CoreWeave has raised over $25 billion in capital since 2023, mostly debt. The company IPO’d in March 2025 at $40 per share. By the end of Q2 2025, it had $14.6 billion in technology equipment on its balance sheet, including GPUs, servers, and networking gear, and $14.2 billion in debt to match.

The market treats CoreWeave like a high-growth cloud company. The balance sheet tells a different story. Strip away the AI gloss and you’re looking at something closer to a 1990s independent power producer: a leveraged infrastructure vehicle that buys assets with other people’s money and leases them back under long-term contracts.

CoreWeave’s management has executed remarkably well within the constraints they’re operating under. They’ve built a real business serving real customers, including Microsoft, OpenAI, and Meta, at genuine scale. But the interesting question isn’t whether CoreWeave is well-run. It’s why the financing structure looks the way it does, and what happens when that changes.

The answer, I think, is that CoreWeave’s entire business model is arbitraging a market infrastructure gap: the absence of a liquid forward curve for GPU compute. This gap makes GPU financing more expensive than it needs to be, creates barriers to entry for institutional capital, and gives CoreWeave a structural advantage that may prove temporary.

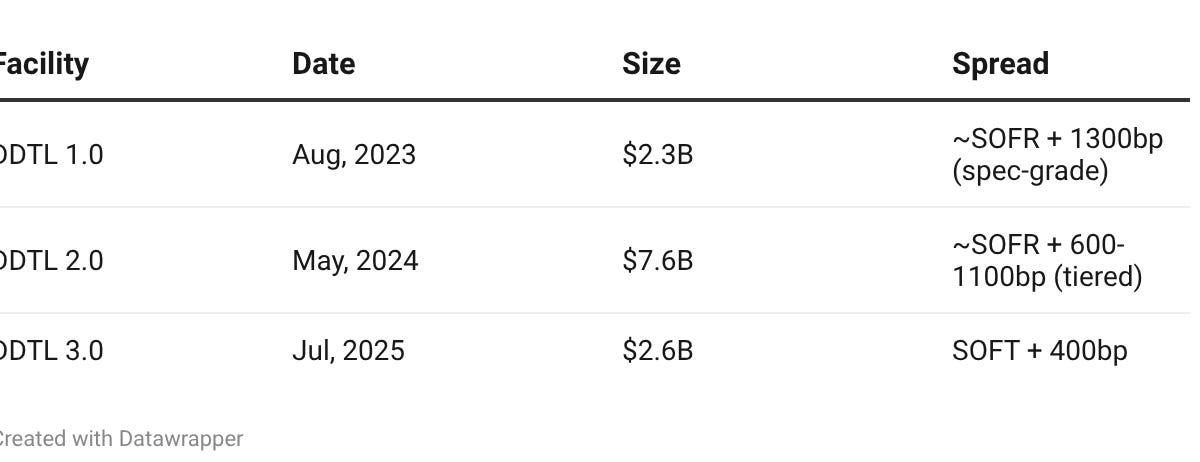

To understand what’s happening, you need to look at CoreWeave’s debt stack. The company has raised capital through a series of Delayed-Draw Term Loan (DDTL) facilities. These are essentially large credit lines secured by GPU hardware and customer contracts, structured through special purpose vehicles (SPVs).

Here’s the progression:

The spread compression is striking. In 18 months, CoreWeave’s marginal cost of debt fell from roughly 15% to roughly 8-9%. That’s progress, but it’s still expensive. Investment-grade corporate debt typically prices at SOFR + 100-200bp. Senior tranches of aircraft Enhanced Equipment Trust Certificates (EETCs) price at 70-150bp over Treasuries.

Why the premium? The lenders in CoreWeave’s deals–Blackstone, Magnetar, Morgan Stanley–aren’t stupid. They’re pricing in real risks: uncertain residual values, rapid depreciation, technology obsolescence, customer concentration. But a big chunk of that spread is something else: an uncertainty premium that exists because the market lacks the infrastructure to price and hedge these risks efficiently.

