Dhaka, Bangladesh – As Rubel Chaklader drove his autorickshaw through the busy Dhaka traffic in late January, he sounded more resigned than angry.

The 50-year-old said that Bangladeshis had squandered what he saw as a rare opening after an uprising in August 2024 toppled longtime leader Sheikh Hasina, ending her 15-year rule marked by allegations of authoritarianism, crackdown on opponents and widespread rights abuses.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

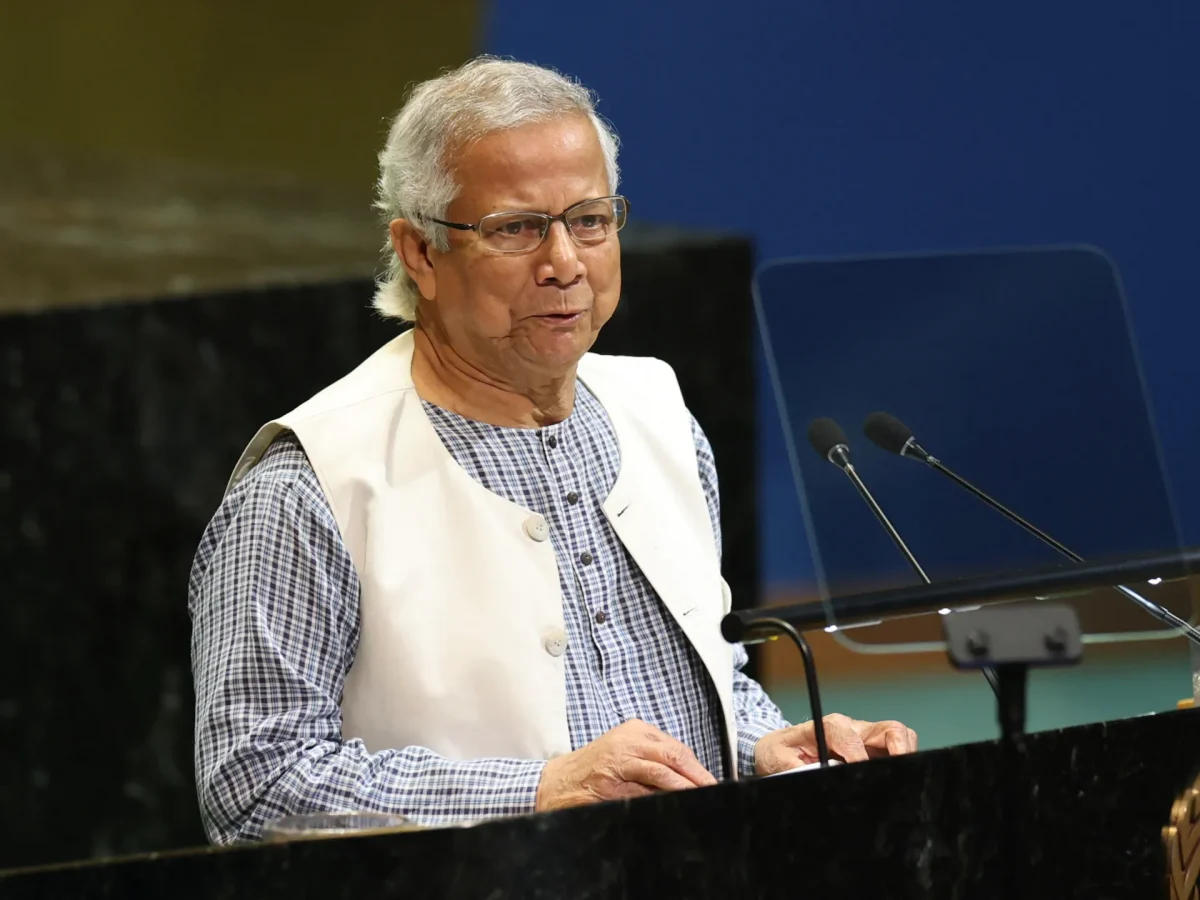

Three days after the student-led protests forced Hasina to resign, Muhammad Yunus, Bangladesh’s only Nobel laureate, took over as the country’s interim leader, tasked with stabilising a fractured country after one of its bloodiest upheavals that killed more than 1,400 people.

Yunus, now 85, framed his mandate narrowly but ambitiously: restore a credible electoral process, and build consensus around reforms aimed at preventing a return to authoritarian rule by balancing power among different state institutions.

