This is the annotated version of my talk at code.talks 2025 with slides, sources, and some context I didn’t get to say on stage. It’s about a question that keeps coming up in every conversation I have with engineering teams: once you have AI agents — how do you actually work with them? Not the tooling question. The organizational one.

There’s a full recording on YouTube.

Where are we, really?

Agentic engineering — where are we right now?

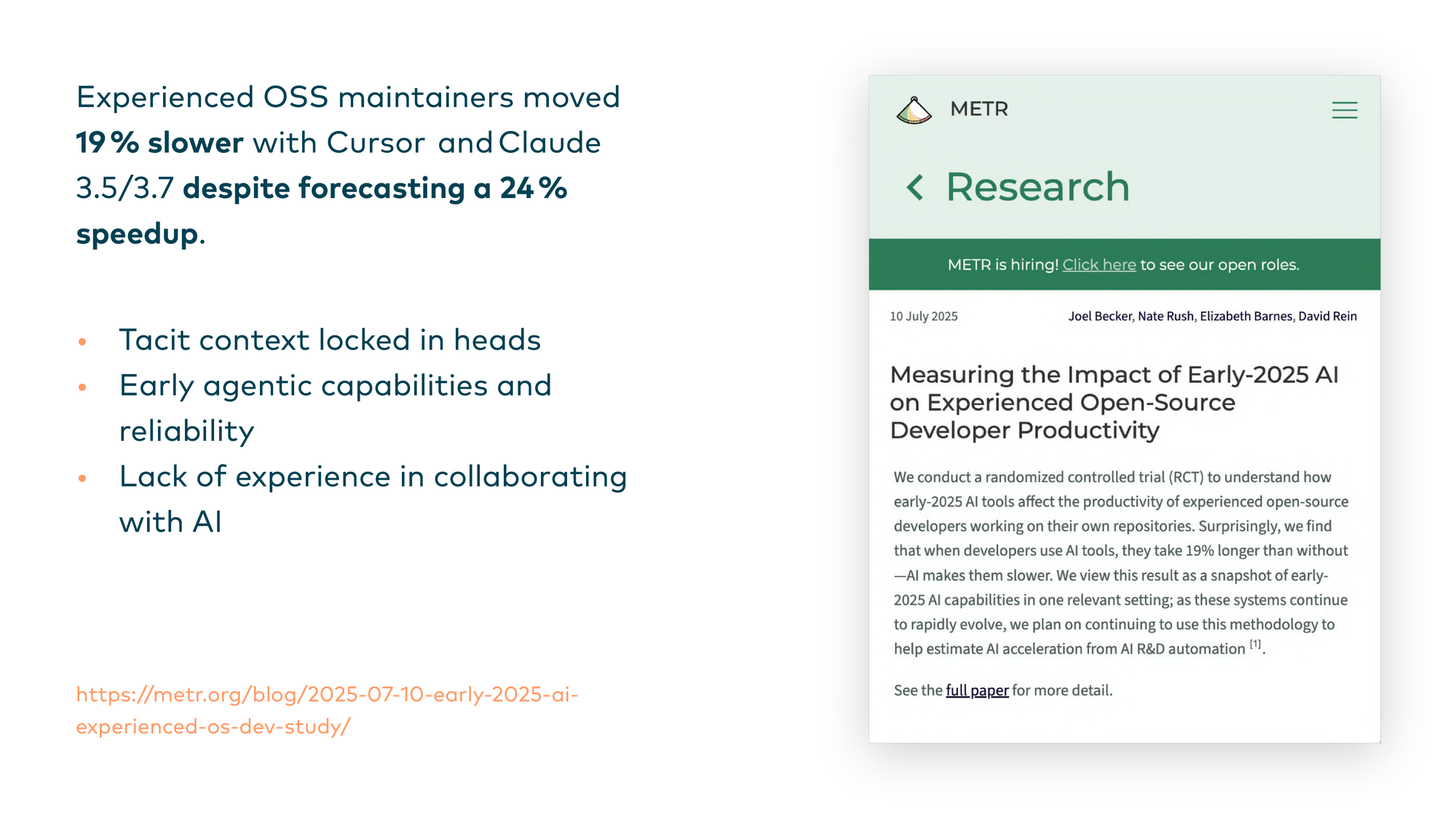

Does everyone know what METR is? It’s a publicly funded organization that analyzes state-of-the-art AI models in terms of capabilities, but also potential catastrophic issues. They ran a study with very experienced open source maintainers. These are not people who are new to programming. They are quite senior. And they gave them Cursor and Claude 3.5 — that’s what we had at the time, Stone Age — and asked them to work on their open source repositories and report what they find out. Are you getting more productive?

The maintainers forecasted a 24% speedup. They found out that on average, all of them worked 19% slower.

How can that happen? There’s no very clear answer. These were senior people, but the technology was new for them. This technology is deep. Everyone nowadays says “I get AI. I chat with ChatGPT daily. What’s the fuss about?” But it’s very opaque. And it’s very deep to master. That was a problem for even senior people in this study. The agentic capabilities weren’t where they are now.

This is the study that keeps coming up in every conversation I have with engineers. The 19% is a snapshot of early-2025 capabilities and tooling (harnesses), but the real lesson is different: mastery of agentic AI takes time. There’s no shortcut — not even for senior engineers.

