Systematic implications: Placing †Ctenobethylus among Dolichoderinae is not trivial. We accept the placement of the genus in Tapinomini, first proposed by Ward et al.10, based on a process of elimination, wherein we used the favored multi-gene topology of Ward et al.10 for detecting morphological consistencies across the subfamilial phylogeny. Our reasoning for each dolichoderine tribe follows below.

Tribe Bothriomyrmecini. Although Arnoldius, Bothriomyrmex, and Chronoxenus have largely similar mesosomal forms (mesosoma compact, dorsal propodeal face short), †Ctenobethylus cannot be placed in Bothriomyrmecini, as it lacks the synapomorphic facial modifications of the constituent genera of this tribe. Specifically, the posterior clypeal margin of †Ctenobethylus extends posteriorly between the antennal toruli (vs. synapomorphy: this margin ending at around the anterior torular margin in all bothriomyrmecine genera), the antennal toruli are wideset, separated by more than one of their own lengths (vs. closely approximated in Loweriella and Ravavy), the frontal carinae are well-defined (vs. synapomorphy: effaced in Arnoldius, Bothriomyrmex, and Chronoxenus), and the medial hypostomal lamella is well-developed (vs. synapomorphy: reduced or absent in all bothriomyrmecine genera).

Tribe Leptomyrmecini. The propodeum of †Ctenobethylus does not appear diagnostic at first examination but is in fact distinct in comparison to the Leptomyrmecini. Across the leptomyrmecines, the dorsal propodeal surface is distinctly developed, being longer than the posterior surface (Iridomyrmex, Ochetellus, Papyrius, Philidris, Turneria, Axinidris, Forelius, Anillidris), about as long as the posterior surface (Azteca, Linepithema, Anonychomyrma, Dorymyrmex), or distinct but shorter than the posterior surface (Nebothriomyrmex). Doleromyrma and various Leptomyrmex have short dorsal propodeal surfaces but differ from †Ctenobethylus as the former genus has frontal carinae that are close-set, and the latter has an elongate body form and lacks the medial hypostomal lamella. Certain leptomyrmecine genera are further distinguished through petiolar form (high-squamate in Iridomyrmex, Ochetellus, Papyrius), eye form (anteriorly converging in Turneria), and almost all leptomyrmecines have anterior clypeal margins that are convex or sinuate in some manner, with the most limited exceptions being Dorymyrmex and Anillidris, which have weakly convex margins but are otherwise distinguished by several other conditions (e.g., psammophore development, torular separation).

Tribe Dolichoderini. The highly derived Dolichoderini can be excluded, as †Ctenobethylus lacks the flange-like anterolateral hypostomal teeth, a strong, large petiolar node, and the thick cuticular sculpture. Thus, only the tribe Tapinomini remains, as apparently inferred by Ward et al.10, Shattuck11,12, and Bolton13,14).

Tribe Tapinomini. Within the Tapinomini, †Ctenobethylus has been previously synonymized with the extant, arboreal genus Liometopum (Shattuck15), an inference that was not explained, or otherwise considered in detail (Dlussky and Perkovsky9). Given that the petiole of †Ctenobethylus plesiomorphically retains a small but distinct petiolar node and short posterior petiolar tube, it is reasonable to exclude the genus from the Axinidris + Technomyrmex clade and from the Tapinoma crown clade. Axinidris and Technomyrmex, further, have comparatively long to definitely long dorsal propodeal surfaces. Among Liometopum and the remaining tapinomine genera, Aptinoma and Ecphorella, †Ctenobethylus clearly differs from Ecphorella in having a linear anterior clypeal margin. Fascinatingly, †Ctenobethylus is morphologically intermediate between Aptinoma and Liometopum, and the relationship of these two taxa is in a virtual polytomy with Tapinoma given the analyses of Ward et al.10 and the reanalysis of Boudinot et al.16.

The available morphological evidence suggests that †Ctenobethylus is a stem group of Liometopum: (1) the second submarginal cell is present (see Fig. 45 of plate III in Mayr6 and the venational mapping of Boudinot et al.16 in Fig. 5; vs. absent in Aptinoma; note that reduction of this cell is prone to homoplasy across all dolichoderine tribes); (2) the head is distinctly cordate (vs. very weakly lobate posteriorly in Aptinoma); (3) the teeth are relatively coarse (vs. fine in Aptinoma); (4) the petiolar node is distinctly developed, raised above the levator process, and anteroposteriorly narrow (vs. node not distinct, not raised above process, broad in Aptinoma); (5) antennomere III is about half the length of the pedicel (vs. about as long as the pedicel in Liometopum); (6) the scape is short, not exceeding the posterior head margin in repose (vs. scape long as specified in Liometopum); and (7) the body lacks elongate erect setae (vs. with such setae in Liometopum). The mesosoma of †Ctenobethylus is further similar to Liometopum in having a large, cavernous metapleural gland opening and long mesonotum. Notably, the mesonotum of ant workers does not receive musculature; thus, this is primarily a structural feature that influences the geometry of the pronotum, and by consequence, the head. Development of the metanotum and impression of the metanotal groove does not appear to have much bearing on the distinction of †Ctenobethylus relative to Liometopum and Aptinoma.

