Refrigerators and freezers around the world rely on refrigerants that, when leaked, can emit greenhouse gases thousands of times as potent as carbon dioxide. As the race to find alternative cooling tech heats up, researchers are exploring climate-friendly options such as elastocaloric cooling, a solid-state tech that moves heat through reversible phase transformations.

Now, researchers at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) have announced the first elastocaloric device capable of reaching subzero Celsius temperatures, marking a milestone in the development of this promising refrigeration technology. The desktop prototype, described in a recent Nature paper, successfully froze 20 milliliters of water into ice within two hours, making it comparable to the performance of a domestic freezer.

Elastocaloric systems have attracted attention in recent years because their cooling doesn’t rely on greenhouse-gas-emitting refrigerants. Instead, they exploit the unique phase-transition properties of shape-memory alloys (SMAs). These are a class of metals which, within a specific temperature range, release heat when compressed and absorb heat when relaxed.

But, to date, all research-grade elastocaloric cooling systems have operated at temperatures above 0 °C, seemingly limited by poor performance of the SMAs at lower temperatures.

For their freezer, the Hong Kong team utilized a unique nickel-titanium SMA (51.2 percent nickel, 48.8 percent titanium) that retains its elastocaloric properties at temperatures close to -21 °C. Rods of the alloy were precision-machined to produce thin-walled tubes with a complex inner structure designed to maximize heat exchange.

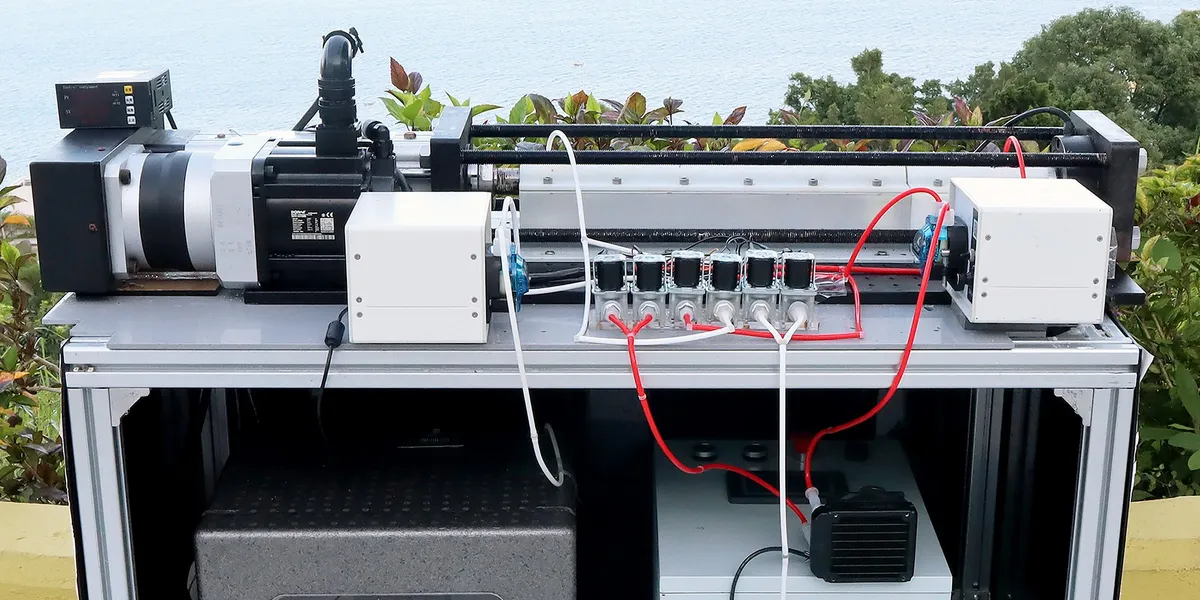

Assembling the Ni-Ti tubes into a working elastocaloric regenerator—a type of heat exchanger—involved grouping them into trios, and tightly fitting them into a strong plastic casing. Eight of these units were connected to each other and a linear actuator was installed at one end of the line to apply the force needed to activate the elastocaloric effect.

The HKUST freezer can turn 20 milliliters of distilled water to ice within 2 hours.Goan Zhou, Zexi Li et al./Nature

The HKUST freezer can turn 20 milliliters of distilled water to ice within 2 hours.Goan Zhou, Zexi Li et al./Nature

How Does the Freezer Work?

In operation, the actuator compresses and holds the Ni-Ti tubes, causing the material to heat up. At the same time, a salty liquid containing calcium chloride (a salt often used to deice roads) is pumped through the regenerator, which carries the heat away and ejects it to the surroundings on exit. Then, the actuator releases, causing the Ni-Ti tubes to rapidly cool down. The fluid flows back through the regenerator in the opposite direction and is cooled by the process.

A full cycle takes 1 second. After 15 minutes of continuous operation in the lab, the cold end of the system reached a record -12 °C while the hot end measured 24 °C, a temperature lift of 36 °C. In real-world conditions—attached to an insulated chamber containing a vial of water, and operating outdoors on a warm day—the system took longer to cool down, with the chamber reaching -4 °C in 60 minutes.

Among the authors of the Nature paper are [from left] Zexi Li, Shuhuai Yao, Qingping Sun, and Guoan Zhou.HKUST

Among the authors of the Nature paper are [from left] Zexi Li, Shuhuai Yao, Qingping Sun, and Guoan Zhou.HKUST

Qingping Sun, a professor of mechanical engineering at HKUST who led the research, acknowledges that there are significant barriers to overcome before this device is ready for commercialization in either domestic or industrial markets. Its energy efficiency is “still lower than conventional vapor-compression-based air conditioning,” with most of the energy loss due to the actuator. “We are developing new actuation technology as part of our system-integration and optimization work,” he says. The team aims to reach lower temperatures too, down to -100 °C, which will require different alloys. And finally, the thin-walled tubular structures are currently made using a precise, but “very expensive” manufacturing process, Sun says. So, they’re exploring alternatives including 3D printing in an effort to reduce material waste and manufacturing costs.

“We are working on these three directions in parallel,” he says, predicting that they’ll have a viable product available on the market in two to three years.

In terms of where an elastocaloric freezer might be used, Sun suggested applications including mobile systems for frozen food delivery and climate control in electric vehicles. He says they have “active collaborations with industrial partners,” but declined to name any specific groups. Long-term, he says, the goal is to “disrupt the existing vapor compression technology market,” but the focus for now is on finding “a niche area to achieve breakthrough, and then gradually expand.”

While elastocaloric cooling shows promise as an alternative to conventional refrigeration without greenhouse gasses, for now it remains firmly in the prototype stage, with substantial engineering hurdles ahead.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web