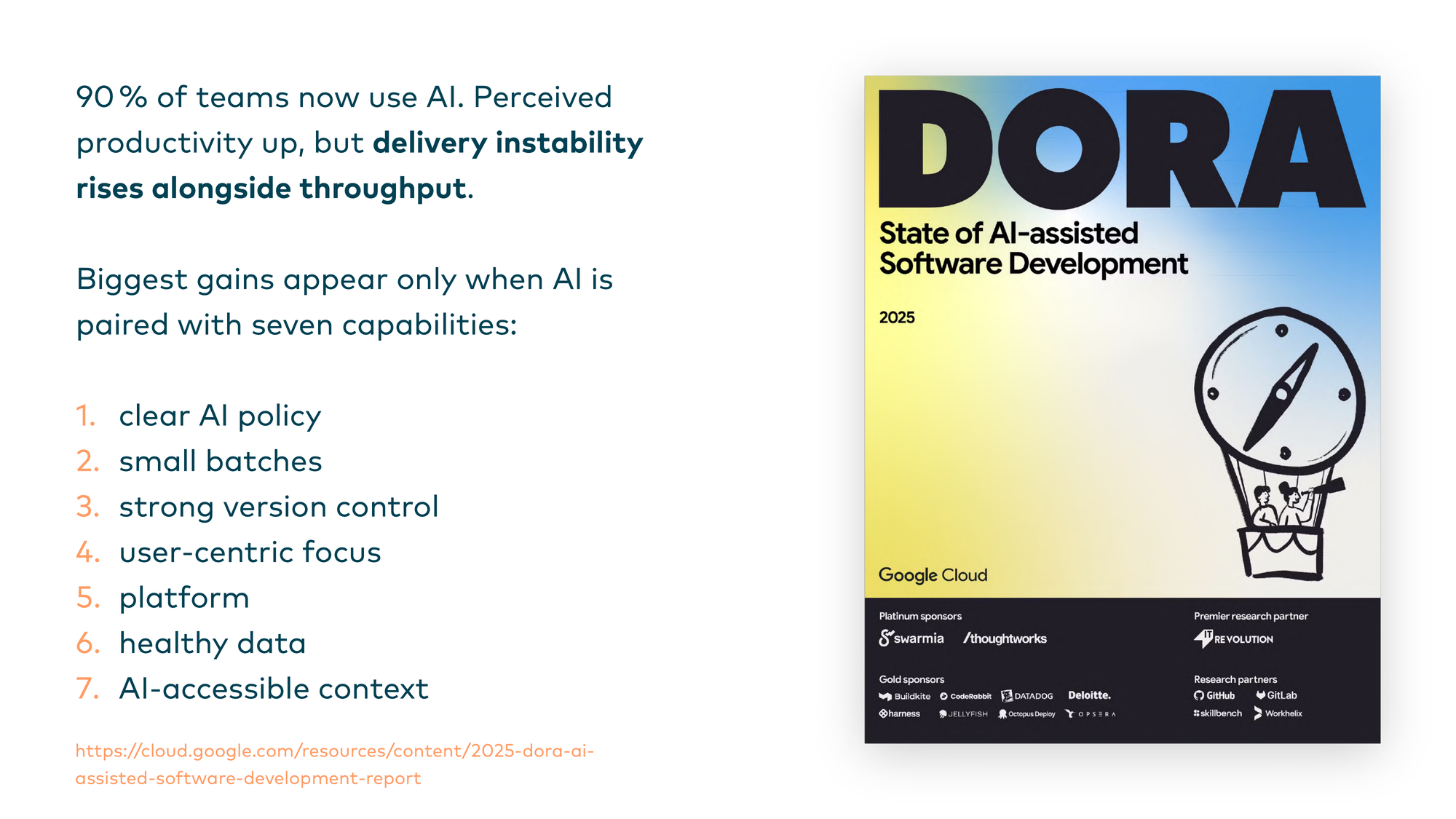

The DORA report found that 90% of teams now use AI. That’s good when it comes to adoption — but adoption is the first step. Perceived productivity is up. But instability in terms of quality arises alongside the throughput. There are way more merge requests than we ever had. The quality is not always what it’s expected to be.

And they found that the biggest gains in agentic software engineering appear only when you follow seven steps: clear AI policy, small batches, strong version control, user-centric focus, a platform for developer productivity, healthy data, and AI-accessible context.

Who has a clear AI policy? Yeah. We can step out at step one.

Then there’s DX, a company that focuses on developer experience and productivity. Their core message: structured enablement drives measurable return on investment. It’s not a tool thing. It’s not “get an Anthropic subscription, use Claude Code.” That’s the easy part.

Exponentials are hard for everyone

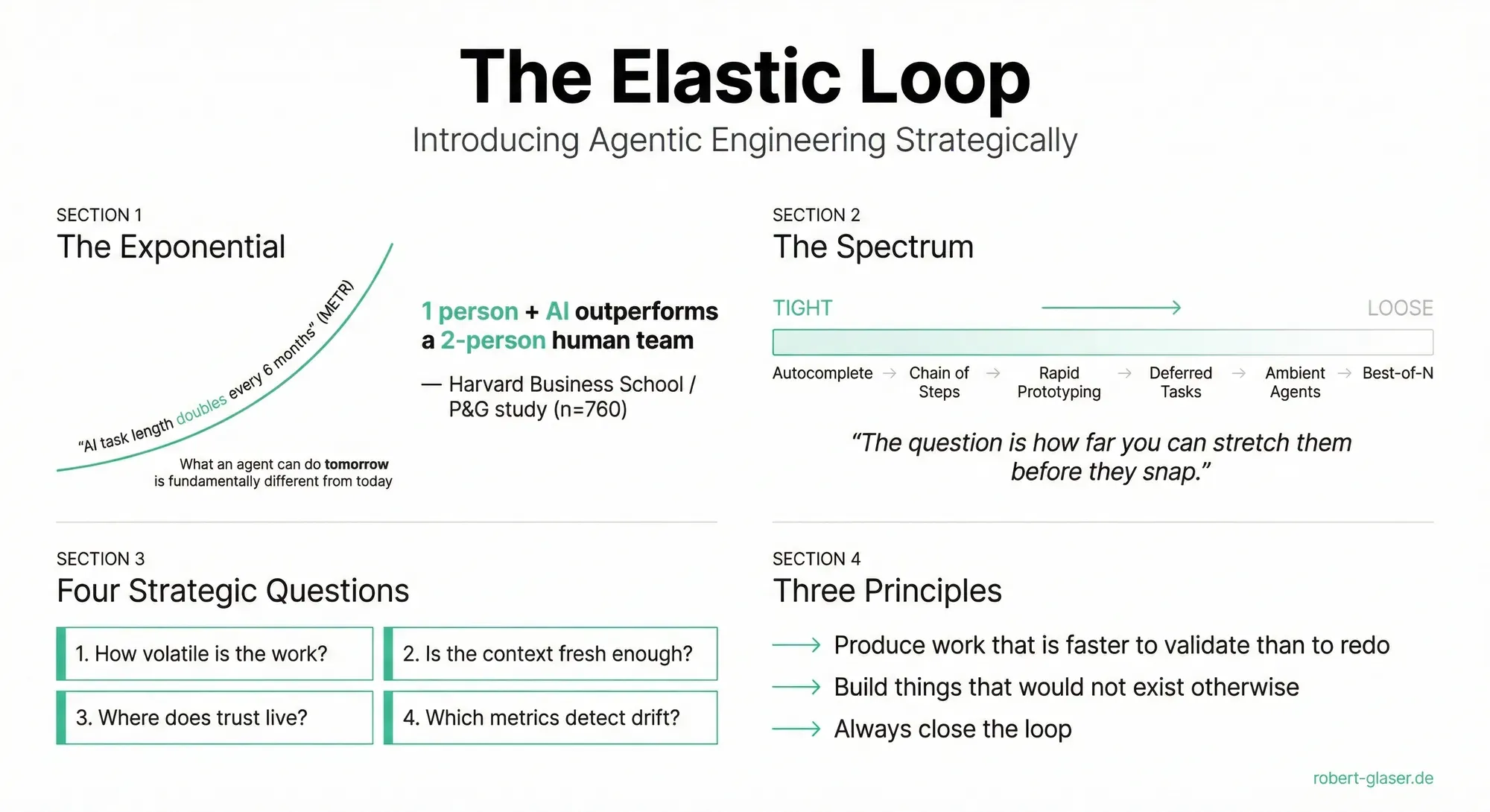

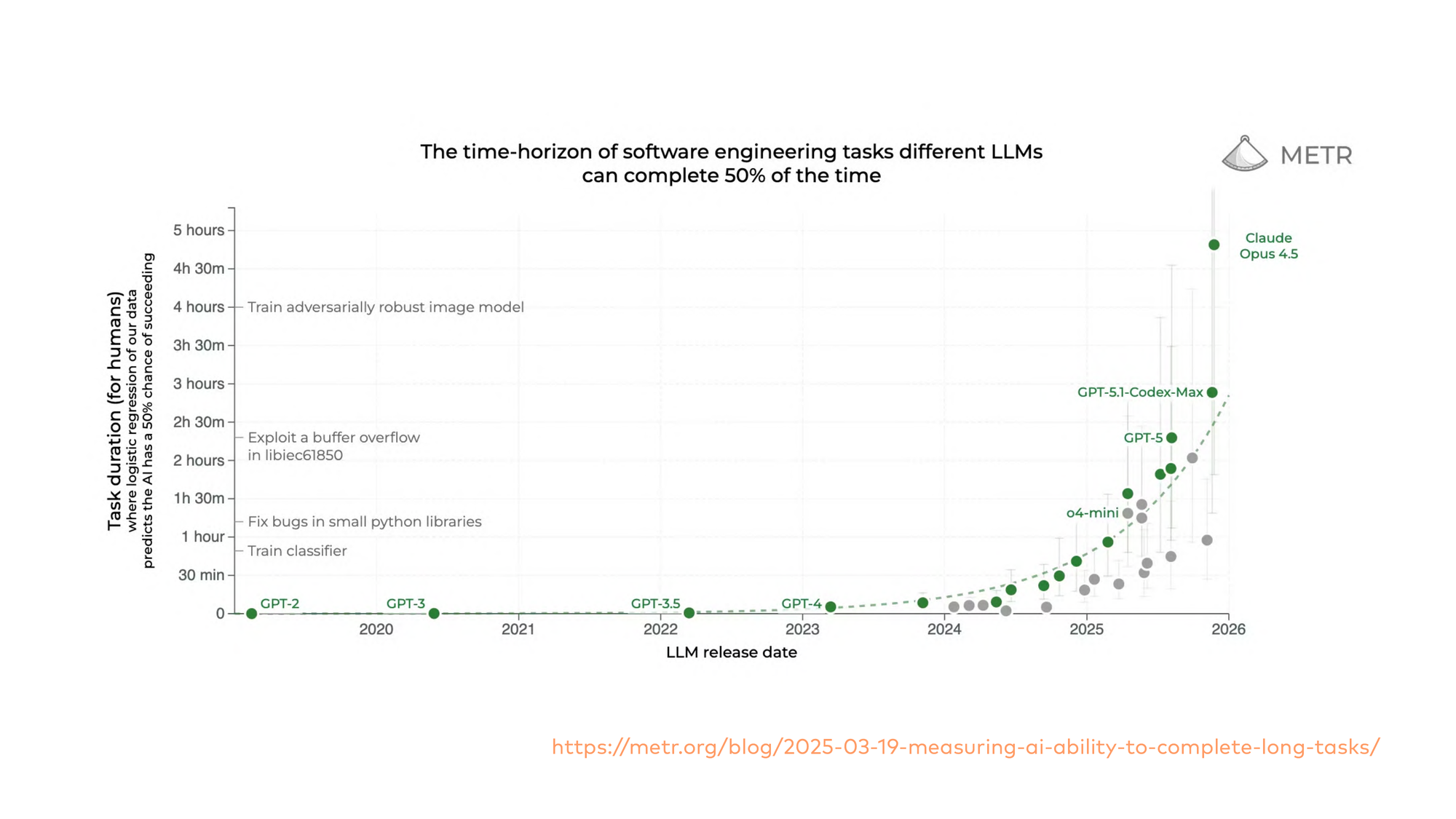

When we want to know where we’re standing right now, I always recommend looking at what the METR people are doing. They look at capabilities of state-of-the-art large language models. And we’re still on an exponential curve — the task length a state-of-the-art LLM can work on doubles every six months.

Exponentials are hard for humans to grasp. Remember COVID? “This will stay in China.” It’s very hard for us to understand what’s next year, what will be in two years.

Why is task length an important factor? Because it dictates what an agent can do. If the task length is 15 minutes, an LLM won’t do a thorough security review on a medium-sized code base. But if it goes to two hours, or twenty-four hours, or forty-eight hours — that’s where it gets interesting.

If people tell you there’s a wall — “GPT-5 responses basically sound like GPT-4.1, I don’t find it any different” — this is the capability overhang. This is a foundational technology. It’s hard to realize the advancements in capability once models crossed a certain inflection point. The task length is actually an excellent KPI to look at. See where GPT-5 is on that chart — that was a huge jump.

This basically confirms what the labs have been telling us all the time. You could say the labs invent the models, of course they have to run marketing campaigns. But they always told us: the scaling wall isn’t there. Right now we’re on a reinforcement learning scaling curve. And METR independently confirms this.

I keep coming back to this chart in customer conversations. It’s the single most useful visual to explain where we are and where we’re going. If someone tells you AI has hit a plateau — show them the task length data.

Productivity: what else is there?

When I’m talking with customers, with friends, with colleagues about agentic software engineering, everyone is talking about productivity all day long. It bores me to death.

Of course it’s a gigantic lever. But why is no one talking about things like ambition? I would never have tried to write a Rust program. Never in my life. But I can do it now. I can fix a Linux kernel driver. Never did that. But those are cases that are happening. And who measures those when people measure productivity?

Productivity itself is extremely hard to measure. It’s a very tough academic problem, and people fight over productivity measurement and ROI since forever. In my view, there isn’t a final solution. So we should look at productivity, but we should also look at ambition.

