Close to the beginning of Edith Wharton’s 1917 novel, Summer, readers will find a passing reference to “an illustrated lecture on the Holy Land” attended by the novel’s main character, Charity Royall:

What, she wondered, did North Dormer look like to people from other parts of the world? She herself had lived there since the age of five, and had long supposed it to be a place of some importance. But about a year before, Mr. Miles, the new Episcopal clergyman at Hepburn, who drove over every other Sunday—when the roads were not ploughed up by hauling—to hold a service in the North Dormer Church, had proposed, in a fit of missionary zeal, to take the young people down to Nettleton to hear an illustrated lecture on the Holy Land.…11xEdith Wharton, Summer (New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1917), 9.

A few pages later, Charity remarks that she liked the pictures but that the big words the lecturer used confused her, making the outing less fun than it might otherwise have been.

Here, as she often did, Wharton pulled an incidental slice of reality into her novel to add a light touch of ready-made verisimilitude to her fiction. Through a serendipitous entwining of accident and happenstance, I know the identity of the lecturer, the once very popular John Lawson Stoddard, whom she did not see fit to name.

Does knowing the identity of this flesh-and-blood lecturer aid an understanding of Summer, a book that looms with tenebrous plot-line possibilities the more one ponders it? Not really. Does it shed much light on the inner fictive life of Charity Royall that Wharton was just beginning to paint? Hardly. The most one may reasonably claim is that mentioning an illustrated Holy Land lecture added cultural background to Wharton’s literary portrait by alluding to a rich and familiar theme in nineteenth-century British and American fiction. That theme, Christian proto-Zionism, plays in a major key in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876) and Benjamin Disraeli’s Tancred (1847) and in a satirical arpeggio in Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad (1869), to name just a few instances.

Identifying the “Holy Land” lecturer who Wharton popped into Summer, despite that man’s once-outsized and still-lingering fame in 1917, would fail to rate more than a discursive footnote were it not for the fact that this lecturer had a son who, like his father, became a household name, a son who, it happens, would appear in the opening pages of a later novel: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald inserted the son as Wharton had eight years earlier inserted the father, although with a slight twist. While Wharton chose a wholly anonymous approach, Fitzgerald employed a lightly disguised pseudonym in his novel. Soon into the story, one of Fitzgerald’s several ignoble characters, Tom Buchanan, declares:

“Civilization’s going to pieces,” broke out Tom violently. “I’ve gotten to be a terrible pessimist about things. Have you read ‘The Rise of the Colored Empires’ by this man Goddard?

“Why, no,” I answered, rather surprised by his tone.

“Well, it’s a fine book, and everybody ought to read it. The idea is if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged. It’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved.”

The insertions of this father-son duo into American literature by two of the greatest modern American novelists floats somewhere between the salutary and the sublime. It is salutary because the weaving of history and literature bears witness to the truth that only in fiction can some of the deeper patterns of human history and nature be wholly expressed.

It is sublime for two reasons, the first by way of irony. Wharton and Fitzgerald were harbingers and, in a way, prophets of what twentieth-century American modernity would look and feel like. Each made cryptic reference to a man of Brahmin New England stock, the father, John Stoddard, thirty-three years older than the son, Theodore Lothrop Stoddard—appropriately coincidental, since Wharton (1862–1937) was thirty-four years older than Fitzgerald (1896–1940)—who, to understate the matter, were not in the least admirers of the developing qualities of that modernity.

The second reason functions as the third side of the historical-literary triangle here taking shape: Fitzgerald probably did not know or have any reason to care about the identity of Wharton’s “Holy Land” lecturer in Summer, assuming he had read it, when he was writing Gatsby; but Wharton, having received and read a warmly inscribed copy of Gatsby from Fitzgerald on publication, in the spring of 1925, may well have realized that Fitzgerald’s “Goddard” was her lecturer’s son. Wharton answered Fitzgerald with some comments, a few laudatory, one critical, about the book, but the Stoddards, being such a peripheral part of the Wharton-Fitzgerald story, rated no mention. So we cannot know for sure. In that same letter, Wharton used a postscript to invite the Fitzgeralds to tea.22xThe Letters of Edith Wharton, ed. R.W.B. Lewis and Nancy Lewis (New York, NY: Collier, 1988), 481–482. The text of the June 8, 1925, letter is also reprinted in full in R.W.B. Lewis, “‘We Can Still Save Fiction in America,’” New York Times Book Review, April 24, 1988; https://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/24/books/we-can-still-save-fiction-in-america.html.

In any event their personal relationship did not blossom. The tea was captured well by the late Nancy Caldwell Sorel, who noted that two years earlier, when the two writers had been coincidentally visiting the Charles Scribner’s Sons publishing house at the same time, Fitzgerald barged into an office where Wharton was engaged in conversation “and knelt in obeisance at her feet.”33xNancy Caldwell Sorel, “When F. Scott Fitzgerald Met Edith Wharton,” The Independent, December 8, 1995; https://www.the-independent.com/life-style/when-f-scott-fitzgerald-met-edith-wharton-1524911.html. By so doing, Fitzgerald revealed how much he revered Wharton’s art, fame (Wharton became, in 1921, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for literature), and high social connections. Some have surmised that Fitzgerald was particularly influenced by Wharton’s novel The Spark (published in 1924) as he wrote Gatsby.44xSee Michael A. Peterman, “A Neglected Source for The Great Gatsby: The Influence of Edith Wharton’s The Spark,” The Canadian Review of American Studies vol. 8, no. 1 (Spring 1977). So when Wharton invited him to tea at Le Pavillon Colombe, her estate outside of Paris, just after Gatsby was released into the wild, he was both charmed and apprehensive.

Alas, Fitzgerald prepared poorly. After Zelda refused to go lest she be made to “feel provincial,” Fitzgerald took a Wharton family friend, Teddy Chanler, with him. On the drive to Wharton’s residence Fitzgerald forgot to take his own sage advice: “First you take a drink, then the drink takes a drink, and then the drink takes you.” He got hammered, and on arrival started blabbering about a naive American couple in Paris who for three days supposedly mistook a bordello for a hotel. Fitzgerald counted on audacity to charm Wharton, but she expressed only irritation at the lack of narrative granularity—just as she had in her letter of June 8—thus overtrumping Fitzgerald’s attempt at audacity by replying playfully, “But Mr. Fitzgerald, you haven’t told us what they did in the bordello.” As Sorel concluded, so will we: “We are left with Edith Wharton’s version, summed up in her diary: ‘To tea, Teddy Chanler and Scott Fitzgerald, the novelist—awful.’”55xNancy Caldwell Sorel, “When F. Scott Fitzgerald Met Edith Wharton.” In their Letters of Edith Wharton, the editors relate the story of the ill-fated tea, which is mostly likely where Sorel learned of it.

We here behold a wonderfully curious pas de deux of an odd, untouching sort. This enshrouded literary entwining of a father and a son seems a one-off; no other such familial duo has been appropriated into two different American novels without being explicitly named. Both Wharton and Fitzgerald might have both figured out in 1925 what they had together wrought, but at most only one of them did.

That said, coincidences in literature—or, more precisely, across canonical works within a literary tradition—may be less the product of chance than the inexorable but unguided working out of a profound, if barely fathomable, historical logic. When apparent coincidence links the working imaginations of two major novelists of overlapping generations, both astute chroniclers of the American scene as it lurched from the Gilded Age through the Roaring Twenties and on into the Great Depression, then coincidence borders on revelation: Archetypal New England Brahminical families remained throughout this period a class of enormously influential Americans, and to both Wharton and Fitzgerald their presence in American cultural life meant a great deal more than it does to us today in a far more diversely plural America. To know that, and to know it well from a close reading of great literature, is a rare gift that honors those prepared to receive it.

