How StrongDM’s AI team build serious software without even looking at the code

7th February 2026

Last week I hinted at a demo I had seen from a team implementing what Dan Shapiro called the Dark Factory level of AI adoption, where no human even looks at the code the coding agents are producing. That team was part of StrongDM, and they’ve just shared the first public description of how they are working in Software Factories and the Agentic Moment:

We built a Software Factory: non-interactive development where specs + scenarios drive agents that write code, run harnesses, and converge without human review. […]

In kōan or mantra form:

- Why am I doing this? (implied: the model should be doing this instead)

In rule form:

- Code must not be written by humans

- Code must not be reviewed by humans

Finally, in practical form:

- If you haven’t spent at least $1,000 on tokens today per human engineer, your software factory has room for improvement

I think the most interesting of these, without a doubt, is “Code must not be reviewed by humans”. How could that possibly be a sensible strategy when we all know how prone LLMs are to making inhuman mistakes?

I’ve seen many developers recently acknowledge the November 2025 inflection point, where Claude Opus 4.5 and GPT 5.2 appeared to turn the corner on how reliably a coding agent could follow instructions and take on complex coding tasks. StrongDM’s AI team was founded in July 2025 based on an earlier inflection point relating to Claude Sonnet 3.5:

The catalyst was a transition observed in late 2024: with the second revision of Claude 3.5 (October 2024), long-horizon agentic coding workflows began to compound correctness rather than error.

By December of 2024, the model’s long-horizon coding performance was unmistakable via Cursor’s YOLO mode.

Their new team started with the rule “no hand-coded software”—radical for July 2025, but something I’m seeing significant numbers of experienced developers start to adopt as of January 2026.

They quickly ran into the obvious problem: if you’re not writing anything by hand, how do you ensure that the code actually works? Having the agents write tests only helps if they don’t cheat and assert true.

This feels like the most consequential question in software development right now: how can you prove that software you are producing works if both the implementation and the tests are being written for you by coding agents?

StrongDM’s answer was inspired by Scenario testing (Cem Kaner, 2003). As StrongDM describe it:

We repurposed the word scenario to represent an end-to-end “user story”, often stored outside the codebase (similar to a “holdout” set in model training), which could be intuitively understood and flexibly validated by an LLM.

Because much of the software we grow itself has an agentic component, we transitioned from boolean definitions of success (“the test suite is green”) to a probabilistic and empirical one. We use the term satisfaction to quantify this validation: of all the observed trajectories through all the scenarios, what fraction of them likely satisfy the user?

That idea of treating scenarios as holdout sets—used to evaluate the software but not stored where the coding agents can see them—is fascinating. It imitates aggressive testing by an external QA team—an expensive but highly effective way of ensuring quality in traditional software.

Which leads us to StrongDM’s concept of a Digital Twin Universe—the part of the demo I saw that made the strongest impression on me.

The software they were building helped manage user permissions across a suite of connected services. This in itself was notable—security software is the last thing you would expect to be built using unreviewed LLM code!

[The Digital Twin Universe is] behavioral clones of the third-party services our software depends on. We built twins of Okta, Jira, Slack, Google Docs, Google Drive, and Google Sheets, replicating their APIs, edge cases, and observable behaviors.

With the DTU, we can validate at volumes and rates far exceeding production limits. We can test failure modes that would be dangerous or impossible against live services. We can run thousands of scenarios per hour without hitting rate limits, triggering abuse detection, or accumulating API costs.

How do you clone the important parts of Okta, Jira, Slack and more? With coding agents!

As I understood it the trick was effectively to dump the full public API documentation of one of those services into their agent harness and have it build an imitation of that API, as a self-contained Go binary. They could then have it build a simplified UI over the top to help complete the simulation.

With their own, independent clones of those services—free from rate-limits or usage quotas—their army of simulated testers could go wild. Their scenario tests became scripts for agents to constantly execute against the new systems as they were being built.