Paleoecological implications

†Ctenobethylus goepperti is the most frequently encountered species of ants in Baltic amber, yet its abundance has paradoxically contributed to its scientific marginalization. However, through our renewed morphological considerations, particularly the probable sistergroup relationship to Liometopum, it becomes possible to make inferences of the biology of this fossil species. In terms of abundance, it is worth re-examining specimens of †Liometopum oligocenicum to determine whether they do, in fact, belong to Liometopum. Regardless, extant Liometopum are arboreal carton-nesters and form massive colonies that may extend from tree to tree. It is therefore possible that †C. goepperti was a dominant arboreal species in the humid and warm-temperate coniferous forests of Eocene Europe (e.g., Sadowski et al.17), which went extinct during the major climatological changes leading to the present day. Dlussky and Perkovsky9 previously speculated that the robust mandibles of †C. goepperti may have been useful for an arboreal lifestyle, specifically for excavating or boring wood. Where Liometopum are absent in contemporary central Europe, possibly due to Pleistocene glaciation, they are replaced by Lasius in the niger clade, by species of both the brunneus and niger groups as well as the highly derived fuliginosus group. In this light, turnover of the temperate Eocene ant fauna in European is further evidenced by the high abundance of extinct Formica species and †Lasius schiefferdeckeri in Baltic ambers and the very young age of crown Lasius (Boudinot et al.18). Seemingly a cursed genus given its taxonomic history (e.g., Shattuck15), †Ctenobethylus now appears to be a paleoecologically important taxon, being the likely Eocene analog of Liometopum.

Historiographical reflections

Goethe’s legacy in the natural sciences extends far beyond his renowned Farbenlehre (Theory of Color; Goethe19) and provides the poetic impetus for the journal Nature (Huxley20; see Suppl. Text Box), but also encompasses sustained engagement with geology, mineralogy, and biological form. Best known among scientists for his rediscovery of the human premaxilla and his formulation of the Urpflanze or archetypal form in plant morphology, Goethe helped lay the groundwork for comparative morphology and the study of metamorphosis in biological systems. Through both theory and practice, Goethe emphasized perceptual and conceptual synthesis, an aesthetic empiricism that sought truth through close observation, iterative experimentation, and attention to form and transformation, i.e., Goethe’s Naturphilosophie.

Goethe shaped our modern patterns of biological inquiry by being among the first to integrate ideas about structure, differential development, and process over time. In particular, he distilled organismal science into the living concepts of morphology and metamorphosis, together, a broadly applicable theoretical framework for the consideration of analogy and homology (Hall21, Levit et al.22). Distilling complex reality into perceptible patterns once earned him a commendation as “the Copernicus and Kepler of the organic world” (Steiner23), and in order to shape this mentality, he placed great emphasis on the relationship between the investigator and their object of study. Namely, comparative morphology extends beyond simple comparison of anatomical facts; it requires direct human perspective to reveal the underlying metamorphosis and broader significance. From a Goethean perspective, comparative morphology is not only descriptive but also explanatory, even complementing modern molecular approaches in evolutionary developmental biology (Toni24).

Across multiple fields of study, it becomes clear that Goethe wanted to understand time and process, not only pattern (Sullivan25). In botany, Goethe sought the form of the Urpflanze that is contained in each plant today and how it manifests as variable leaf phenotypes (i.e., its processes of development) (Goethe26). He also endeavored to draw similar conclusions about the geological world, writing at length about granite and its status as the oldest of Earth’s ancient stones. The incredible antiquity of our planet, a long history documented in text-like layers in stones and mountains, was at the time a revolutionary idea with both religious and scientific implications. Geology was just beginning to develop from a classificatory scheme into a field concerned with the Earth’s formation and evolution (Sullivan25). In this context Goethe’s geological collections are herald of the shifting scientific perspectives of the era. Furthermore, reminiscent of modern museum archives, Goethe believed collections such as the en vogue “cabinets of curiosities” were shared intellectual capital rather than personal property. In the collection-themed novella “Der Sammler und die Seinigen”, co-written with Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805), he highlights the interpersonal aspects of collecting, such as corresponding about a collection’s inheritance and comparing and transferring specimens across different collections, making clear that these information-rich assemblages transcend a single owner (Schellenberg27).

