ expanding Jamaat’s reach

Yet among Jamaat supporters – particularly younger ones – the issue is often filtered through loyalty to Rahman himself rather than doctrine.

During his recent nationwide campaign, young supporters can frequently be heard calling Shafiqur Rahman “dadu” – grandfather. White-bearded, soft-spoken and visibly attentive to supporters, Rahman fits the image.

“He connects with young people through his words,” said Abdullah Al Maruf, a Gen Z law student from Chattogram and a Jamaat supporter. “There is something about his recent work that feels like the relationship between a grandfather and his grandchildren. Where BNP leaders often belittle young people, Shafiqur speaks to them with respect.”

Maruf added that Rahman’s appeal extends beyond Jamaat’s traditional base. “Outside the usual Jamaat circle, he is more popular than previous Jamaat leaders,” he said.

Zubair, Jamaat’s assistant secretary-general, described the party’s outreach beyond traditional voters – such as the decision to nominate a Hindu candidate – not as a tactical move but one rooted in Jamaat’s constitutional framework rather than political expediency.

“Our constitution allows any Bangladeshi, regardless of religion, to be part of the party if they support our political, economic and social policies,” he said. “Supporting our religious doctrine is not a requirement for political participation.”

Jamaat leaders argue the move reflects a broader effort to shift the party’s public image – from one defined primarily by theology to one centred on governance and accountability. “We are emphasising corruption-free politics, discipline and public service,” Zubair said. “People have seen our leaders stand with them during floods, during COVID, and during the July uprising. That is why support is growing.”

Krishna Nandi, the party’s Hindu candidate from the city of Khulna, agrees. “When families fall into poverty, Jamaat-linked welfare networks step in without asking about religion or political loyalty. This culture of service explains why many citizens see Jamaat not as a party of slogans but as a party of discipline, structure and responsibility,” Nandi wrote for Al Jazeera.

The Jamaat’s outreach has also extended well beyond domestic audiences. Zubair said the party’s leadership has held meetings with Indian diplomats in Dhaka who paid a courtesy visit to Shafiqur when he was ill. Jamaat figures were invited to India’s 77th Republic Day reception at the Indian High Commission last month – an unprecedented step.

European and Western diplomats, he added, have also sought engagements with Rahman in recent months. That shift has been mirrored in Washington. In a leaked audio recording reported by The Washington Post, a US diplomat was quoted as saying American officials wanted to “be friends” with the Jamaat, asking journalists whether members of the party’s influential student wing might be willing to appear in their programmes.

As Jamaat’s international engagement expands – and as it emerges as a serious electoral force alongside frontrunner BNP – many ordinary supporters express confidence in Rahman’s leadership.

“He is a patriot,” said Abul Kalam, a voter in Rahman’s Dhaka constituency. “Whether as prime minister or opposition leader, he will lead us well.”

What lies next for the party is unclear. But analysts say that irrespective of the outcome of the elections, Rahman’s stature within Jamaat – and beyond, in Bangladesh – appears resolute.

“Shafiqur Rahman is an experienced politician and is frequently in the headlines,” Ahmad, the political historian, said. “His political thinking is not yet fully clear, but his grip over the party is evident.”