Did you know…?

LWN.net is a subscriber-supported publication; we rely on subscribers

to keep the entire operation going. Please help out by buying a subscription and keeping LWN on the

net.

In traditional build tools like Make, targets and dependencies are always

files. Imagine if you could specify an entire tree (directory) as a

dependency: You could exhaustively specify a “build root” filesystem containing

the toolchain used for building some target as a dependency of that target.

Similarly, a rule that creates that build root would have the tree as its

target.

Using Merkle

trees as first-class citizens in a build system gives great

flexibility and many optimization opportunities. In this article I’ll

explore this idea using OSTree,

Ninja, and Python.

OSTree

OSTree is like Git, but for

storing entire filesystem images such as a complete Linux system. OSTree

stores more metadata about its files than Git does: ownership, complete

permissions (Git only remembers whether or not a file is executable), and

extended

attributes (“xattrs”). Like Git, it doesn’t store

timestamps. OSTree is used by Flatpak,

rpm-ostree from Project Atomic/CoreOS, and GNOME

Continuous, which is

where OSTree was born.

My company has been using

OSTree to build and roll-out software updates to Linux-based devices

for the last four years. OSTree provides deployment tools for distributing

images to different machines, deploying or rolling back an image

atomically, managing changes to /etc, and so on, but in this article

I’ll focus on using OSTree for its data model.

Like Git, OSTree stores files in a “Content

Addressable Store”, which means that you can retrieve the contents of

a file if you know the checksum of those contents. OSTree uses SHA-256, but I will use

“SHA” and “checksum” interchangeably. This store or

“repository” is a directory in the filesystem (for example

“ostree/“) where each file tracked by OSTree (a

“blob” in Git terminology) is stored under

ostree/objects/ as a file whose filename is the SHA of its

contents. This is something of a simplification because file ownership, permissions, and xattrs

are also reflected in the checksum.

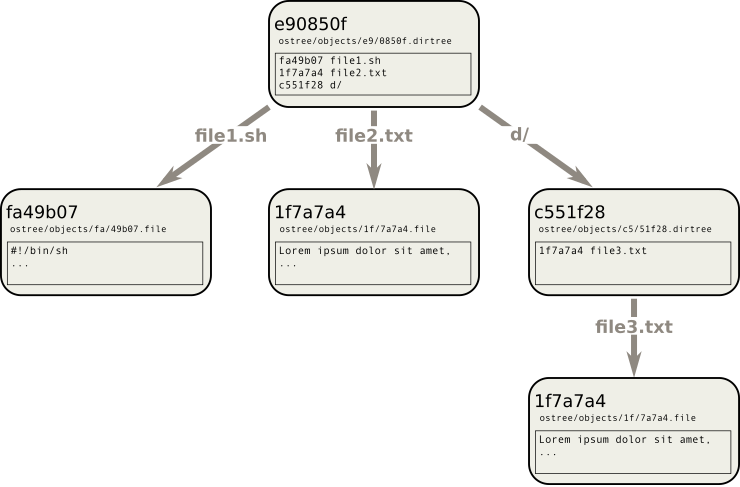

A “tree” (directory) is stored as a file that contains a list of files and

sub-trees, and their SHAs. The filename of this file, just like for blobs, is

the SHA of its contents. This way the entire tree, including its sub-trees and

their sub-trees, and the contents of each of the files within, can be uniquely

identified by a single SHA. This data structure is called a Merkle tree.

You can have different versions of a tree, like Git commits or Git

branches, or completely separate trees, but any common files are stored

only once in the OSTree repository (in the figure above, file2.txt

and d/file3.txt are identical so they are stored only once in

ostree/objects/). Like Git, OSTree has “commit” and

“checkout” operations.

OSTree “refs” (short for

“references”), similar to Git refs, are how OSTree implements

branches and tags. A ref is a metadata file in the OSTree repository: Its

filename is whatever you want it to be, such as the branch or tag name, and its

content is a single SHA pointing at a tree. The connection to the tree is

indirect as it is really the

SHA of a “commit” which in turn points at a tree, but in this

article I’ll ignore commits as they aren’t directly relevant.

OSTree + Ninja

Ninja is a build system similar

to Make. I covered Ninja for LWN three years ago. Unlike Make,

Ninja doesn’t support wildcards or loops, so you’re supposed to write a

“configure” script to generate a Ninja file that specifies each

build target explicitly. At my company, the internal build system is a

3,000-line Python file, plus several dozen YAML files with packaging instructions for

various components; when run, this Python script generates a 90,000-line

Ninja file.