And that’s where Chaklader thinks the various vested interest groups – officials inside the administration and polarised political parties – failed to support Yunus enough to deliver more substantial changes during his 18 months of rule as an interim leader.

“We missed the opportunity,” Chaklader told Al Jazeera. “We didn’t let Dr Yunus work properly. Who didn’t come to the streets with unreasonable demands from him? This country will never be good. People gave their lives in July for nothing.”

His weary assessment came as Yunus prepares to leave office after presiding over arguably the country’s first free and fair elections in more than a decade, closing one of the most unusual political transitions in the country’s history.

As Bangladesh heads towards the February 12 polls, spirited debates over Yunus’s legacy are already dividing people who once placed their hopes on him.

The key question at the heart of those debates: was Yunus the steady hand who kept a fragile state from breaking, or a leader who fell short on delivering the structural change demanded by the movement that powered the 2024 uprising?

‘Acceptable to everyone’

For the student leaders who spearheaded the uprising, Yunus’s global stature as an eminent economist as well as his domestic reputation as a civil society leader mattered, particularly as Bangladesh, a garment exports powerhouse, sought to reassure the world of avoiding an economic freefall.

“At that moment, we needed someone acceptable to everyone,” said Nahid Islam, a prominent student leader who now heads the National Citizen Party (NCP), a new political platform formed by former student protest leaders. The NCP is now in alliance with Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party, the Jamaat-e-Islami, in next week’s election.

“When we discussed alternatives, we didn’t find anyone other than Yunus,” he added.

Asif Mahmud Shojib Bhuiyan, another student leader who contacted Yunus days before Hasina’s fall, said their calculation was similar: addressing institutional collapse and global uncertainty required someone with moral authority.

Bhuiyan said Yunus’s appointment was not unanimously welcomed within state institutions, and cited reservations within the military that he claimed were voiced during discussions among student leaders and officials at the time. Al Jazeera cannot independently verify this claim. The military has not publicly detailed its internal deliberations around Yunus’s appointment, and General Waker-Uz-Zaman, the army chief appointed by Hasina, remained in his post under the interim government.

Yunus is also reported to have initially hesitated, insisting he was “not a political person”. But as protests escalated and deaths mounted, he stepped in, in “a moment of obligation”, as political scientist Ali Riaz puts it.

“He felt a commitment to step forward,” said Riaz, who was handpicked by Yunus to head a committee on constitutional reforms – a key demand of the 2024 uprising.

But 18 months later, a sense of disappointment – and missed opportunity – hangs over even those who backed Yunus.

“We wanted a national unity government,” Bhuiyan added. “That wasn’t possible. Still, we expected a rigorous overhaul of the state.”

Push for justice

To be sure, Yunus presided over one of the most ambitious and contested reform drives attempted by any interim government in Bangladesh’s history. In the absence of an elected parliament, his administration relied on experts to diagnose the failures of governance, document the abuses of power and propose structural fixes before holding a general election.

Supporters saw it as long overdue truth-telling. Critics saw an unelected government trying to do too much, too quickly.

Yunus’s administration set up multiple reform and inquiry commissions covering elections, constitution, judiciary, police, as well as the various rights abuses carried out under Hasina’s administration, including arrests of critics, extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances.

The judiciary, which during Hasina’s rule was also accused of systemic repression, assumed a more independent role and ordered the trial of several politicians, army generals, police officers and other security officials who were implicated in past abuses. Late last year, Hasina was sentenced to death in absentia for crimes against humanity and convicted in other cases, while several other Hasina-linked officials also faced the wrath of the law.

Among Yunus’s most sensitive initiatives was confronting the issue of enforced disappearances and secret detentions under Hasina’s watch between 2009 and 2024.

The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances, which he formed, documented 1,913 complaints, verified 1,569 cases, and identified 287 victims as either missing or dead, with most of those cases to security agencies, including the police, the Rapid Action Battalion, a notorious paramilitary sanctioned by the United States and the military intelligence.

Mubashar Hasan, an adjunct fellow at Western Sydney University, who was himself abducted in Dhaka in November 2017 and returned home 44 days later after being left blindfolded on a highway, called the commission Yunus’s “most consequential intervention”.

“It showed that crimes under Sheikh Hasina were systematic,” Hasan said.

He credited Yunus with acknowledging Aynaghor or “house of mirrors” – as Hasina-era clandestine detention sites were called – and visiting suspected locations, despite resistance within the security establishment.