A forward curve is a set of prices for future delivery of a commodity at different time horizons. When you look up the price of oil, you’re seeing both the spot price and the forward curve: what the market expects oil to cost in one month, six months, two years. This curve does two critical things for asset-backed financing:

-

It provides a benchmark for residual values. If a lender is financing an asset with a 5-year loan, they need to estimate what the asset will be worth in years 2, 3, 4, and 5. A liquid forward curve gives them a market-based estimate.

-

It enables hedging. If a lender is worried that GPU prices might collapse, they can sell forward contracts to lock in future values. This transfers the risk to someone willing to bear it, typically a speculator or a commercial hedger on the other side of the trade.

Aircraft financing has both of these. The International Society of Transport Aircraft Trading (ISTAT) certifies appraisers who provide standardized residual value estimates. There’s an active secondary market for aircraft. Airlines can hedge fuel costs. Lenders can lay off risk.

GPU compute has none of this. Pricing is fragmented and opaque. Different providers quote different rates, and there’s no standardized benchmark. Depreciation is rapid and unpredictable; the H100, Nvidia’s flagship AI chip, saw rental rates fall from roughly $8/hour in early 2024 to $2-3/hour by late 2025. That’s a 60-70% decline in 18 months. No one has financed GPU infrastructure through a full technology cycle, so there’s no track record of how collateral values behave in a downturn.

The lenders in CoreWeave’s deals are essentially being asked to take a view on GPU residual values 3-5 years out without any market-based pricing to guide them. Naturally, they price in a hefty premium for that uncertainty.

How much does the absence of a forward curve actually cost?

I built a simple model comparing two scenarios for financing a 1,000-GPU cluster over 5 years. In scenario A (no forward curve), the lender requires SOFR + 850bp all-in, a 65% loan-to-value covenant, and a 4-year amortization. In Scenario B (liquid forward curve), the lender can hedge residual value risk and prices at SOFR + 200bp, accepts 75% LTV, and matches the 5-year useful life.

The results:

On a $30 million hardware purchase, the absence of market infrastructure adds roughly $4 million in financing costs. Scale that to a $1 billion facility and you’re looking at $130 million in excess interest expense over the life of the loan.

This isn’t speculation. We can observe the spread compression in CoreWeave’s own deals as the market matures. DDTL 3.0 priced 900bp tighter than DDTL 1.0. Some of that reflects CoreWeave’s improved credit profile and contracted backlog. But a meaningful portion reflects lenders getting more comfortable with GPU collateral as they accumulate experience and as price transparency improves.

Here’s where it gets interesting. CoreWeave’s competitive advantage isn’t technology. Plenty of companies can rack and stack GPUs. It’s their willingness to take residual value risk that institutional capital won’t.

When Blackstone lends CoreWeave $7.6 billion, Blackstone isn’t making a bet on GPU prices. They’re making a bet on CoreWeave’s ability to service the debt. The loan is structured with customer contracts as collateral, LTV covenants, and amortization schedules that limit Blackstone’s exposure to hardware value fluctuations. CoreWeave is the one taking the view that they can generate enough cash flow from those GPUs to pay the debt and earn a return on the residual.

In options terms, CoreWeave is writing put options on GPU compute to its lenders. If GPU prices collapse, CoreWeave absorbs the loss. If they hold up, CoreWeave keeps the upside.

The long-term customer contracts–Microsoft through 2030, OpenAI through 2030–are the hedge. They guarantee cash flows regardless of spot market pricing. But these contracts are bespoke, bilateral, and non-transferable. They work for CoreWeave because CoreWeave was early, has operational expertise, and has the relationships to negotiate them. They don’t create broader market liquidity.

This is lucrative now because no one else has built the infrastructure to do it at scale. CoreWeave has first-mover advantage in a market that’s capital-intensive and relationship-driven. But it’s an advantage rooted in market immaturity, not in any durable technological moat.

The market infrastructure is starting to develop. In October 2025, a company called Ornn AI raised $5.7 million to build the first regulated exchange for GPU compute derivatives. They’ve launched the OCPI (Ornn Compute Price Index), tracking H100, H200, and B200 prices across providers. Silicon Data now publishes a daily H100 Rental Index on Bloomberg terminals.