In Ninja (like Make) build targets and inputs are files. OSTree refs are

also files. The build system, then, creates a different ref for each build

step, and the ref itself is the target (output) of that build rule. For

example, the target of a generated Ninja rule might be the file

“build/ostree/refs/heads/xyz“, where “build/ostree” is

the OSTree repository in the “build” output directory, and

“xyz” is the ref name.

Here’s a concrete example from the build system, where it builds a rootfs for

the Linux devices:

rootfs = ostree_combine([

l4t_kernel(),

bionic_userspace(),

package("a"),

package("b"),

container("c"),

])

phony("rootfs", rootfs)

default(rootfs, ...)

Each of l4t_kernel(), bionic_userspace(),

package(), and container() is a Python function that creates

an OSTree tree (perhaps by downloading and unpacking a tarball, or by

running an upstream makefile, the details don’t matter right now), then

creates an OSTree ref pointing at this tree, and returns the ref (which is

a Python string generated internally, perhaps

“build/ostree/refs/heads/package/a“).

ostree_combine() is a Python function that takes any number of

OSTree refs, each of which points at a tree; it combines them

together into a single tree, creates another ref pointing at this tree, and

returns the ref (this time it might be called

“build/ostree/refs/heads/ostree_combine/c85e333f577b“).

But I lie — these functions don’t do any of this at all. What they

do do, is write a Ninja rule, that when invoked via

ninja, will carry out those steps.

When you run ninja in an incremental build, if any of the input refs changes

— remember, a ref contains a SHA pointing at a tree, so if any file in the

tree changes then the ref’s content will change — then Ninja will know that

the rootfs target is out of date and the ostree_combine rule needs to be

re-run.

Crucially, you never need to write out any of these ref filenames explicitly in

the build script; you pass them around like any normal Python variable, and

other functions can take them and record them as dependencies in their own

Ninja rules.

In the example above we also create a Ninja phony

rule to create a top-level target name that is convenient to type at the

ninja command line, and we add it to Ninja’s list of default

targets.

Benefits

The ability to specify entire trees as build dependencies or targets

means that the same mechanism can be used for specifying

coarse-grained dependencies (such as third-party packages that are being

integrated into the rootfs) as for fine-grained dependencies (individual

files). One obvious benefit is that toolchains and

build environments can be managed explicitly: The rule to compile something can

take a “build root” rootfs as one of its dependencies, and chroot

into it to run the compilation command (some literature calls this “hermetic

builds“). This build rootfs can itself be created by other

rules.

Less obvious, but possibly the best thing about this approach, is the

ability to pass intermediate build outputs around as

variables. We saw an example in the Python snippet earlier, where

package("a") returns a target name that we passed into

another rule, ostree_combine(). This means you don’t have to come

up with a name for every single intermediate artifact; you can generate

them automatically. The composability leads to concise and readable

build scripts: the example above is not at all contrived, it is very

similar to the production build script. By making this easy to express,

it is easier to exploit opportunities to cache or parallelize steps in

the build.

To provide a (somewhat contrived) example: Generating the ldconfig cache only

depends on the contents of a few directories like /lib and /usr/lib;

similarly, the mandb cache only depends on the contents of

/usr/share/man.

Traditionally, these operations are run in series. But a build system

that can define a dependency that is a subtree of a previous

target, could specify separate rules for these operations, run them in

parallel, and then merge the results back into a final rootfs tree. In

this example, even if the rootfs SHA changes, it’s possible that the

/usr/share/man subtree hasn’t changed, so there’s no need to

re-run mandb. In the diagram above, red arrows operate on data

(file contents); green arrows operate on OSTree metadata.

[Update (added paragraph)]

You can imagine there are applications of this to “cloud” build systems

that farm out the execution of individual build steps to remote build

servers: To run this mandb rule, a remote server doesn’t need to

download the entire rootfs, only /usr/share/man. Merging the output

from this build step back into the rootfs can be done by operating solely on

Merkle tree metadata.

OSTree’s tooling also gives a few compelling benefits that really need

to be pointed out, but you can get them by exporting (committing) the final

build artifacts to an OSTree repository (you don’t need the close OSTree

integration, throughout the intermediate build steps, that I have been

describing):

-

Visibility of changes: My company’s continuous integration (CI)

system runs ostree diff on each pull request, so that the developers can see

exactly which files changed in the output rootfs. This is a wonderful tool

for gaining confidence in the correctness of the incremental

builds. -

Fast incremental deployment: OSTree provides tools

for deploying a tree to a remote device. This is used to deploy changes to

devices in the field (“over the air” software updates) but this

same, production software update process is fast enough for interactive

development (an incremental build + deploy + reboot in under a

minute).

Implementation details

Our Python script has various functions for getting files, tarballs, Git

snapshots, and apt packages into OSTree. A tree can consist of as little as

a single file, and refs are cheap.

