Policy responses to stranded asset risks

In any of these scenarios, targeted policy intervention is essential, including support for debt and asset depreciation management, and general transition assistance for farmers. A socially just transition that addresses existing social and economic inequalities and vulnerabilities within the food system is crucial to ensure that transition costs and benefits are equitably distributed, ultimately fostering greater public support for the transition21,22,23.

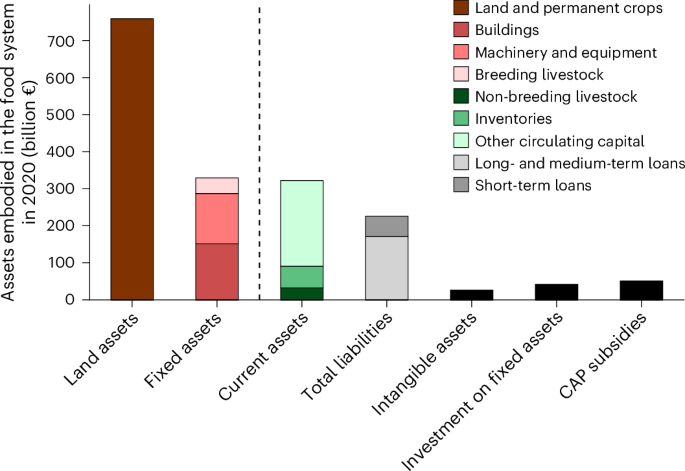

While the general need for a well-managed transition is widely acknowledged23, the quantification of stranded asset risks, €61 billion, €168 billion and €255 billion under the moderate, low and zero ASF scenarios, adds crucial specificity for policy design. By translating abstract transition risks into concrete financial terms, such figures can guide the scale and timing of depreciation support, inform compensation schemes and support realistic regulatory timelines. Our analysis also provides asset intensity per kilogram of food for different food items (Fig. 2), offering a basis for tailoring compensation and support mechanisms according to food-level exposure. Similar approaches are already used in the energy sector, where compensation for stranded coal assets or displaced workers is estimated per MW or per worker to support labour reskilling and regional diversification24,25,26.

The EU’s Just Transition Mechanism, established under the Green Deal, allocates ~€55 billion to support social and economic adjustments in high-carbon regions27. Although the mechanism does not currently cover agriculture, the European Economic and Social Committee has called for a dedicated just transition framework for the agrifood sector, an idea under consideration in the CAP post-2027 reform28. Without targeted support, high stranded asset exposure, especially in bovine, pig meat and dairy systems, may delay EU dietary and climate action by increasing political resistance or financial vulnerability among producers19. Our analysis helps identify where such friction is likely and the scale of the issue that policy levers, such as aligning depreciation schedules, reforming agricultural subsidies or providing liquidity support, can help address, reduce resistance and enable more rapid transformation.

Whereas some asset stranding may be unavoidable under a transition away from ASFs and in response to the climate crisis, the key policy challenge lies in determining when, where and how these costs arise, along with, importantly, how they are distributed. At the farm level, stranded assets pose direct financial risks to farmers, particularly those with high sunk costs or long investment cycles and limited liquidity, who may face loan defaults or business failure if transition support is inadequate10. Financial risk is further amplified by short-term decision-making incentives and path dependency, leaving farmers with few viable exit strategies without public support10. When such constraints are widespread across Europe, they inhibit the reallocation of land, labour and capital towards plant-based production systems, creating system-level delays even when such pathways are technically and economically feasible.

In this context, CAP reforms are critical, as current agricultural subsidies may inadvertently contribute to stranded assets by incentivizing investment in specific practices or crops that are not aligned with environmental priorities, evolving market demands and climate risks29. For example, livestock-specific subsidies encourage investments that risk becoming stranded if consumer preferences shift towards more plant-rich diets or if climate change makes livestock production economically inviable8,10. Redirecting CAP budgets away from ASFs and towards repurposing support, liquidity assistance and crop production is one of the clearest policy levers to weaken existing ASF lock-ins, which are system-wide but may materialize through farm-level decisions, and to reduce transition delays.

Assets may be repurposed for alternative uses, with emerging opportunities in plant-based agriculture, such as precision farming, alternative protein production and regenerative farming. Examples include converting chicken sheds, dairy barns and pig barns into facilities for growing mushrooms, hemp, microgreens and specialty vegetables and herbs30,31. Besides the building structure itself, existing infrastructure such as cooling cells, feeders, watering systems and computer systems, can often be repurposed to support greenhouse operations30. In addition, retrofitting infrastructure beyond the farm gate, particularly in the manufacturing sector, presents a capital-efficient strategy for rapidly scaling up production capacity for plant-based proteins32. There may also be opportunities for repurposing assets for other sectors, especially with respect to buildings, energy generation, tourism and more. Whereas our results show that potential ASF-related losses far outweigh gains in plant-based assets, we do not assess whether these gains reflect new or repurposed assets. Further research can target the effects of partial offsets when evaluating transition costs and mitigation opportunities at the farm level.

From a climate perspective, failure to transition away from ASF production and consumption could exacerbate asset stranding risks as climate impacts on agriculture intensify. Both a faster decarbonization and more severe impacts of climate change could drive higher levels of asset stranding, increasing the chances of economic, social and political repercussions16. Additionally, low-animal welfare practices, combined with climate risks, may increase the likelihood of zoonotic and epizootic events within livestock populations33. Whereas stronger regulatory responses to animal welfare and biosecurity concerns could help mitigate disease risks, they would also accelerate asset stranding, especially in intensive, high-risk animal agriculture systems34.

Despite uncertainties surrounding transition pathways, the inertia of the climate system guarantees that even if greenhouse gas emissions were halted immediately, the risks of asset stranding in the food system would continue to grow16. Climate change is probably already contributing to agricultural asset stranding by driving extreme weather, altering water supplies and negatively impacting crop yields and the growth of dairy, meat and fish stocks16,17. Adaptive food governance is therefore essential, including diversification of agricultural production, investment in sustainable farming practices and transition support for farmers adapting to new market conditions8. However, while such strategies can mitigate some physical risks from climate change, they are unlikely to address all potential sources of asset stranding16.

Meanwhile, investors currently favour on-farm climate solutions, such as regenerative agriculture and feed additives, over demand-side measures such as promoting plant-based diets35. This emphasizes the need for policy interventions that encourage transitions towards more plant-based diets, for instance, through measures supporting livestock reductions36 and promoting plant-based alternatives37,38. Given the uncertainties surrounding the efficacy of on-farm livestock solutions and their limited capacity to address broader environmental harms3,39, investors should take a more proactive role. Rather than viewing at-risk assets solely as financial exposure to be managed, they must support the deliberate phase-out of a large proportion of ASF infrastructure through transition finance, helping to avoid prolonged lock-in and enabling a more rapid food system transformation19.

Systemic and downstream repercussions

The interconnected nature of the food system, characterized by strong investment synergies across different asset types, means that stranding can propagate through supply chains10. The stranding of physical assets such as farm buildings, irrigation systems and crop fields can have cascading impacts across food supply chains, affecting other assets such as business networks and cooperatives reliant on consistent agricultural production. These disruptions may destabilize local communities and erode intangible assets such as knowledge, social capital and place-based expertise, elements often undervalued in financial accounting, but difficult to restore once lost10. This underscores the need for responses that go beyond financial risk management but that also consider the broader social impacts of asset stranding16.

The effects of stranded agricultural assets extend beyond primary production, leading to cascading impacts across multiple sectors8,17. For example, food processing facilities producing animal by-products such as leather and casein may experience supply constraints38, whereas logistics companies could face underutilization of refrigerated trucks and live animal transport infrastructure. Retailers may need to repurpose meat-focussed display areas and ASF-focussed financial institutes could see declines in the collateral value of loans tied to livestock assets. Those in the pharmaceutical industry that are heavily reliant on animal agriculture for antibiotic sales40, would experience reduced demand, affecting upstream supply chains, research and investments. In regions where tourism is closely linked to animal agriculture, revenue losses could result in additional asset stranding.

As the food system transitions towards plant-sourced foods, assets will shift, but their location, concentration and size will be naturally very different, creating new vulnerabilities and opportunities. Our stranded asset calculations may underestimate these broader, cascading risks in infrastructure beyond direct food production, such as transportation, storage facilities, electrification and other on-farm resources. It also does not account for asset stranding outside the European Union and UK, even though global markets are deeply interconnected.

Farmers remain particularly vulnerable in this transition due to their limited profitability across many areas of the EU + UK and high degree of lock-in from long-term investments22,41. In a food system where economic power is largely concentrated among manufacturers and retailers, farmers’ capacity to adapt to dietary shifts is restricted. This reinforces the need for broad governmental action to reorganize support mechanisms and ensure a just transition through targeted agricultural policies21,22,23,38,41, informed by quantified stranded asset risks in the livestock and feed systems.