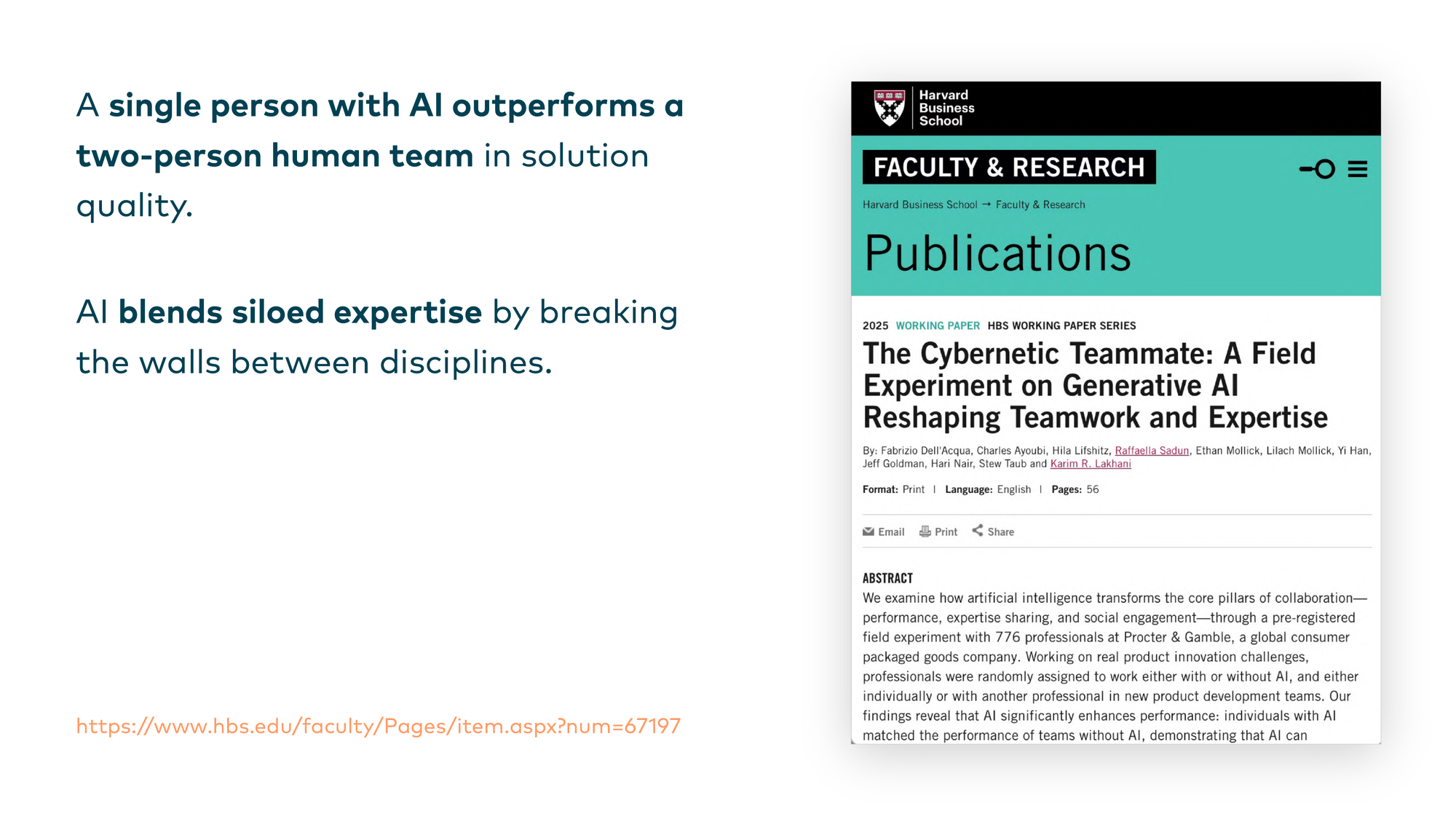

When we look at ambition and quality, there’s a very good study from Harvard Business School, ran together with Ethan Mollick and his wife. If you follow one person in AI, make it Ethan Mollick or make it Simon Willison. Or both. Don’t follow me, follow them.

They ran a study at Procter & Gamble with about 760 people over quite a long horizon. What they found: a single person with AI outperforms a two-person human team without AI. In solution quality. They tried to invent new products, new product strategies.

And they found that AI blends siloed expertise by breaking down the walls between disciplines. Salespeople had technical context without talking to a technician. Marketing people had a sales context. Engineers had a sales context. The silos blurred because there was no human gatekeeping of expertise anymore.

You don’t talk about tearing down silos when you talk about productivity. No one talks about these facets. But I find them quite interesting.

The “Cybernetic Teammate” paper is one of the most underrated AI studies out there. It’s not about engineering at all — it’s about how AI transforms collaboration across functions. The silo-blending effect is something I see in organizations I work with, where adoption has moved beyond the tooling phase.

The mirror

What happens right now is that every company wants to buy agents, onboard agents. I’m hearing from a lot of customers where big consulting engages in placing four monolithic agents in the organization. “We’ll set you up a marketing agent, a sales agent, and a big developer agent for your whole development department.” Sounds like a good idea, right?

What it comes down to: what is the organization supposed to do with those agents?

Working with AI — even non-agentic — is very hard to grasp, as it’s such an opaque technology. It requires a lot of experience. When you have an agent, it multiplies the problem. Agentic AI is an amplifier of strengths but also of weaknesses. Essentially, it’s a mirror of your organization. If your organization is faulty, broken in some ways — no organization is perfect — it will mirror that.

Ask yourself: what does the mirror in your organization currently reflect? Bad policies? A weird quality control procedure? Trust issues? “Merge requests by juniors cannot be trusted.” Stuff like that happens in all organizations.

It comes down to this: don’t treat AI like a tool you can buy. You can buy AI as a subscription — it’s a commodity technology now, basically like a liquid you pay for by volume. But when your company needs that liquid to function, to do work, you’ve got to lay pipes. Have cups, measurement devices, tanks. It’s like electricity.

When people tell me “we ran a workshop and found out we don’t have AI use cases” — of course you do. Everyone has AI use cases. What you have is a focusing problem. “We’ll do summarization of marketing reports.” Okay, you can use AI for that. But what about the robotic arm in your basement? Think bigger. That’s the actual problem.

Enter the elastic loop

If you want to embrace agentic AI as an organization, it comes down to: how can you use it iteratively, in loops? Remember the agile manifesto?

What we’re seeing — at customers, at our own company — is that when you work with AI agents, you work in loops. There’s a tight loop, and there are bigger, looser loops.

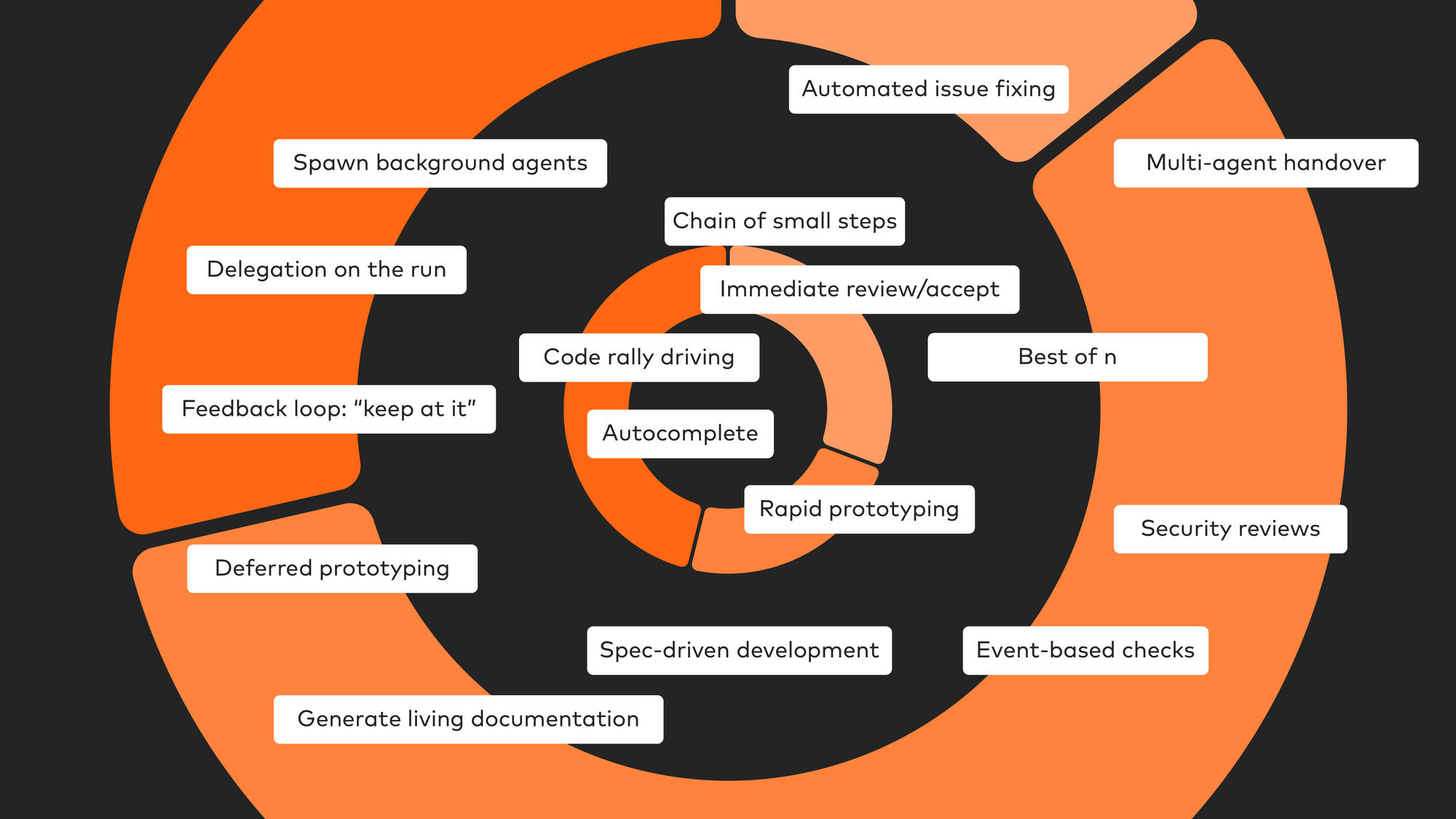

Autocomplete is maybe the tightest form of any loop. You’re sitting in VS Code, it makes suggestions, you press tab, you close the loop. Or you press escape, reject the suggestion, and close the loop.

