How do you ship consistent, high-performance mobile UIs across iOS, Android, and Web – without slowing your teams down? For us at

Allegro, this question quickly became a daily reality, forcing constant trade-offs between performance and iteration speed, native

quality and cross-platform reach, flexibility and long-term maintainability. Along the way, it led us from our own internal solutions to an unexpected

open-source challenger — and to rethinking how we build mobile interfaces at scale.

More than six years ago we built MBox, our in-house Server-Driven UI solution. It has served

us well, enabling rapid experimentation and flexible UI updates without having to ship a new app version every time.

But over time we started asking ourselves an important question: what’s next?

As the ecosystem evolved, so did the expectations. We began exploring alternatives to our internal technology stack, looking for solutions that could offer the

best of both worlds: the speed and flexibility of server-driven UI, combined with truly native performance and a modern developer experience.

That search led us to Lynx – a recently released, open-source cross-platform framework designed around native rendering. According to its

authors, Lynx delivers better performance, reduced latency, and an improved user experience by avoiding the common bottlenecks of purely web-based rendering

approaches. Even more interestingly, it enables rendering the same content across three platforms (iOS, Android, and Web) using a single React codebase.

On paper, it looked too good to ignore.

What really caught our attention was how closely Lynx aligned with what we had already been building internally for years and how boldly it promised to go

beyond. Out of the box, Lynx already provides many of the capabilities we consider critical, including:

- Native rendering,

- Cross-platform development,

- Server-driven UI support,

- Deep integration with the React ecosystem.

In other words, it didn’t feel like just another framework worth benchmarking. It looked like a potential accelerator for our long-term direction. Lynx supports

server-driven UI, can be integrated with our content management system Opbox, and could potentially operate similarly to MBox but with a significantly broader feature

set: full JavaScript support, animations, advanced CSS, complex layouts, and more.

And the best part? It delivered most of the functionality we needed straight out of the box, with virtually no initial investment.

So we did what we always do when we find a promising technology: we battle-tested it.

Allegro background #

The Allegro mobile app is developed natively on both iOS and Android, and its UI is built as a hybrid of fully native screens, screens rendered via MBox and

WebView.

MBox has been particularly effective for content-oriented screens, views that require fast iteration, easy updates, and primarily focus on presenting

information rather than handling complex client-side logic. This approach allowed teams to move faster and gave product owners the ability to adjust screens

without waiting for a full mobile release cycle.

Over time, however, product expectations shifted. Many screens that used to be “content-only” started requiring richer interactions, dynamic state handling, and

more advanced UI behavior. This naturally pushed MBox into areas it wasn’t originally optimized for, increasing both implementation complexity and maintenance

cost.

One limitation became increasingly difficult to ignore: the absence of client-side JavaScript support. Without a scripting layer, implementing even moderate

interactivity often required custom solutions, additional platform work, or growing the MBox component surface area, which made the system harder to evolve.

At the same time, engineers working on MBox-driven UI increasingly expected a more modern development experience. Many frontend engineers naturally gravitate

towards a React-based workflow, not only because it’s widely adopted, but also because it comes with mature patterns, tooling, and a large ecosystem.

Another recurring question was cross-platform reuse: if many of these content screens are conceptually similar to web views, why can’t we share more with the

web stack? And if we do, can we avoid the classic compromise of embedding a WebView, with its drawbacks in performance, UX consistency, and long-term

maintainability?