But Hasan also felt the commission could have a broader mandate, comparing it with a truth and reconciliation commission in post-dictatorship Argentina. “It [Bangladesh commission] was a success,” he said, “but it could have been a bigger one.”

The interim government under Yunus also engaged with the United Nations Human Rights Office, which confirmed that Bangladeshi security forces used excessive force during the July 2024 uprising, lending international weight to claims of serious violations.

Political analyst Dilara Choudhury thinks bureaucratic reforms were another area where expectations did not match the outcome during Yunus’s rule.

“There was an expectation that Yunus would confront an entrenched bureaucracy that routinely exercises power over citizens,” she told Al Jazeera. “But he failed to do so, constrained by structural resistance and the limits of an unelected mandate.”

Referendum on reforms

Yunus is using the February 12 vote to attempt something unprecedented in Bangladesh’s history: forging political consensus around key recommendations and putting them directly to voters through a nationwide referendum alongside the general election.

Yunus’s supporters argue that if the next government is to dismantle systems that enabled repression during Hasina’s abuse of power – from politicised courtrooms to unaccountable security forces – then the reforms require public consent.

If voters approve the charter, the next parliament will decide whether those reforms are to be implemented. If not, the reform initiatives may be shelved.

For analysts, that uncertainty defines Yunus’s legacy.

“He provided leadership at a moment when Bangladesh could have fallen apart,” said Hasan, the Sydney-based political analyst. “History will judge what survives after he leaves.”

Choudhury offered a different perspective. “Whether the initiatives he took ultimately succeed or fail is not the only measure,” she said. “He will remain a permanent figure in the nation’s history.”

Bangladesh’s political parties, however, remain divided on Yunus’s legacy as they seek to form an elected government later this month.

The frontrunner Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which had been demanding swift elections since Hasina’s fall, did not approve of an unelected government in command. On the other hand, the NCP and its ally, the Jamaat-e-Islami, favoured deeper reforms before an election was held.

BNP leader Salahuddin Ahmed acknowledged Yunus’s role in stabilising the country, but questioned how far an unelected government should have gone.

“There was a tendency to try to do everything within this short time,” Salahuddin told Al Jazeera. “Some of these issues could have been addressed later through parliament once an elected government was in place.”

He said law and order had been “largely under control, though not to expectations”, while economic stability remained fragile, with foreign investments largely stalled during the interim period.

Economists say that while macro indicators stabilised somewhat under Yunus, household-level distress persisted – with unemployment, stagnant wages and sluggish investment keeping private sector confidence low and limiting the government’s capacity to generate growth and jobs.

Still, the BNP leader described Yunus’s decision to hold elections on February 12 as a “major achievement”, adding: “How much of what [reform agenda] he has initiated will be accepted or implemented by the next parliament remains an open question.”

The Jamaat-e-Islami, which supported Yunus’s appointment after Hasina’s fall, struck a similar note.

“He started the reform process and made significant progress,” Jamaat leader Abdul Halim said. “But reforms need time. This government’s achievements should be seen as a collective effort by all political forces.”

‘A country of the blind’

Among the student leaders who propped up Yunus, assessments blend respect with a degree of disappointment.

Islam, who also served as the acting head of the information ministry in the Yunus cabinet before forming the NCP a year ago, said Yunus’s intent was clear but political realities were unforgiving.

“He tried to create unity,” Islam said. “But his government was weak in political negotiations.”

Bhuiya agreed, saying Yunus succeeded internationally but struggled at home. “We needed stronger positions,” he told Al Jazeera.

For Sanjida Khan Deepti, however, Yunus will be remembered more for his government’s push for justice for the victims of the 2024 uprising. Deepti’s 17-year-old son Anas was killed by the police at the peak of the uprising in early August 2024.

Last month, a court sentenced former Dhaka police chief Habibur Rahman and others to death, while several officers received prison terms for their crackdown on the protesters.

“We gave our children’s lives in exchange for justice,” Deepti told Al Jazeera.

She insisted that Yunus should be remembered positively. “In a country of the blind, a mirror has no value,” she said. “How could one person finish so many tasks in such a short time?”

Back in the crawling traffic of Dhaka, Chaklader slowed his autorickshaw near the Bashundhara neighbourhood and turned around to share a family secret: his wife and daughter remain staunch supporters of Hasina’s banned Awami League party and he has failed in persuading them otherwise.

And that, he explains, is why he has little hope for the February 12 election.

“I will still vote,” he told Al Jazeera. “Not because I expect change, but because there is nothing else left to do. I don’t believe the election would alter my life – or the country – in any meaningful way.”