There are also various functions to manipulate trees, such as

ostree_combine() in the example above, but also

ostree_ln(), ostree_mkdir(), and

ostree_mv(). These are fast because they operate directly on

OSTree metadata; they don’t need to do ostree checkout to

manipulate the trees. Note that a ref can point to any tree, it doesn’t

have to be rooted at the “/” of your final image.

To run a command, such as a compilation, there is ostree_mod(),

which modifies a tree by running a given command. It will check out the

specified tree, optionally chroot into it, run the specified command, and

create a new tree from the output. For example:

ostree_mod(

input_tree=ostree_combine([build_root, src]),

command="make -C /src install DESTDIR=/dest",

chroot=True,

capture_output_subdir="/dest")

This uses fakeroot

and bubblewrap to

sandbox the command so that it can’t access anything outside of the input

tree. Bubblewrap is a tool born from Red Hat’s

Project Atomic, and used by Flatpak among others, that allows

unprivileged users to create secure sandboxes. Here bubblewrap is not used for security,

but as a convenient way of ensuring correct, “hermetic”

builds. Our version of fakeroot is heavily

patched so that the build command sees the file permissions that are

stored by OSTree; this allows us to run the build as an unprivileged user

but still modify root-owned files.

OSTree’s “bare” repository format is used, which means that the

checkout operation only needs to create hard-links to the relevant files

inside the repository; this needs to be fast because every build rule

that calls ostree_mod() involves an ostree checkout and an

ostree commit. OverlayFS is used to

ensure that the OSTree repository is not modified by accident via those

hard-links. This

patch for bubblewrap is needed to support OverlayFS; the patch probably isn’t

upstreamable because it requires additional capabilities, which is at odds

with the bubblewrap project’s security goals. There are also several OSTree

patches, some of which are merged and some not (yet).

apt2ostree

apt2ostree is a

tool that has been extracted from our build system. It builds a

Debian/Ubuntu rootfs from a list of .deb packages — much like

debootstrap or multistrap. Unlike those tools, the output is an OSTree tree

rather than a normal directory. It is faster, parallelized, and

incremental. It also records package versions in a “lockfile” for

reproducible builds.

From a list of .deb package names, apt2ostree downloads and unpacks each

package into its own OSTree tree, then it combines these into a single tree

(so far this is equivalent to debootstrap’s “stage 1”). It then

checks out the tree, runs dpkg --configure -a within a

chroot (“stage 2”), and commits the result to OSTree.

From a list of packages, apt2ostree performs dependency resolution (via

aptly) and generates a

“lockfile” that contains the complete list of all packages, their

versions, and their SHAs. This lockfile can be committed to Git. Builds from

the lockfile are functionally reproducible.

“Stage 1” of apt2ostree is fast for several reasons. It only

downloads and extracts any given package once; if it is used in multiple

images it doesn’t need to be extracted again. This saves disk space too,

because the contents of the packages are committed to OSTree so they will share

disk space with the built images. Downloading and extracting is

done in a separate Ninja rule per package; this allows parallelism (it can be downloading

one package at the same time as compiling a second image, or performing other

build tasks within the larger build system, all thanks to Ninja) and

incremental builds (there is no need to repeat work if the package version hasn’t

changed). Combining the contents of the packages is fast because it only

touches OSTree metadata.

apt2ostree only has a single user as far as I know (my company’s build

system). See the README file in the apt2ostree repository

on GitHub for more information. I don’t necessarily expect anyone to use

it, but it serves as a good self-contained example of the techniques

described in this article.

Conclusions and

acknowledgments

We have found that OSTree and Ninja work very well together, thanks to a

neat hack: Using a “ref” (a file in the OSTree metadata

directory) as the target or dependency of a Ninja rule, to track changes to

an entire tree. But most important, I think, is the idea of trees

as first-class citizens in a build system. For researchers, OSTree and

Ninja provide an easy way to explore these ideas. For production, we have

also found OSTree and Ninja to work fantastically well for our use case:

system integrators building container images and rootfs images for embedded

Linux devices.

Most of these ideas (the good ones, at least) are

from my colleague William Manley, who also did most of the implementation

of the build system. I merely wrote it up.

![A Merkle tree, as implemented by OSTree (some details omitted) [Merkle tree for OSTree]](https://static.lwn.net/images/2020/ninja-ost-ostree-objects.png)

![Traditional serial build (left); parallel cacheable operations (right). [Serial vs. parallel builds]](https://static.lwn.net/images/2020/ninja-ost-ldconfig-and-mandb.png)

![apt2ostree stages 1 & 2 [apt2ostree stages]](https://static.lwn.net/images/2020/ninja-ost-apt2ostree.png)