Problem #

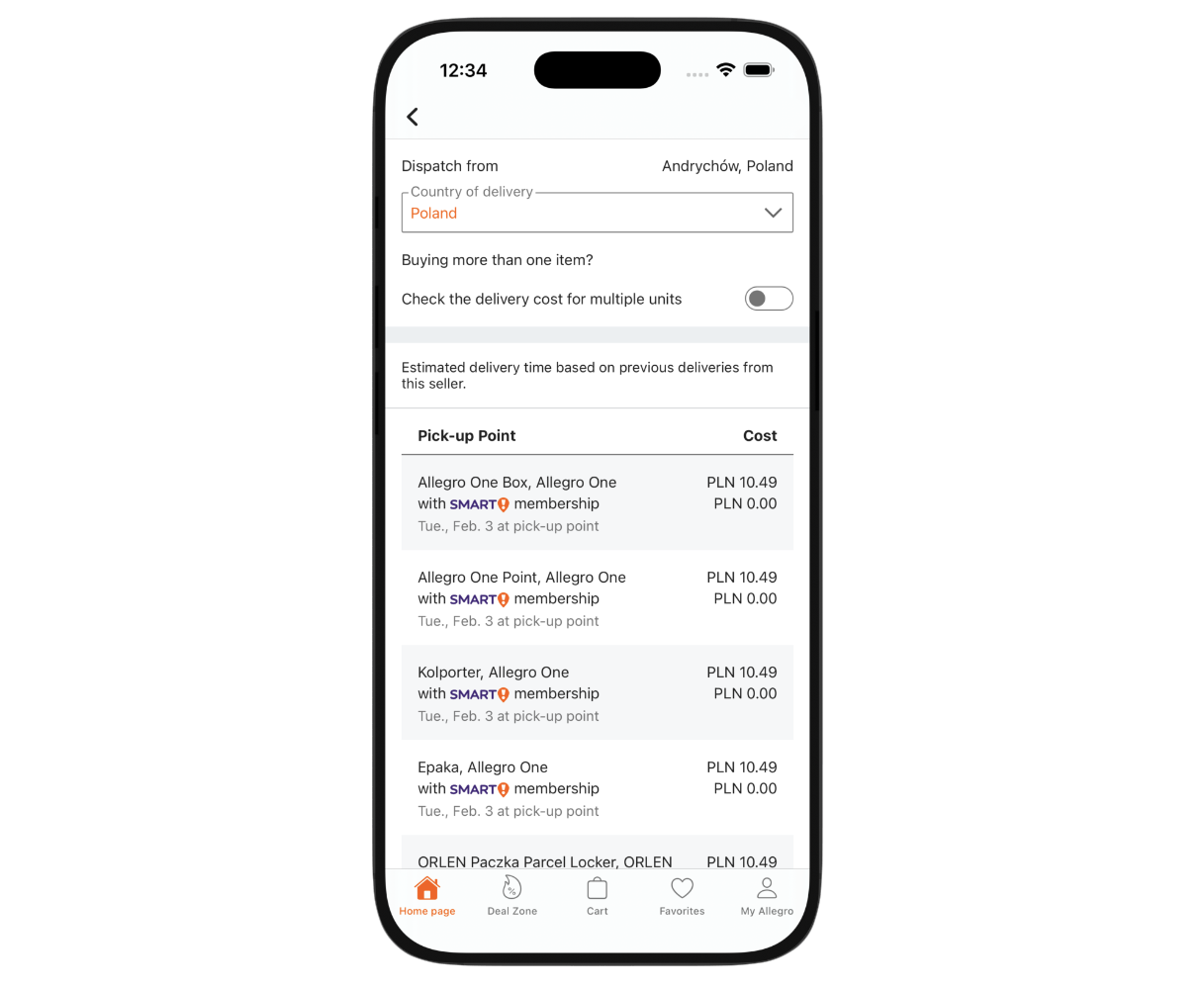

We wanted to battle-test Lynx technology by reimplementing one of Allegro’s mobile screens and setting up A/B testing to compare the Lynx-based solution against

our current WebView implementation.

The image above shows the reimplemented screen. We chose a screen that wasn’t overly complex but still included specific requirements we wanted to test Lynx

against.

To ensure compatibility with the Allegro mobile app, we had to meet several additional requirements:

- Full analytics support,

- Theming (light and dark mode),

- Reuse of the current design system,

- Accessibility support,

- Font and element scaling,

- Support for custom native elements,

- Communication with the mobile host application,

- Translations.

Implementation #

Once the project requirements were finalized, we moved into the implementation phase.