But agentic AI is so much more than autocomplete.

On the tighter end of the spectrum: rapid prototyping. A colleague of mine who’s a product owner skips Figma nowadays. She does everything with Claude Code — prototypes for customers as actual software, with the actual UI. She shows it to the customer, gets feedback, closes the loop.

Chain of small steps — do this, enter, no that wasn’t good, do it the other way. A very tight feedback loop you’re giving the agent.

And there’s so much more. When I’m walking the dog, I sometimes have ideas — it’s nowadays quicker to hand it to Codex for implementing it async than to write a note on my phone. Of course I won’t use it in production. Hopefully. But getting ideas formed into actual software while walking the dog — this is new. And this is a looser loop.

Deferred prototyping, living documentation, security reviews, best-of-n — implement this feature in five different ways. We can do that now. Code is not scarce anymore. But we’re still treating this technology like “you do this, no, do it the other way.” What about implementing it in five different ways?

In some cases, it shifts the problem — someone has to look at it afterwards. But that’s where I’m going. It’s a skill we have to develop. It’s a lot about intuition and experience. We have to build it.

Feedback loops all the way down

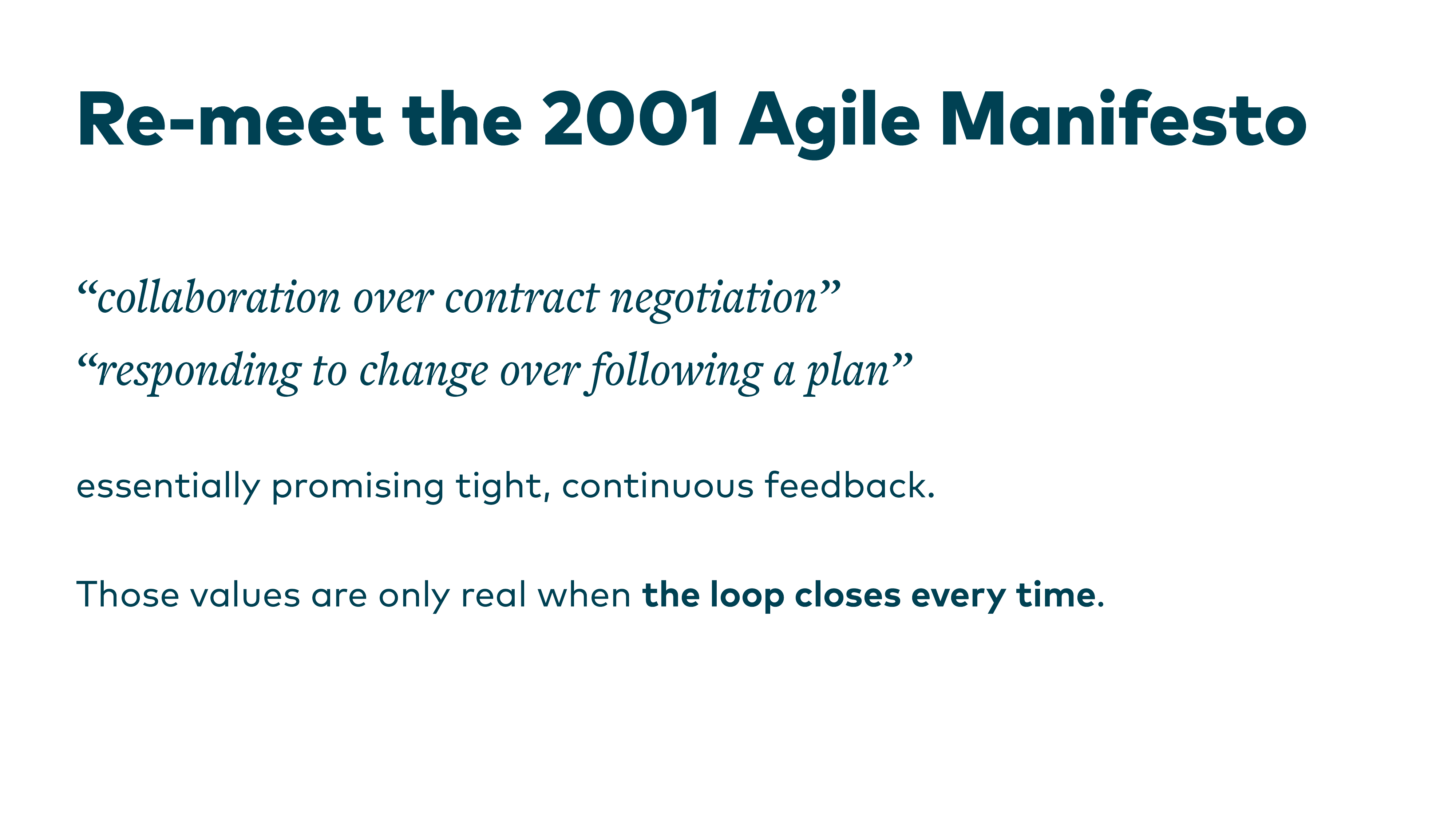

Let’s re-meet the agile manifesto. What did it actually say? It didn’t say you have to do daily stand-ups. It didn’t say anything about sprint plannings. It didn’t say anything about Scrum — that’s what we invented. Retros, demos. It was basically all about feedback loops and collaboration.

When we think about how to work with agentic AI, we can go back to old things and they can help us. You need continuous feedback. If your agent doesn’t get feedback — a successful test run, a build, you correcting it — you have to close the loop. If you don’t close the loop, you’re basically randomizing it.

But you don’t want to close the loop on a very tight loop all the time — that doesn’t scale. You have to find a way where entering a looser loop is still okay. But make sure to close it every time.

This is the core insight of the whole talk: the agile manifesto was always about feedback loops. Agentic AI doesn’t change that principle — it stretches the loops. The question is how far you can stretch them before they snap.