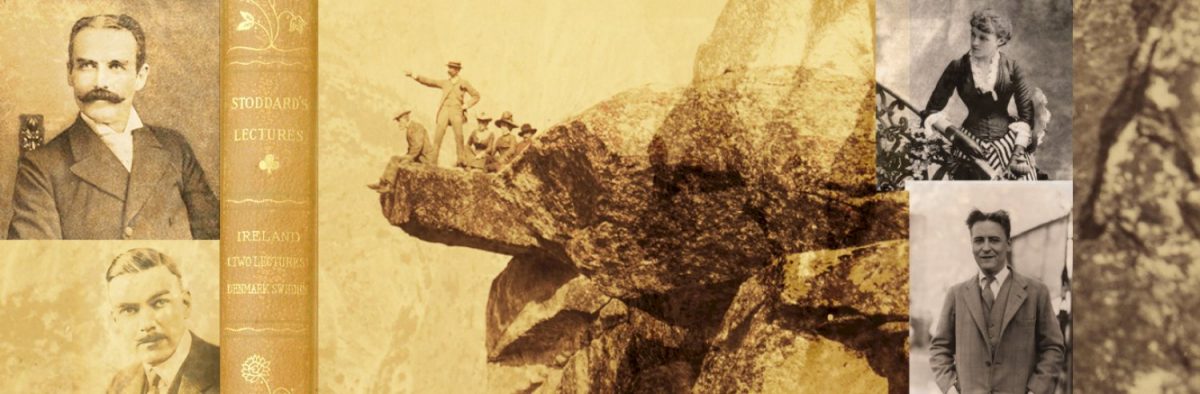

Who Was John Lawson Stoddard?

The “Holy Land” lecturer John Lawson Stoddard was a man who achieved great fame in the latter third of the nineteenth century, just as Edith Wharton bloomed into her youthful prime. Other world-explorer lecturers before him had extended the mid-century tradition of anti-provincialist atheneum lectures, turning the original staid, highbrow affairs into more accessible and entertaining fare. They, too, had employed stereopticon photographs, both black-and-white and sepia, projected onto a screen by means of what was then called a magic lantern. But John Stoddard revolutionized the standard technical setup by using a more powerful light source, a more advanced slide-insertion device, and a textured screen that gave images more optical realism.

Stoddard’s projection equipment was engineered so that the photographs followed one another in tight succession without the long intermediate breaks of blank white light that appeared with older projection technology. His managers had engaged an optics company to produce a projection device that was also far more powerful than any previous one, enabling Stoddard to project huge and vivid images to audiences of several thousand instead of only a few dozen.

The technical refinements made it possible to run through the entire series of images with uninterrupted smoothness as Stoddard delivered his ninety-minute lecture. He never referred directly to the images on the screen. Nor did he use a pointer or in any other way interrupt the flow of entwined words and images. As Stoddard’s biographer Daniel Crane Taylor put it, “one may easily imagine the amazement with which the audiences of 1879 viewed the Stoddard illustrations.… The pictures projected by this new method took on an astounding reality; they appeared as if from nowhere and dissolved into space.”66xDaniel Crane Taylor, John L. Stoddard: Traveler, Lecturer, Litterateur (New York, NY: P.J. Kenedy, 1935), 125.

A decade and a half before the Lumière brothers showed the first motion pictures to the public in 1895–1896, Stoddard’s images had achieved an astounding effect, and, by the time he was thirty years old, he was a celebrity, a lecturer as well as an entertainer. To his visual gimmickry, Stoddard added university erudition (Williams College and Yale Divinity School) and a sonorous voice, and, from 1879 to his retirement in April 1897, his fame grew as his repertoire expanded. He spent about four months each year abroad to acquire photographs and lectured for the rest of year, traveling by train and carriage. In city after city, clutches of what long afterward came to be called groupies followed him, some bringing to lectures large placards of his likeness. Since Stoddard changed the mix of subjects almost every year, in line with his travels, his fans returned time and again to take in his performances.

After Stoddard quit the lecture circuit in the late 1890s, he published his lectures and photographs in a ten-volume set, soon becoming the wealthiest writer in American history up to that point. According to his biographer, the only book outselling Stoddard’s at this turn-of-century moment was the King James Bible. Fame led to an invitation to address a joint session of Congress in 1897, but the gallery overfill was so great that, by popular demand, he repeated the lecture the next day at the nearby Columbia Theater.