Architecture #

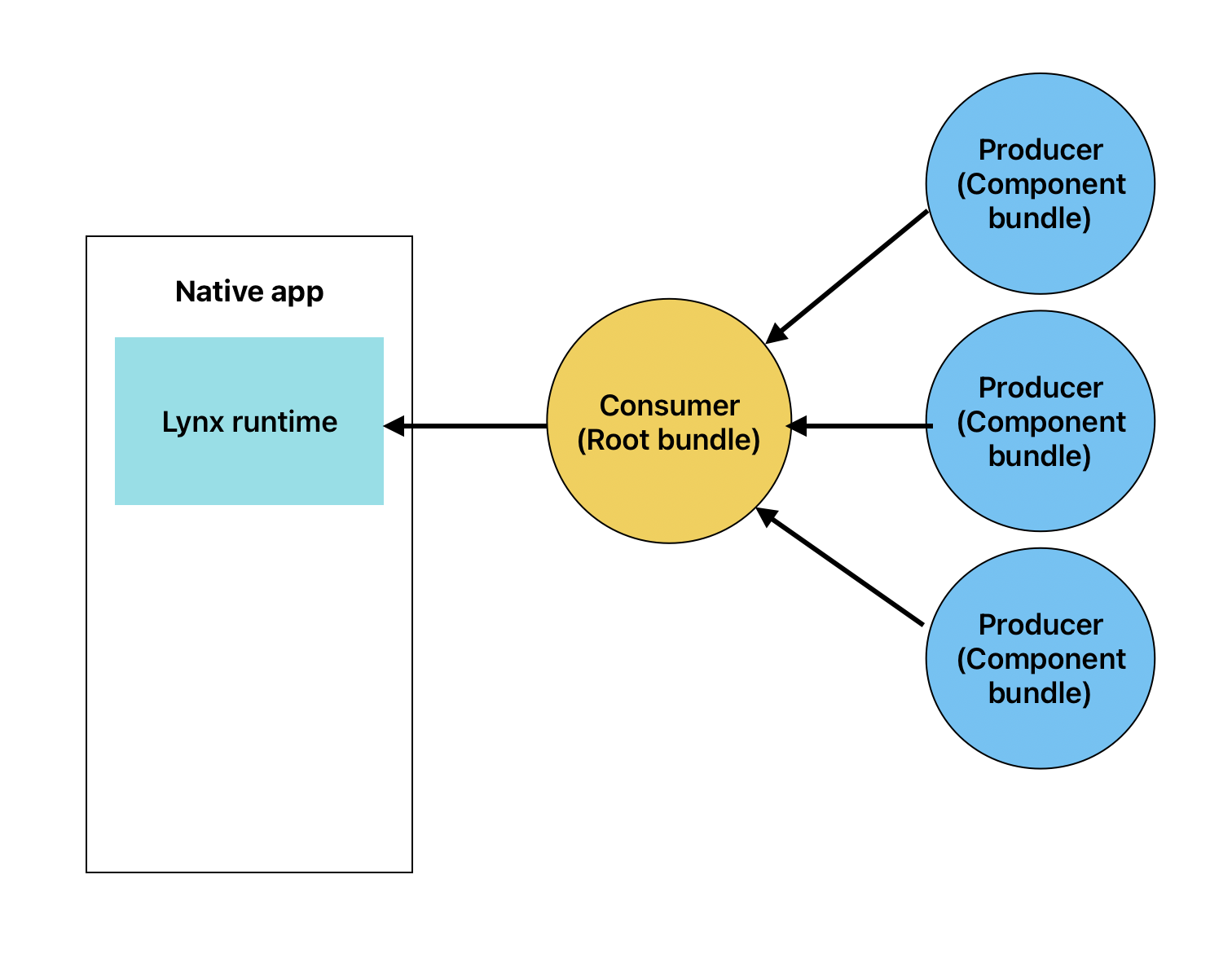

The key objective was to ensure that this new rendering approach remained consistent with Allegro’s current architectural standards: a micro-frontend-based

architecture. We wanted components to be implemented and built independently,

with the resulting code fragments (bundles) fetched dynamically.

This approach is supported by Lynx via a feature called Code splitting. Adopting it was a natural choice to

maintain architectural consistency across the organization.

Using this approach, the project was divided into the following parts:

- Lynx runtime: The Lynx engine embedded within the native application.

- Consumer: (referred to internally as the Root Bundle).

- Producer: (the Component Bundle).

Root bundle #

The Root Bundle (consumer) was the primary component in our architecture. Within the application, it served several purposes:

- Fetching and rendering component bundles.

- Communicating with the native application: fetching data and utilizing native modules.

- Managing the application theme (light and dark).

- Providing shared modules, such as analytics.

These goals stemmed from our desire to prevent “Lynx leakage” into the business components. We wanted the components to be as unaware of Lynx’s underlying

presence as possible. Additionally, we aimed to minimize bundle sizes by extracting reusable modules, such as analytics and CSS variables for theming into the

Root Bundle.

Component bundle #

This is the basic building block of any given screen. Specific components contain the business logic; they are subsequently fetched and rendered within the

context of the Root Bundle.

Native implementation #

In addition to the JS layer, the project required native-side implementation. Despite the relatively simple view used in the experiment, we lacked native

controls like Switch and Select. Furthermore, we needed to implement custom native modules and expose them to the JS layer.

Custom native elements #

We used Lynx version 3.4 for this implementation. Most of the tested screen could be built using the standard controls provided by Lynx, such as view, text, and image. However, because Switch and Select were missing, we had to implement them ourselves. Lynx allows the creation of Custom Native Elements, which we integrated using the provided API.

Native communication #

Communication between the JS code (Lynx) and the native application was handled in two ways: by exposing native data to the JS layer and by providing a native

API for the JS layer to call. To avoid leaking Lynx-specific code into business components, only the Root Bundle had direct access to native modules.

Data shared by the native layer was accessed in JS using the useInitData hook. This data was previously registered using registerDataProcessors. To pass data from the Root Bundle down to individual components, we used Context, a standard React mechanism fully supported by Lynx.

The specific data passed from the native layer to the JS code included:

- theme: The user’s preferred color scheme.

- lang: The currently selected language.

- boxes: The list of components to be rendered by the Root Bundle.

- analyticsParams: The analytical context defined for the entire page.

Communication in the other direction (from JS to native) was facilitated by Native Modules.

The modules we exposed from the native layer included:

- storage: Local storage management.

- link: Navigation handling.

- http client: For sending HTTP requests.

- logger: For console logging.

- analytics endpoint: For dispatching analytical events.

Lower-level components containing business logic required access to these native modules. Since we didn’t want to expose them directly for the reasons mentioned above, we made them available using the registerModule API. The Root Bundle registered the native modules, which were then accessed within components via the getJSModule function. This solution had one limitation: getJSModule is only accessible on the Background Thread. In our case, this wasn’t an issue as the native modules were only needed for background logic. We also considered placing them in a global variable accessible across all bundles as an alternative.

Styling #

Styling was a critical topic. We wanted our styling workflow to be as close to web standards as possible. At the same time, Allegro has a very well-defined

design system, and we wanted to reuse as much of our existing CSS class infrastructure as possible within Lynx.

The Lynx approach to styling offered several advantages, but also presented some challenges:

✅ Pros

- CSS Class Reusability: Most CSS classes developed for our web platform can be reused in Lynx, promoting consistency across platforms.

- Shared CSS Variables: Variables used for theming (e.g., colors) can be shared across bundles, creating a single source of truth for the theme.

- DOM-like Operations: While Lynx’s DOM operations are more limited than web standards, they still allow for retrieving element dimensions (width/height)

and performing basic manipulations. - Native Animation Support: Lynx provides a dedicated, high-performance API for handling animations.

- Layout Standards: It supports common patterns like Flexbox, Grid, and relative positioning.

❌ Cons

- Limited CSS Variable Nesting: Support for CSS variables is currently restricted to single-nested variables.

- Property Discrepancies: Some standard CSS properties are missing and others have different values.

- No Class Sharing Between Bundles: Lynx does not currently support sharing CSS classes between the Root Bundle and component bundles. This results in

duplicated CSS in each bundle, which can lead to “bundle bloat”. We are currently investigating workarounds for this issue. - Different Inlining Logic: Making elements display inline is handled differently:

- Web: Use

display: inline. - Lynx: Wrap elements within a

- Web: Use

Theming #

The Allegro native app supports two color themes: light and dark. We implemented this using the recommended Lynx approach:

Theming. Given our architecture, we wanted the component bundles to remain “theme-agnostic”. Consequently,

all theme management logic resides in the Root Bundle. Information about the current theme is retrieved using:

const { theme } = useInitData();

Then, based on the theme value, we inject a CSS class containing the corresponding theme variables:

export const Theme = ({

children,

theme = 'light',

}: {

children: ReactNode;

theme?: ThemeType;

}): ReactElement => {

const isDarkMode = theme === 'dark';

const themes = [common, theme === 'dark' ? dark : light].join(' ');

return (

Root className={themes}>

{children}

Root>

);

};

Analytics #

Both the native and web platforms at Allegro have established approaches to analytics. For this project, we needed to implement:

pageView,boxView,- custom events triggered by user interactions.