Tight versus loose

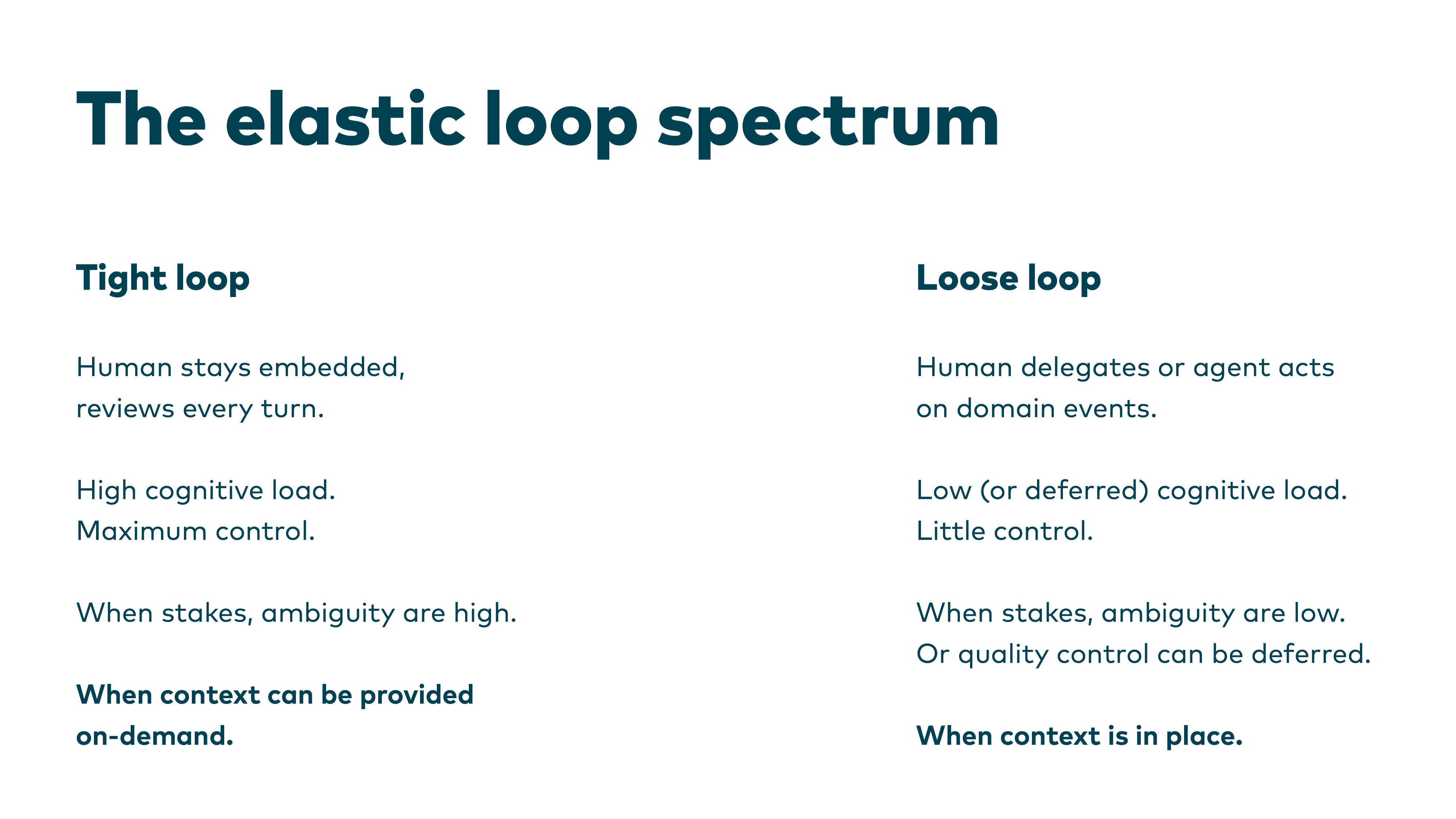

There’s a spectrum. On the left side: a very tight loop. Autocomplete or chain of small steps. The human stays embedded, reviews every turn. High cognitive load — you’ve got to be focused. You can’t do this with four agents in parallel. Maybe some of you can. I can’t.

It’s high cognitive load, but it offers maximum control. You don’t need maximum control all the time. When stakes are high and ambiguity is high and you can’t tell the agent exactly what to do — choose a tight loop. When you’re able to provide context on demand — you’re sitting right there — be able to give it.

The other end of the spectrum: the loose loop. You delegate, you defer. Or the agent just listens in the background — ambient agents. For domain events. A new issue gets created with the tag “agent.” Agent watches, implements it, does a review. Or your product person (hello, Silos) watches a folder where user interviews are placed, analyzes them, proposes experiments for new features. You don’t have to be there. You can do it async, on a loose loop. But make sure context is in place.

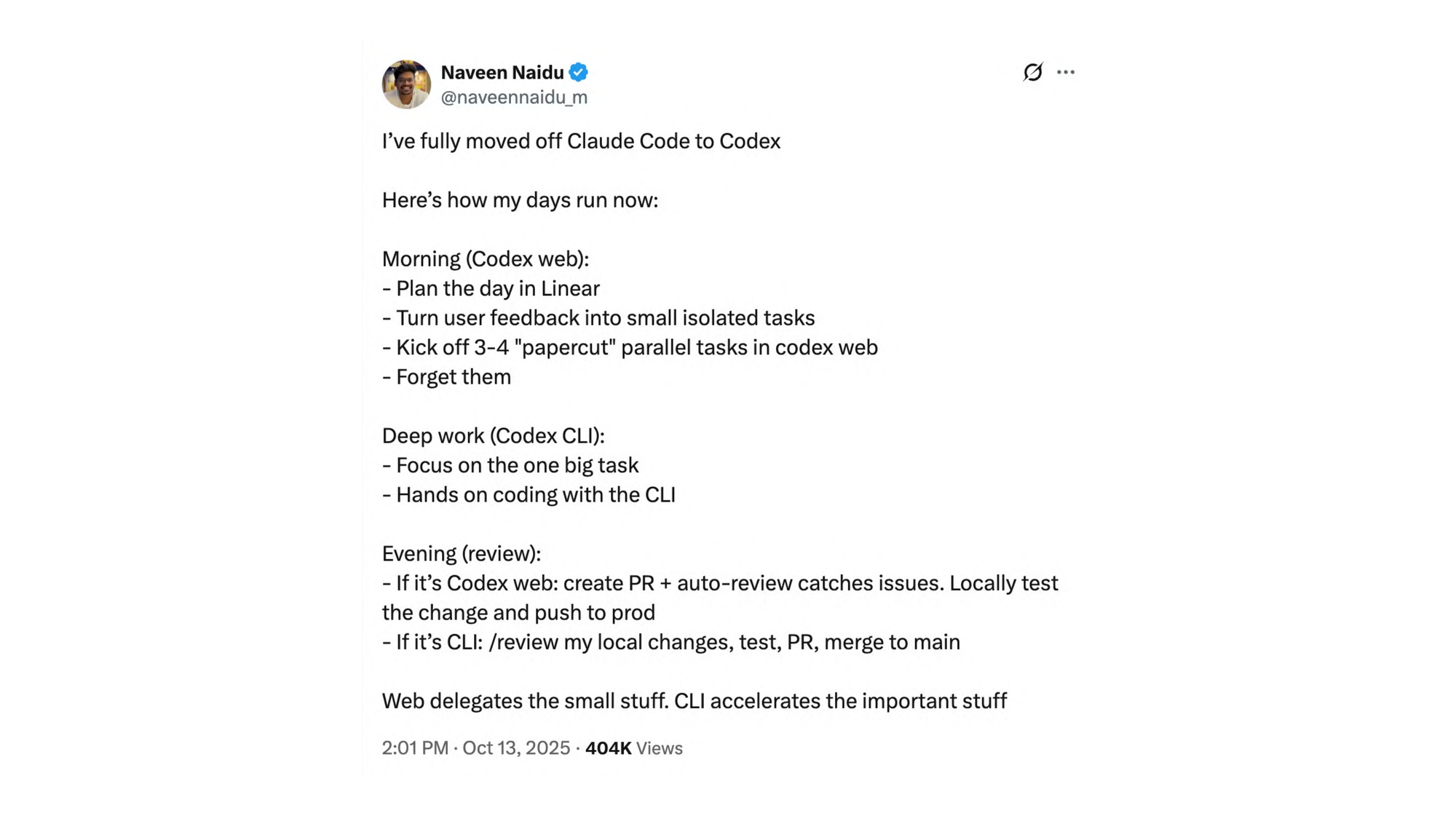

I saw this on X and the interesting part isn’t the tool — I don’t want to engage in any Claude Code versus Codex fight. The interesting part is how this person works. He goes into Codex in the morning, plans the day in Linear, takes user feedback and kicks off an async agent on three to four paper cuts. Small steps, small tries at a bug fix, whatever. And then he forgets it.

Then he enters the tight loop. Deep work, sitting there every turn, engaging in very important, high-risk stuff.

In the evening, he goes back. The paper cuts have been implemented — sometimes with an auto-review. Basically four merge requests to review, at a time when he maybe drained a lot of energy in the deep work session.

Everyone works differently. That’s totally okay. But what he’s doing right is: he uses different loop sizes, and he makes sure they’re closed.

Four strategic questions

So we need to figure out: when to tighten and when to relax the loop? I brought some strategic questions. Not many answers.

How volatile is the thing you’re working on? Is it a credit insurance formula? That’s high-risk stuff — choose a tighter loop. Is it something that wouldn’t exist otherwise? Choose a loose loop.

What’s the freshness of the context? Is the context good enough? Can you provide it on demand? “I forgot to tell you, we do it this way” — choose a tighter loop. If the context is already in place — choose a looser one.

Where does trust in your organization live? That’s a hard question. Some people tell me “we have peer reviews, everyone who implements a feature needs a merge request review.” And I’m like — that’s great, but is that how you define trust? That’s a tactic, not a strategy.

If your organization doesn’t trust you to enter loose loops — to produce stuff you won’t look at line by line — people will always resort to tight loops. Because they’re not feeling trusted to do otherwise.

Which metrics detect drift in your loops? What’s your lead time for new features? Your fail rate? Don’t count merged merge requests — that’s not a KPI, that’s a number. Every organization has more of them now.

What’s interesting is: how many merge requests haven’t been closed? Are getting stale? How many terminal sessions have been discarded by an angry user? That’s what you want to look at. Unclosed loops.

The trust question is the one that makes rooms go quiet. Most organizations have never articulated where trust actually lives. When I ask “is it okay to ship agent-written code that replaces an Excel table nobody ever reviewed?” — the silence tells me everything.

Build taste

Who knows how truffle tastes? There’s this famous saying, I think I heard it from Anthony Bourdain — truffle tastes like a bike accident in the woods.

The metaphor: truffle is like agentic AI. On the surface, it’s just a mushroom. But truffle doesn’t taste like a mushroom. It’s very complex. Some people say earthy, wooden, minty, chocolatey — but it’s hard to describe. People need to build intuition.

You can’t describe complex food when you’re new to food. But your people, your teams, have to develop a taste for AI. Otherwise they’ll say: let’s skip it, it’s too deep, too complex. Or they keep treating it as a stochastic parrot.

This is a weird new situation for all of us. Everyone I talk to about this — it’s weird for me too. But we have to build taste and intuition. And as a bonus: for a technology that doubles in capabilities every six months. That’s stressful. AI puts a lot of stress on organizations, on companies, on individuals.

But I don’t think it’s an option to say “let’s wait it out, it will blow over.” The genie’s out of the bottle.

“I’m beginning to suspect that a key skill in working effectively with coding agents is developing an intuition for when you don’t need to closely review every line of code they produce. This feels deeply uncomfortable!”

— Simon Willison

Simon Willison. He’s the creator of the Django Python framework. Nowadays he works a lot with large language models, develops software, and documents nearly every day what he learns. He’s a good writer — not hyper-technical, but rigorous. I learned so much by reading him.

And he was skeptical. He always sat in the tight loop — “I want to see every line, it makes me so much more productive, but I want to check every line.” And then, after four months, he said this. It feels uncomfortable. He can’t articulate it any better. But he’s developing a feeling, a taste, that he doesn’t need to review every line anymore.

When loops don’t close

What are examples for unclosed loops?

Drive-by prompting. Roll down the window, shoot at Claude Code — “build me this.” Everyone did it. I did it. Agent has to prime itself, codebase doesn’t offer enough context, unhappy developer quits the tight loop.

Papercut best-of-n development. Tasks delegated to background agents, never reviewed. The selection process never happens. Not in the evening. Not ever.

Ambient agent opens a refactoring PR. Engineering never reviews it. Change decays behind main — improvements, rewards, and learnings are all lost.

Product Discovery Agent clusters user feedback and proposes experiments. Yet product never validates them with customers.

You can do anything. But you have to close the loop — tight or loose.

Everything in agentic engineering comes down to three things:

- Produce work that’s faster to validate than to redo. Otherwise it doesn’t make sense.

- Build things that would not exist otherwise. Ditch the Excel table people are fiddling with. In which sprint planning would the team say “let’s pull that thing sitting at the bottom of the backlog for three years”? Won’t happen. But you can do it now, on the side.

- Always close the loop.

I think about number two a lot. The most valuable things agents produce aren’t only faster versions of what we already build — they’re the things nobody would have tackled. The internal tool nobody had time for. The documentation nobody would write. The experiment nobody would run. The production bug nobody would fix.

The age of the agent orchestrator

I think we’re living in the age of the agent orchestrator. What does that mean for your teams, for your people, for skill development?

Markets tend to organize around whatever is in short supply. It’s an economic constant. Expertise will get democratized. Embrace it. But experience does not. Not right now.

It’s important for you to have experience, to earn experience, to build it. But don’t base your career solely on your hands’ work. Base it on your head’s work — because the work you do with your hands will get way cheaper. Markets won’t circle around your hands’ works anymore.

It’s not always about code that looks like John Carmack wrote it. Sometimes it’s okay to engage in a loose loop.

There will still be experts. You will still be experts. But the baseline skill we have to develop is: provide judgment, set high-level strategy, and handle the weird cases. That’s what you will need humans for.

Knowing how to break down a task, set a reward, audit a run — remember reinforcement learning? That’s a skill we have to learn. Some say it’s a skill every developer always had to have. Even before AI.

Culture, agency, and teams

Your organization’s culture eats your strategy. You can make the biggest strategic plans. But if you don’t create an environment where people are comfortable engaging in loose loops, building stuff they don’t have a mandate for — you miss out.

How do you delegate? What kind of feedback culture and agency do you need?

You need to surface cultural blockers and tackle them. Fear of loss of control — sometimes we see engineers in our trainings who want to read every message Claude Code writes. They want to understand it to the letter because they have a deep fear of losing control.

Shallow feedback rituals. Limited experiential trust — if your developers don’t build experience in shipping actual software with agents, they’ll always resort to tight loops.

It is simply impossible not to see the reality of what is happening. Writing code is no longer needed for the most part. It is now a lot more interesting to understand what to do, and how to do it (and, about this second part, LLMs are great partners, too).

— Salvatore Sanfilippo (antirez), creator of Redis

You need to change minds. It’s not our hands’ work we’re here for — it’s our heads’ work. And hand skills have become multitudes cheaper in the last two years. They will continue to, by the day.

Orgs that have worked out how to empower autonomous groups of humans […] are already in the best place to use agentic AI.

— Matthew Skelton, co-author of Team Topologies

You need to enable autonomy. Build a sky for people to fly in. A lot of companies have set teams up with huge amounts of autonomy — people are free to engage. But no one engages. Why?

Not all people can or like to deal with an overly big amount of autonomy. That’s where agency comes in. Agency is the ability to make use of autonomy. If your people are not agentic — see the parallel — they won’t use the autonomy you give them. You can bury them in autonomy. They won’t embrace it.

High-agency people take risks. They’re willing to burn their fingers trying new stuff, engaging in loose loops.

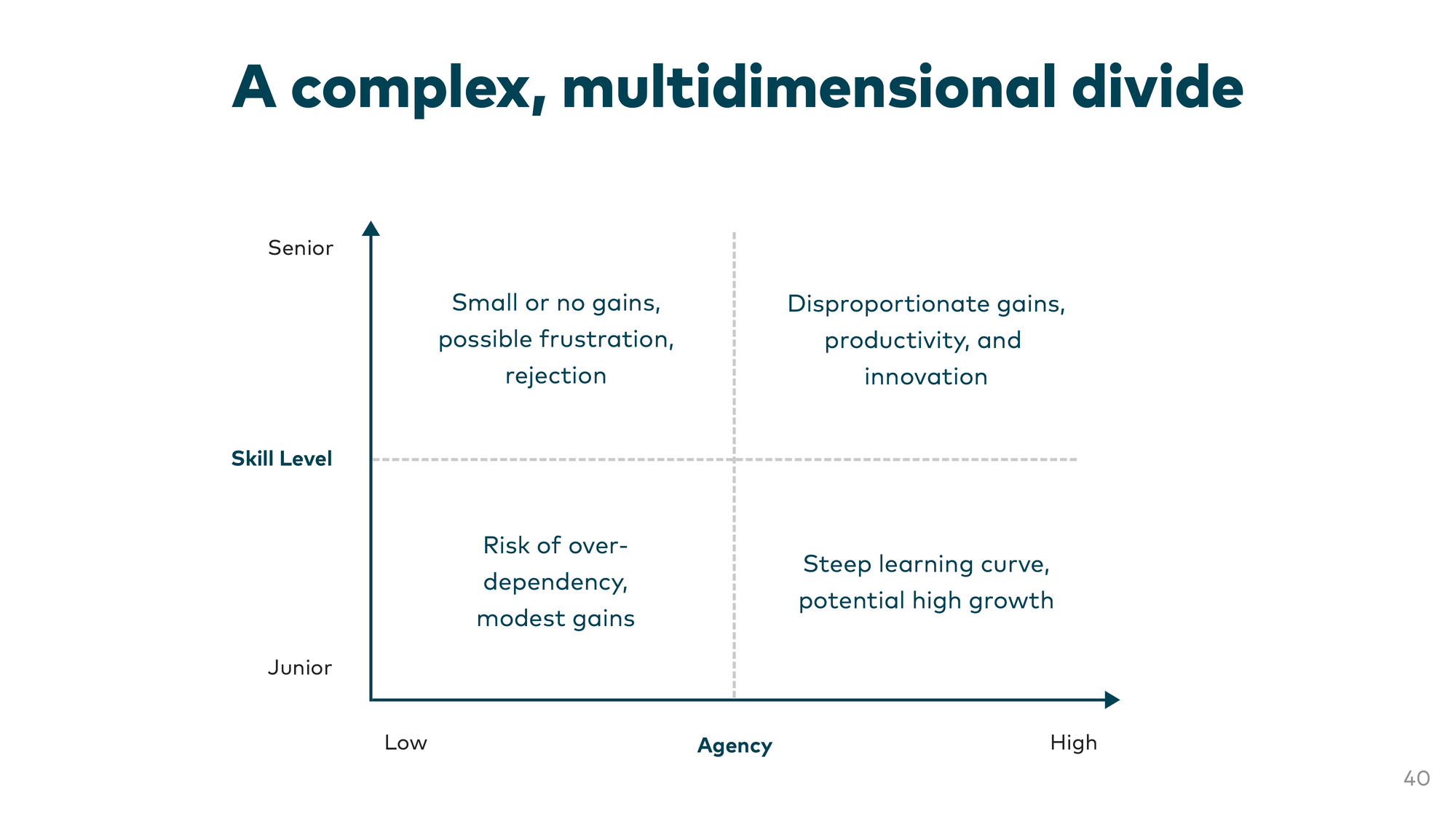

Some people talk about a great divide. Benefits aren’t distributed equally — high-agency engineers see outsized gains. But it comes down to two axes: skill level and agency. You can’t say juniors are bad for agentic engineering or seniors are by definition good.

How do you enable agency? Build ladders. Don’t force personalities to flip. Drop people into safe loops, let them earn experience so they can risk more the next day. Codify playbooks, remove guesswork. Reward ownership and accountability. Run agency labs — tackle real problems, immediately reflect on what closed the loops.

Rebuild your teams around agency. What we’re seeing in customer projects where teams use agents all day: they step on each other’s feet. I don’t think it works anymore to have a team with a UX designer, UI designer, product owner, and five developers. Maybe it’ll be one developer. Because you constantly have to align yourself — “Can I get in your way with my agent? Oh no, I’m parking there right now. I have two agents working in the same area.” It’s a mess.

One accountable owner per discipline. Every duplicate role adds handoffs, waiting, and alignment drag — exactly the friction that erases the leverage you’re trying to buy.

The team structure question is the one that scares people most. It sounds like I’m saying “fire four developers.” I’m not. I’m saying the shape of teams will change, and we need to think about it now.

Tactics for closed loops

I want to close this talk with tactics, not only strategy.

Three things — they’re not the whole picture, but they’re a start:

Agent-ready environments. Standardize reproducible sandboxes and ephemeral stacks so agents can execute, test, and observe work without manual setup.

Shareable agent skills. Codify company knowledge, workflows, and deterministic tooling as reusable, model-agnostic agent skills.

Instrument loop telemetry. This is the most important one. Build something that triggers a signal: this loop hasn’t been closed. User quit the session, was angry. Bake feedback-loop IDs into CI/CD, testing, and review tools so every delegation emits start/stop, drift alerts, and human interventions. You won’t learn otherwise. Learnings will vanish.

Why do we have lots of open loose loops? Was there less context? Did people feel unsure if they could merge? What was the problem? You will never learn unless you instrument it.

And: don’t use merged PRs as a success metric.

Most of what I described here isn’t new — it’s software engineering practices we’ve known for decades. Writing requirements, test-first, environments. The difference is that these practices now provide feedback to both us and the agents. If your feedback loops are open, agentic engineering won’t work well.

Wrapping up

Three things to tackle:

- Map where your loops don’t close. Where do agents produce work that nobody validates? Where do developers give up on tight loops because context is missing?

- Enable agency. This is the hard part of the three. Build the environment where people are comfortable stretching into looser loops.

- Instrument. Measure unclosed loops, not merged PRs. Learn why loops break — then fix the system, not the people.

At some point in my life I want to write an O’Reilly book. Maybe it will be this.

This talk was given at code.talks 2025 in Hamburg on January 14, 2025. The recording is linked above. If you’d like to discuss any of this — or need help figuring out where your loops don’t close — let’s talk.