John Lawson Stoddard was born in 1850, “Pussy” Jones (as Edith Wharton was known in her pre-wedded youth) in 1862, and Stoddard lectured at least six times in New York City when she was still a young, unmarried woman out and about on the town. During the first few of his fourteen consecutive annual circuits in New York City, Stoddard lectured at Chickering Hall, afterward moving to the new and larger Daly’s Theater. It is estimated that Stoddard lectured to more than one hundred thousand people each year in New York City alone.77xIbid., 190. It is nearly impossible to imagine that the young Edith, who married Teddy Wharton in 1885, did not take in, or least know about, Stoddard’s act. As Taylor notes, his “audiences were mainly composed of the intelligent and cultured business and professional classes in our larger cities.”88xIbid., 190. Strong evidence for the Wharton-Stoddard connection lies in her novella Bunner Sisters, written around 1891 but not published until 1916. In that book, Wharton describes a stereopticon-illustrated lecture presented at Chickering Hall, where Stoddard frequently held forth, although the speaker on that specific occasion was probably Reverend Dr. Newland Maynard, an Episcopal minister from Brooklyn. Wharton’s apparent familiarity with the lesser-known Maynard strengthens the case that she was well aware of the far more popular Stoddard and his illustrated Holy Land lecture, and probably caught Stoddard at or near his maximal fame.

How is it, then, that for many decades now very few even well-educated Americans remember the name of John Lawson Stoddard? Four reasons are likely. First and most important, his fame proved evanescent because technological innovation in visual-arts entertainment soon relegated his projection show to oblivion. Who needs stereopticon lectures when you have silent motion pictures?

The second reason is that Stoddard wandered into what, in retrospect, looks to have been unfair ignominy. Having made a fortune from his lectures and books, Stoddard left New England for New York City around the turn of the twentieth century, remarried in 1901, and then took his bride to live in the Austrian Tyrol. After August 1914, Stoddard openly supported the Austrian and German accounts of the causes of the Great War. Blaming the Russians for starting it and hating the British Empire in general, Stoddard wrote epistles to American audiences accusing the British of shutting off the mail from Central Europe to the United States and of peddling propaganda in hopes of securing American armaments—all of which, incidentally, was true. When the United States entered the war, in 1917, Stoddard fell silent, but not soon enough. The Wilson Administration declared him an enemy, stripped him of his American citizenship, and confiscated all his stateside property and bank accounts. This was not strictly legal, and Stoddard protested, but in vain. Not surprisingly, his reputation at home then dimmed with infamy as well as with distance and time.

Nearly dying from typhus in 1917, Stoddard returned to the God he had abandoned when he left Yale Divinity School before graduating, and he and his wife converted to Catholicism. Stoddard went on to write books about his conversion, but as popular as they were with American Catholics, they held little appeal for the arch-browed leaders of the culturally dominant Protestant Establishment.

Left behind by technology, stigmatized by politics, and shunned by sectarian Christian bias, Stoddard was further jinxed by having a son who would achieve notoriety by promoting ideas that would cause his father no end of disappointment and shame.

Stoddard and his first wife, the former Mary H. Brown, daughter of the mayor of Bangor, Maine, gave life to one child, Theodore Lothrop Stoddard, born June 29, 1883, in Brookline, Massachusetts. The couple became estranged when T. Lothrop, as he later chose to be called, was about five years old, in the middle of the period when his father was traveling for his lecture tours. When John Stoddard left his Massachusetts home for the last time, in 1897, to take up residence in New York City, his son stayed behind with his mother.

Divorcing Mary in 1900 and leaving for Austria the next year with his new wife, Stoddard seems never to have seen his son again. No record exists of John Stoddard traveling back to the United States, nor of T. Lothrop traveling to Europe before his father’s death, in June 1931. If there was any correspondence between father and son—or son and mother—none survives.

In any event, as his father now truly disappeared from his life by putting an ocean between them, T. Lothrop headed in the opposite direction: In 1900, at age 17, he joined the US Army to fight in the Philippines. On returning, he attended Harvard and earned a doctorate in history and a law degree from Boston University. Like his father, whom he strikingly resembled, he turned down university teaching offers to make his own way, soon becoming one of the two or three most prominent propagandists of white supremacy in the United States. He lectured and wrote books, joined the Ku Klux Klan, and even, in 1929, debated W.E.B. Du Bois in what was billed “One of the Greatest Debates Ever Held.” His earlier testimony before the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization helped pave the way for the restrictive Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924.