This is early-stage stuff, analogous to where oil futures were in the early 1980s. But if a liquid forward curve does emerge, it creates two possible scenarios for CoreWeave:

-

Validation scenario: The forward curve confirms that long-dated GPU compute holds value. Institutional capital floods in, but CoreWeave’s operational expertise and contracted bacolod give them first-move advantage. They become the blue chip issuer in a new asset class, similar to how Delta and United dominate the aircraft EETC market.

-

Commoditization scenario: The forward curve enables any well-capitalized player to finance GPU infrastructure efficiently. The uncertainty premium that CoreWeave currently captures compresses to zero. Margins decline toward utility-like levels. CoreWeave’s financing advantage disappears, and competition shifts to operational efficiency and customer relationships, which are areas where hyperscalers have structural advantages.

My view is that commoditization is the more likely outcome over a 5-10 year horizon. This is what happened in every other asset-backed market as it matured.

Consider the history of aircraft financing. When EETCs were first introduced by Northwest Airlines in 1994, senior tranches priced at roughly 300bp over Treasuries—wide by today’s standards, reflecting uncertainty about a novel structure. As the market developed benchmarks, appraisal standards, and a track record through multiple credit cycles, spreads compressed to 70-150bp. The airlines that issued early EETCs captured some first-mover benefit, but the structural arbitrage didn’t persist. Today, any creditworthy airline can tap the EETC market at similar terms.

Railcar financing followed a similar path. Trinity Industries’ first securitization in 2003 priced at 80bp over swaps with an Ambac surety wrap—a credit enhancement that wouldn’t be necessary today. As the market matured and investors became comfortable with the collateral, spreads tightened and structures simplified.

GPU compute is earlier in this evolution. But the pattern is consistent across asset classes: novel collateral commands a premium; market infrastructure develops; the premium compresses.

Zoom out and the implications are significant. McKinsey estimates the AI data center buildout will require $4-7 trillion in investment through 2030. Current financing structures add meaningful friction to that deployment.

If the forward curve develops—if GPU compute becomes a hedgeable, standardized commodity—the cost of AI infrastructure capital falls substantially. That’s good for anyone building AI applications. It’s probably neutral to negative for CoreWeave’s margins.

The absence of this market infrastructure is, in a sense, a hidden tax on AI development. Every AI lab paying CoreWeave’s rates is implicitly paying for the market’s failure to develop better pricing and hedging tools. Some of that tax accrues to CoreWeave as excess returns. Some of it accrues to lenders as risk premiums. None of it funds actual compute.

There’s an entrepreneurial opportunity here for whoever builds the infrastructure. Ornn AI is making a bet. So are the data providers building GPU price indices. The capital requirements are modest compared to the market size—futures exchanges are software businesses, not capital-intensive infrastructure plays.

CoreWeave has built a remarkable business exploiting a gap in financial market infrastructure. The gap is real—GPU compute lacks the pricing benchmarks, hedging tools, and residual value standards that make other asset-backed markets liquid and efficient. The opportunity is genuine—CoreWeave has captured it with impressive execution.

But it’s an inherently temporary advantage. Markets mature. Infrastructure gets built. The question isn’t whether CoreWeave will succeed in the near term—their contracted backlog and operational capabilities suggest they will. The question is whether their moat survives the maturation of the market they helped create.

If you’re bullish on CoreWeave, you’re implicitly betting that market infrastructure develops slowly, that their operational expertise creates sustainable differentiation, or that they successfully transition to a more capital-light business model before the arbitrage compresses.

If you’re bearish, you’re betting that the forward curve emerges faster than expected, that well-capitalized competitors replicate the financing playbook, and that CoreWeave’s first-mover advantage proves less durable than it appears.

Either way, the interesting story isn’t the AI hype cycle. It’s the capital structure.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider sharing it with a colleague.

I’m always happy to receive comments, questions, and pushback. If you want to connect with me directly, you can: