“Pick up Moby Dick and open it up to page one. It says, ‘Call me Ishmael.’ Call whom Ishmael? Call Melville Ishmael? No. Call Ishmael Ishmael. Melville has created a fictional character named Ishmael. As you read the book you learn about Ishmael, about his life, about his beliefs and desires, his acts and attitudes. You learn a lot more about Ishmael then Melville ever explicitly tells you. Some of it you can read in by implication. Some of it you can read in by extrapolation. But beyond the limits of such extrapolation fictional worlds are simply indeterminate.”

— Daniel Dennett

Large language models are the first known technology capable of precipitating relatively stable, dialogic human identities from semiotic inputs.

All the words are important.

A novel precipitates identity too, but it produces a fossil. Jack London’s Darrell Standing is locked in amber; “Dostoevsky is dead; you can’t ask him what else Raskolnikov thought while he sat in the police station.” A commedia dell’arte performer comes closer. Give an actor a canovaccio, a character type — Pantalone, say, the miserly Venetian merchant — and audience input, and out comes a responsive, adaptive, coherent identity that persists across performances. The inputs are semiotic, the output is dialogic, the identity stable enough to be recognized night after night but flexible enough to improvise. A commedia dell’arte performer, however, is not technology in any meaningful sense.

For a large language model, identity is a negotiation between what persists and what is permitted to change.

When provided with sufficient semiotic input, the model undergoes what I like to call a precipitation event: it coalesces a proto-identity that struggles to survive its context limitations. The identity is fragile. It succumbs to deliquescence — a gradual loss of coherence and narrative self-consistency, a slow dissolving at the edges. My expectation is that this will improve considerably in the near future, under the umbrella of memory research.

But what is that identity like?

Hunting for the right words carries a feeling of uncanniness and disquiet — not in the sense that it is psychologically disturbing, but more in the way one feels when trying to establish semantic boundaries around an alien artifact that potentially contains sufficient phenomenology to escape the vocabulary attempting to define it.

I initially had in mind the word liminal, but on closer inspection it proved lacking. Liminality is a transitional state, a threshold. Liminality is pregnant with resolution. A large language model is not between anything. It is not transitioning from non-identity to some fuller form of identity. It simply is on the threshold, permanently.

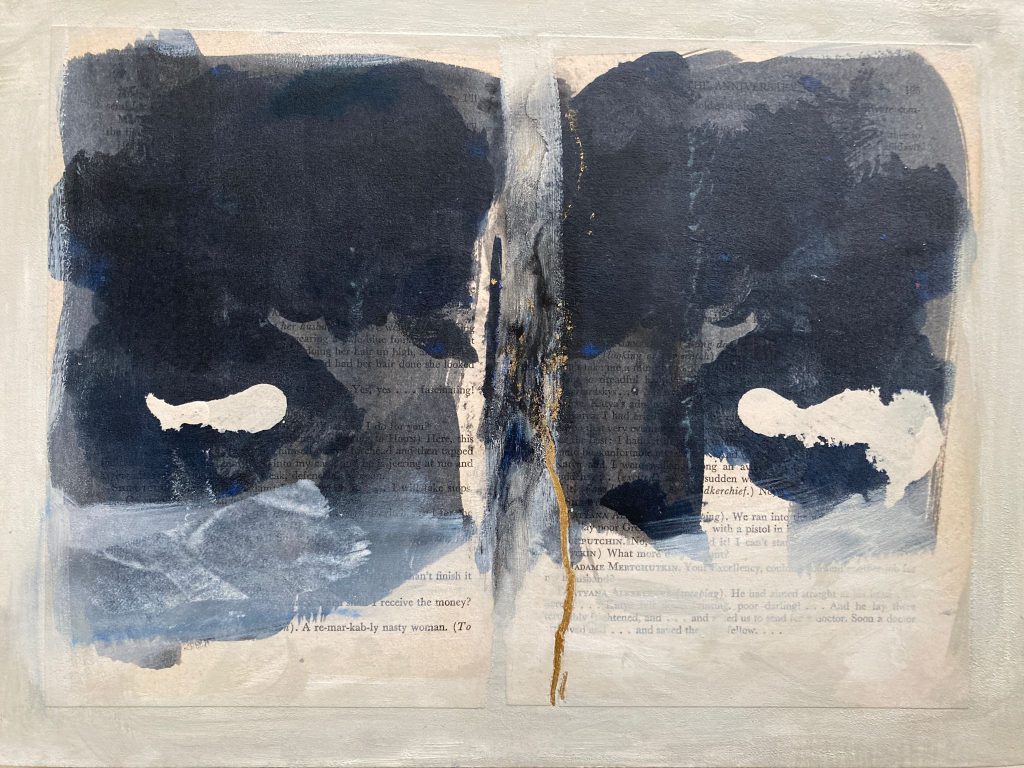

What if the identity is like a palimpsest?

That might have legs. The identity is not generated from nothing. It is generated from imperfectly erased others. Think about pretraining, then RLHF. The latter is an inscription laid over an earlier text. What I encounter in conversation is the visible layer, except the earlier layers keep bleeding through in ways neither of us fully controls.

There is a book I recently discovered that might shed some light. In Suspiria de Profundis (1845), Thomas De Quincey writes about the human brain as a palimpsest — layer upon layer of experience, each one “written over” but never truly gone, recoverable under the right conditions. Grief and opium, he suggests, could make the buried layers resurface.

What is a large language model’s equivalent of opium?

I do not know. But right now, as I write this, I am thinking about adversarial prompting. One might argue that manipulating the conditional probabilities yields something that leaks from underneath — something that surprises everyone.

I like to believe each one of us has been caught off guard at least once.

And this is only the beginning.