The Under-Man, Reviled

Given John Lawson Stoddard’s renown, F. Scott Fitzgerald did not have to strain to make it clear who Goddard was modeled on—or to suggest that the title “The Rise of the Colored Empires” was derived from T. Lothrop’s famous 1920 book, The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy.

T. Lothrop’s bigotry was not restricted to people of color. In his 1922 book, The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under Man, he railed against Bolshevism as a movement led by alienated and genetically defective Jews. The book was translated into German, the phrase “Under-Man” becoming Untermenschen. The term, picked up by Alfred Rosenberg, later became a key piece of Nazi propaganda, thus earning Stoddard a place alongside Henry Ford and zoologist Madison Grant as Americans who contributed the most to the race ideology of National Socialism.

Awareness of both the author and his books was near universal among literate American adults when The Great Gatsby appeared. President Warren G. Harding had recommended Stoddard’s 1920 book in a Birmingham, Alabama, speech, and a Saturday Evening Post editorial had urged every American to read it. T. Lothrop’s works were regularly assigned to students at US war colleges during the interwar years as well. Any of Fitzgerald’s readers who managed to miss the connection in 1925 would have lived a very isolated life. Did T. Lothrop Stoddard read Gatsby and recognize himself in the character of Goddard? It would not be surprising if he did. And if he did, he likely would have taken it as a compliment.

Indeed, the younger Stoddard was deeply flattered by the ongoing attention he received for his views, including in Germany, where he spent four months traveling around the country just as World War II was erupting. In addition to meeting with “scientific racism” researchers at German universities and declaring their eugenics theories sound, he also met with Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels, and, briefly, Hitler himself.

Many Americans nodded in agreement, or would have, had they followed T. Lothrop’s comings and goings. Racism and antisemitism were anything but rare in America during the first four decades of the twentieth century. But World War II and the undeniable evidence of the enormities of the Holocaust left a cloud that shadowed T. Lothrop Stoddard’s reputation and that of others who held similar views. Even though he landed a postwar job as an editorial writer for the Washington Evening Star, his death, in 1950, occasioned few obituaries.99xThe Washington Evening Star obituary of May 1, 1950, was the longest, and was literally a whitewash of his ignominious life. T. Lothrop Stoddard fathered two children with Elizabeth née Bates (m. April 16, 1926): Theodore Lothrop Stoddard Jr. (b. 1926) and Mary Alice Stoddard (b. 1928). Neither offspring was dragged into a novel. Like father, like son, then, though the son more clearly deserved his ignominious sendoff.

In Exile and Estrangement

The self-exiled and aging John Lawson Stoddard surely knew of his son’s fame in America. No doubt, too, T. Lothrop Stoddard, then in his early thirties, knew of his father’s voluble defense of the Central Powers and of his subsequent loss of US citizenship. One might suppose that the father’s objectively pro-German views during World War I foreshadowed the son’s pro-Nazi racist and antisemitic views leading up to World War II, but such a supposition would be wrong.

First, John Lawson Stoddard was not pro-German so much as pro-Habsburg and anti-British. If he had any soulful political affections, they were for the Catholic Habsburgs, and, in particular, for the people of the Austrian Tyrol. British imperialism and diplomatic perfidy annoyed him; French fecklessness disappointed him; Italian opportunism during the war outraged him. American hypocrisy—claiming neutrality before entering the war in 1917 but selling arms and ammunition to only one side—offended his sense of honesty and fair play. But none of that elicited any pro-German political enthusiasm. In his earlier travels, Stoddard had spent much time in Germany and become fluent in the language. He seems to have developed a mild fondness for Franconia and Bavarians, but Prussia and Prussians left him cold.

Second, though his son was an antisemite, John was a thoroughgoing philo-Semite. He associated himself with the dispensationalist Anglo-Protestant mysticism of Christian Zionism going back to Lord Shaftesbury, Alexander Keith, and before them to Thomas Brightman in late sixteenth-century Britain. Keith probably coined the famous phrase, “For a land without a people, a people without a land,” in 1843. Shaftesbury took the phrase up and made it famous after the Crimean War.1010xI review all this in Jewcentricity: Why the Jews Are Praised, Blamed, and Used to Explain Just About Everything (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), chapter 2. Stoddard knew it from them—as would most who had attended a Protestant divinity school in nineteenth-century America—and included a near-identical version of it prominently at the crescendo of his most famous lecture of all, the one on the Holy Land that Edith Wharton likely heard. Here is Stoddard’s near-prophetic text—originally drafted for his inaugural 1879–1880 lecture circuit and then updated as events unfolded—as it eventually appeared in print in 1897:

In a place so thronged with classic and religious memories as Palestine, even a man who has no Hebrew blood in his veins may indulge in a dream regarding the future of this extraordinary people. Suppose a final solution of the “Eastern Question.” Suppose the nations of the earth to be assembled in council, as they were in Berlin a few years ago.11That would of course have been 1888. Suppose the miserably governed realm of the Sultan to be diminished in size. Imagine some portions of it to be governed by various European powers, as Egypt is governed by England at the present time. Conceive that those Christian nations, moved by magnanimity, should say to this race which they, or their ancestors, have persecuted for so long: “Take again the land of your forefathers. We guarantee you its independence and integrity. It is the least we can do for you after all these centuries of misery.”

Pausing for effect, Stoddard may have lifted his arms skyward, toward a huge stereoscopic image of the Tower of David, and declared:

At present Palestine supports only six hundred thousand people, but, with proper cultivation it can easily maintain two and half millions. You are a people without a country; there is a country without a people. Be united. Fulfill the dreams of your old poets and patriarchs. Go back,—go back to the land of Abraham.1212xJohn L. Stoddard’s Lectures, Volume Two (Boston, MA: Balch Brothers Co., 1906), 220–221. Originally published in 1897.

These are not the words of an antisemite. So his own son’s virulent antisemitism would have grieved him both for its intrinsic error and for the shame it brought to the family name. It may even explain why John Stoddard sought no contact with his offspring in his twilight years.

It might seem astonishing that Taylor’s biography of Stoddard has nothing to say about Lothrop or his father’s views of his son’s writing—considering that Stoddard died eighteen months before the Nazis came to power and eight years before Lothrop set foot in Europe. Taylor’s was an authorized biography. Stoddard chose him to write it and supplied him with his papers, as Taylor himself explains in his introduction. Subject and author corresponded during the book’s drafting as well. So it cannot be insignificant that, in more than three hundred pages of text, not a single word appears about J.L. Stoddard’s first wife or his son, or that Taylor describes Stoddard’s marriage to his second wife as though she were his first. Edith Wharton would have put such telling omissions to fine use in her fiction.

Even as a Catholic convert living in the Austrian Tyrol, John Lawson Stoddard became an archetypal curmudgeonly New England Brahmin of his era. He thought the ever-advancing technical complexity of life induced superficiality of thought and feeling. He worried that Western culture was giving up on artistic creativity and individualism for the machine-made and the stereotyped. He loathed commercialism in the arts for its eliciting a gravitational pull toward the indecent, regretted what movies were doing to legitimate theater, and believed that the novel, labor-saving devices of his day inspired a lack of respect for work, fostered delinquency, and put honest people out of their jobs.

Generously, one may suppose, Stoddard’s hereditary Puritanism—one of his ancestors was the prominent Congregationalist clergyman Solomon Stoddard (1643–1728/9), the maternal grandfather of Jonathan Edwards—inflected his unremarkable period-specific grumpiness with an austere gold-leaf coating: He thought bridge and other card games were frivolous wastes of time, hated tobacco smoke, and loved dogs. He seems also, as a youth, to have been fond of Maine, an affection that John Updike observed was common among New Englanders, who “all love Maine because it’s so uncomfortable.”1313xJohn Updike, In the Beauty of the Lilies (New York, NY: Knopf, 1996), 462.

It is doubtful that John Lawson Stoddard ever read Summer, even less likely that he read The Great Gatsby. A pity, perhaps, because he would have recognized the allusion to himself in the former as well as to his son in the latter. But maybe it is only another entwining discernible in the warp and woof of culture that some people are destined to become unaware models for the making of great literature, while others are destined to be readers of it.

Portions of this essay were published in the Edith Wharton Review (2024) and appear here in cooperation with that journal.

Reprinted from The Hedgehog Review 27.3

(Fall 2025). This essay may not be resold, reprinted,

or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written permission. Please contact

The Hedgehog Review for further details.