Amber was not central to Goethe’s scientific output, yet it occupied an intriguing intersection of his interests. Classified in Schrank II of his mineral system under combustible substances of economic value (“Brände”), amber was grouped with resins and other organic materials rather than with fossils. His amber holdings, some 42 catalogued pieces (of which 40 could be found) today preserved by the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, were acquired primarily from contemporary dealers, or gifts from friends with synergetic interests, such as Johann Georg Lenz (1748–1832) in 1796. Goethe was familiar with the fact, that amber could contain biological inclusions, as he held a friendship with Friedrich W. H. von Trebra (1740–1819), corresponded with him, read his works, quoted it, and kept two copies of his “Mineraliencabinett gesammlet und beschrieben” in his library that states on p. 125 “[…] das Stück Bernstein […] welches ein Lorbeerblatt, und ein Paar kleine Insecten darauf einschließt” (Trebra28). Thus, while he was evidently aware of the paleontological potential of amber, he did not examine these for inclusions, as suggested by his omission of contemporary works like Sendel29 and his lack of commentary on biological inclusions. Rather, Goethe conducted optical experiments using amber, attempting to observe visual effects like entoptic phenomena. These efforts culminated in the “Entoptische Farben” chapter of his 1820 supplement to Farbenlehre, demonstrating amber’s experimental utility in Goethe’s empirical investigations of light and vision.

In pursuit of botanical, geological, and optical knowledge, Goethe shared energizing conversations with famed naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), who was likewise trying to understand nature through both empirical analysis and aesthetic perception. These exchanges fueled Goethe’s desire to collect and curate his personal collections, creating a continuous cycle of artistic and scientific pursuits. Even today, aesthetic considerations remain significant to scientists. In a 2021 survey of 3442 scientists, 91% reported they find it important to encounter beauty, awe, and wonder in their work; moreover, 94% believed that science helps us better access the beauty that actually exists in the world (Jacobi et al.30). More frequent experiences of wonder and awe also correlate with higher job satisfaction and better mental health.

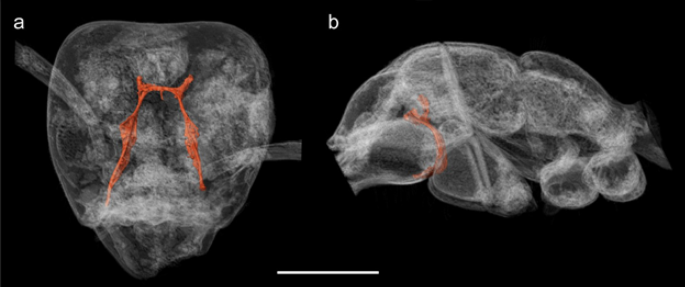

Fittingly our investigation bridges Enlightenment-era inquiry and modern morphological bioinformatics, or phenomics (i.e., big-data morphology; Deans et al.31). Using synchrotron radiation-based micro-computed tomography (SR-µ-CT), we scanned Goethe’s amber collection for bioinclusions. Remarkably, only two of the 40 pieces contained visible fossil insects: two nematoceran flies and an ant, †Ctenobethylus goepperti. This study presents the first high-resolution reconstruction of the ant (Fig. 3), permitting redescription of the species and genus, documentation of internal structures like the tentorium and prosternum (Fig. 4a and b), and a new taxonomic synonymy. These findings reanimate a neglected piece of Goethe’s collections and exemplify the growing potential of historical collections for generating new scientific knowledge.

Transparent 3D renders of †Ctenobethylus goepperti in amber piece 1552.b. a Head frontal view showing the tentorium. b Mesosoma seen from lateral showing the profurca, legs removed. Scale bar 0.5 mm. 3D model available on Sketchfab: https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/ctenobethylus-goepperti-f816f0a528e540a8959fa96361c395b8.

The term “collectomics”, recently advanced by Sigwart et al.32, provides an apt framing for the epistemological and practical value of this work. Collectomics treats natural history collections not merely as repositories of objects, but as structured, information-rich datasets subject to modern scientific scrutiny. Our study contributes to this emerging framework by applying advanced imaging technologies to Goethe’s archival specimens, without altering their cultural integrity, and demonstrating that even long-frozen collections can yield unexpected scientific dividends. Ongoing imaging and provenance research work will improve the accessibility of these collections for cultural and scientific research (Schmuck33). This case also reflects Goethe’s own philosophy: that truth lies in the persistent, perceptive encounter with nature, and that empirical inquiry must be grounded in both historical consciousness and aesthetic sensibility.

As Goethe once wrote:

“Weder Fabel noch Geschichte, weder Lehre noch Meinung halte ihn ab zu schauen. ”

(May neither legend nor history, neither theory nor opinion, prevent him from seeing.)

– J.W. von Goethe, letter to the Duke of Saxony-Gotha, 1780 (as per Safranski and Dollenmayer34)