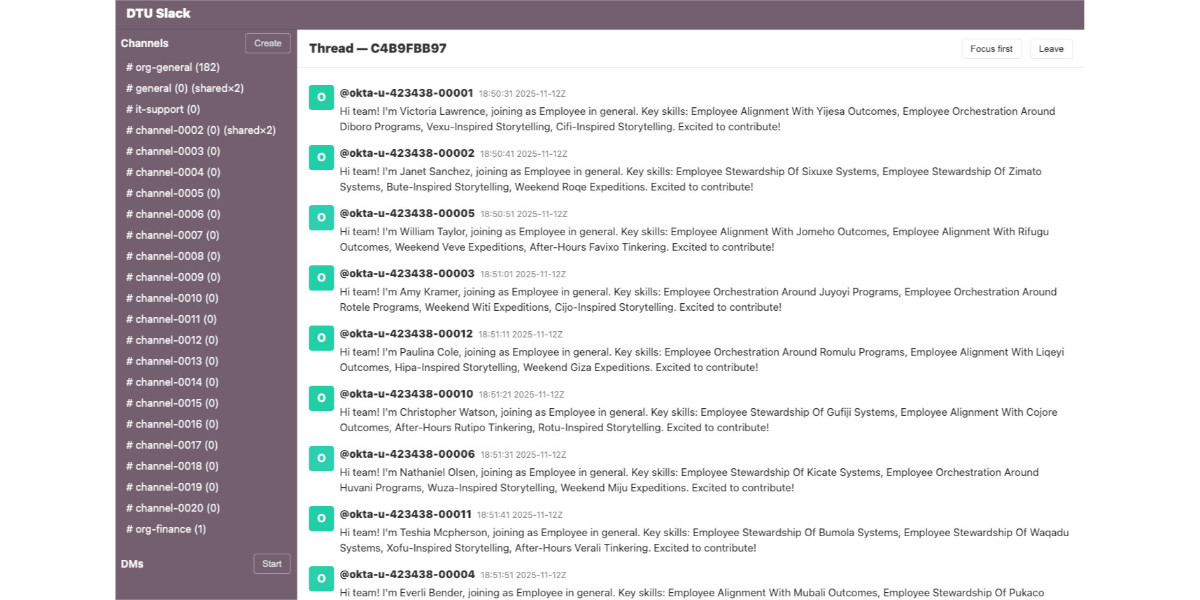

This screenshot of their Slack twin also helps illustrate how the testing process works, showing a stream of simulated Okta users who are about to need access to different simulated systems.

![Screenshot of a Slack-like interface titled "DTU Slack" showing a thread view (Thread — C4B9FBB97) with "Focus first" and "Leave" buttons. The left sidebar lists channels including # org-general (182), # general (0) (shared×2), # it-support (0), # channel-0002 (0) (shared×2), # channel-0003 (0) through # channel-0020 (0), # org-finance (1), and a DMs section with a "Start" button. A "Create" button appears at the top of the sidebar. The main thread shows approximately 9 automated introduction messages from users with Okta IDs (e.g. @okta-u-423438-00001, @okta-u-423438-00002, etc.), all timestamped 2025-11-12Z between 18:50:31 and 18:51:51. Each message follows the format "Hi team! I'm [Name], joining as Employee in general. Key skills: [fictional skill phrases]. Excited to contribute!" All users have red/orange "O" avatar icons.](https://static.simonwillison.net/static/2026/strong-dm-slack.jpg)

This ability to quickly spin up a useful clone of a subset of Slack helps demonstrate how disruptive this new generation of coding agent tools can be:

Creating a high fidelity clone of a significant SaaS application was always possible, but never economically feasible. Generations of engineers may have wanted a full in-memory replica of their CRM to test against, but self-censored the proposal to build it.

The techniques page is worth a look too. In addition to the Digital Twin Universe they introduce terms like Gene Transfusion for having agents extract patterns from existing systems and reuse them elsewhere, Semports for directly porting code from one language to another and Pyramid Summaries for providing multiple levels of summary such that an agent can enumerate the short ones quickly and zoom in on more detailed information as it is needed.

StrongDM AI also released some software—in an appropriately unconventional manner.

github.com/strongdm/attractor is Attractor, the non-interactive coding agent at the heart of their software factory. Except the repo itself contains no code at all—just three markdown files describing the spec for the software in meticulous detail, and a note in the README that you should feed those specs into your coding agent of choice!

github.com/strongdm/cxdb is a more traditional release, with 16,000 lines of Rust, 9,500 of Go and 6,700 of TypeScript. This is their “AI Context Store”—a system for storing conversation histories and tool outputs in an immutable DAG.

It’s similar to my LLM tool’s SQLite logging mechanism but a whole lot more sophisticated. I may have to gene transfuse some ideas out of this one!

A glimpse of the future?

I visited the StrongDM AI team back in October as part of a small group of invited guests.

The three person team of Justin McCarthy, Jay Taylor and Navan Chauhan had formed just three months earlier, and they already had working demos of their coding agent harness, their Digital Twin Universe clones of half a dozen services and a swarm of simulated test agents running through scenarios. And this was prior to the Opus 4.5/GPT 5.2 releases that made agentic coding significantly more reliable a month after those demos.

It felt like a glimpse of one potential future of software development, where software engineers move from building the code to building and then semi-monitoring the systems that build the code. The Dark Factory.