Time crystals, a collection of particles that “tick”—or move back and forth in repeating cycles— were first theorized and then discovered about a decade ago. While scientists have yet to create commercial or industrial applications for this intriguing form of matter, these crystals hold great promise for advancing quantum computing and data storage, among other uses.

Over the years, different types of time crystals have been observed or created, with their varying properties offering a range of potential uses.

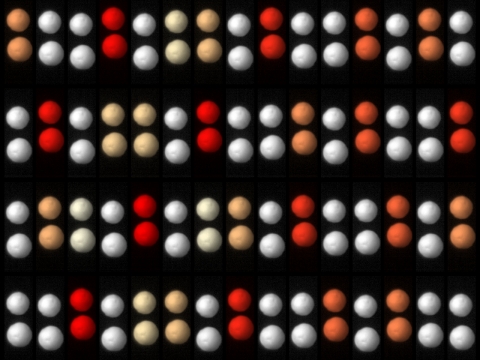

A team of New York University physics researchers has now observed a new type of time crystal—one whose particles levitate on a cushion of sound while interacting with each other by exchanging sound waves. In the process, these particles defy Newton’s Third Law of Motion, which states that for every action of an object, there is an equal and opposite reaction—meaning forces always occur in balanced pairs (i.e., equal in magnitude and opposite in direction). By contrast, in the NYU discovery, the particles, or beads, interact more independently and are not necessarily tied to balanced forces—they move nonreciprocally.

The findings, which appear in the journal Physical Review Letters, expand the prospects that these crystals hold for technology and industry. Notably, these time crystals, which can be seen with an unaided eye, are suspended on a one-foot-high device that you can hold in your hand.

“Time crystals are fascinating not only because of the possibilities, but also because they seem so exotic and complicated,” says Physics Professor David Grier, director of NYU’s Center for Soft Matter Research and the paper’s senior author. “Our system is remarkable because it’s incredibly simple.”

The research, conducted with Mia Morrell, an NYU graduate student, and Leela Elliott, an NYU undergraduate, also offers insights into our biological clocks—or circadian rhythms. This is because, like the newly discovered time crystals, some biochemical networks also interact nonreciprocally—including the way our body works to break down food.