The pageView event is sent when a user enters a page. Each component (component bundle) then sends the boxView event once it becomes visible. Finally,

interaction events are triggered by user actions.

Our first step was to expose a native module for sending these analytical requests.

The pageView event was defined and dispatched from the Root Bundle. This was the logical place for it, as there is exactly one Root Bundle per screen. We used the useEffect hook, which Lynx supports.

The next event was boxView. Since this needs to fire when a user views a specific box, it was defined at the individual component level. Lynx provides binduiappear and binduidisappear callbacks, which we used to implement the boxView logic. This allowed us to accurately track which boxes were actually seen by the user.

Custom events were managed at the Root Bundle level because it had access to the analytical context provided by the native app. These were then passed to the component bundles via the registerModule and getJSModule APIs.

Accessibility #

Lynx employs an attribute-based accessibility model similar to web standards. Our implementation confirmed that core functionalities such as nesting, tagging,

and disabling accessibility elements are robust and reliable. This allowed us to successfully implement most of the accessibility patterns we required. However,

we did encounter several limitations and required workarounds that could prove problematic in the future.

We faced several challenges with Lynx accessibility:

- Outdated Documentation: The official documentation is sometimes inaccurate, as many properties have changed or been removed. We often had to analyze the

source code directly to find the correct usage. - Android Performance Trade-offs: To make elements readable by TalkBack on Android, the

flattenoptimization flag must be disabled for each accessible

component. This could potentially impact performance on very complex screens. - Single Accessibility Trait: The Lynx API only supports a single value for an element’s accessibility “role” (trait). Assigning multiple states (e.g.,

accessibility-traits="button,selected") requires custom type overrides and extra effort. - iOS Select Element Issues: A limitation in the implementation prevents native iOS select elements from being fully grouped for VoiceOver. This causes

VoiceOver to announce them as a series of disconnected items rather than a single interactive control.

Font scaling #

Font scaling is a vital accessibility feature. In Lynx, this is toggled by adding the enable-font-scaling property to a text element. However, we noticed

platform-specific scaling bugs:

- Android: There is a bug with nested text elements where the property should only be present on the root text element. Applying it to nested text elements

results in “double scaling.” - iOS: Conversely, iOS requires the property to be present on all text elements, regardless of nesting, to scale correctly.

We created an abstraction to handle these differences, but it remains a manual task for developers to disable scaling (since it’s enabled by default) on nested

elements for Android, which increases the risk of visual bugs.

Conclusion #

As a final result, we successfully implemented the screen in Lynx, embedded it into the native application, and launched our A/B tests. We compared a

traditional WebView-based implementation with a Lynx-powered view, measuring both business and technical metrics. From a business perspective, Lynx showed a

slight improvement in key KPIs, confirming its potential to positively impact user experience. Seeing the same code render natively on both platforms was also a

good validation of the framework’s core promise.

On the technical side, core stability metrics such as CFU remained at an acceptable level. However, during the “battle-testing” phase, we observed JavaScript

engine crashes, some of which started occurring in production environments and required immediate hotfixes. While the transition was technically successful,

these incidents exposed strategic and operational risks that are difficult to ignore at our scale.

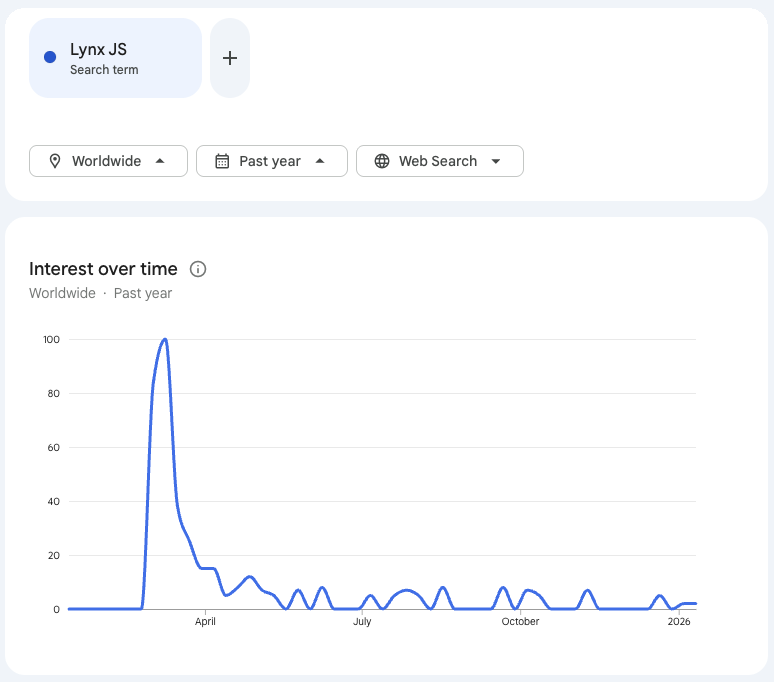

To sum up, while Lynx shows significant potential in the mobile cross-platform framework market, we have decided not to move forward with it at Allegro for now.

Here is a deeper look into the risks and limitations that led to this decision:

The Web Rendering & SEO Gap #

One of the primary drivers for exploring Lynx was the potential for “Write Once, Run Everywhere” sharing code across iOS, Android, and Web. However, for an

e-commerce platform like Allegro, the Web is not just an app runtime; it is our primary acquisition channel. We discovered that Lynx currently lacks support for

Server-Side Rendering (SSR). For internal tools, this might be acceptable, but for our public-facing product pages, SSR is critical for SEO and First Contentful

Paint metrics. Without it, we cannot render Lynx content to the web in a way that search engines can efficiently index, effectively nullifying the “web” part of

the cross-platform promise for our use case.

Friction with Modern Native Stacks #

Mobile development is rapidly shifting toward declarative UI frameworks like SwiftUI and Jetpack Compose. Our internal teams are aggressively adopting these

modern standards. Lynx, however, relies on a more traditional stack under the hood: Objective-C, UIKit, and Android Views. During our implementation, we found

that integrating custom components (like our Switch and Select) with modern SwiftUI or Compose layouts was harder than anticipated. Additionally, the build

system required older versions of Gradle, introducing friction into our CI/CD pipelines and conflicting with our efforts to modernize our codebase.

Maintenance & Competency Risks #

Adopting a core technology implies being able to fix it when it breaks. A significant portion of Lynx’s core engine is written in C++. While this ensures

performance, it sits outside the primary competencies of our mobile engineers (who specialize in Swift, Kotlin, and TypeScript). Contributing fixes or debugging

deep runtime errors would be difficult for our team. Furthermore, the open-source community around Lynx is currently limited, with the majority of contributions

coming from the original authors. This creates a “vendor lock-in” risk where we might be unable to resolve critical engine bugs independently.

Maturity #

Finally, while the core features are solid, the “last mile” of development revealed rough edges typical of younger frameworks.

Accessibility vs. Performance Trade-offs: Beyond the font scaling bugs, we faced a critical conflict on Android. To make components readable by TalkBack, we

were forced to disable the flatten rendering optimization for those views. This presented an unacceptable choice: degrade performance to gain accessibility, or

sacrifice inclusivity for speed.

While Lynx mimics web standards, it deviates in subtle, frustrating ways. Basic tasks required non-standard approaches, such as physically restructuring the DOM

to achieve inline styling (where display: inline is replaced by wrapping elements in

discrepancies break the “web developer mental model” and complicate code sharing.

Documentation Gaps: We frequently found the official documentation to be outdated or inconsistent with the current API. Our team often had to analyze the C++

source code directly to understand property behaviors or uncover hidden limitations, a workflow that slows down onboarding and increases maintenance overhead.

Missing UI Primitives: Despite being a UI framework, Lynx lacked standard native controls like Switch or Select out of the box. We had to implement these as

Custom Native Elements ourselves.

The Verdict #

Lynx is a powerful technology with a unique value proposition, particularly for super-apps or environments where SEO is not a constraint. However, the

combination of SEO limitations, a legacy-reliant native stack, and the high barrier to entry for core contributions makes it a risky choice for Allegro at this

moment.

Consequently, Lynx remains “on hold” on our Allegro Tech Radar. We will continue to watch its evolution, particularly regarding

SSR support and interoperability with SwiftUI and Compose and may revisit it as the ecosystem matures.

Discussion