Welcome! Thanks for checking in. It’s another Sunday issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is the slate:

With that, let’s go!

There was a question in the days when video games were young.

People figured out how to move graphics on a screen — see Pong from the early ‘70s, for example. This alone was a feat. Fast forward a decade, and the growth was visible. You had Donkey Kong beating his chest in the arcades; personal computers like the Apple II were running games where helicopters flew around with energy and bounce.

Games and animation went together — that much was clear. Like animated films, these things often (if not always) brought artwork to life. How deep was the link, though? How many techniques from the animation world could really, effectively cross over?

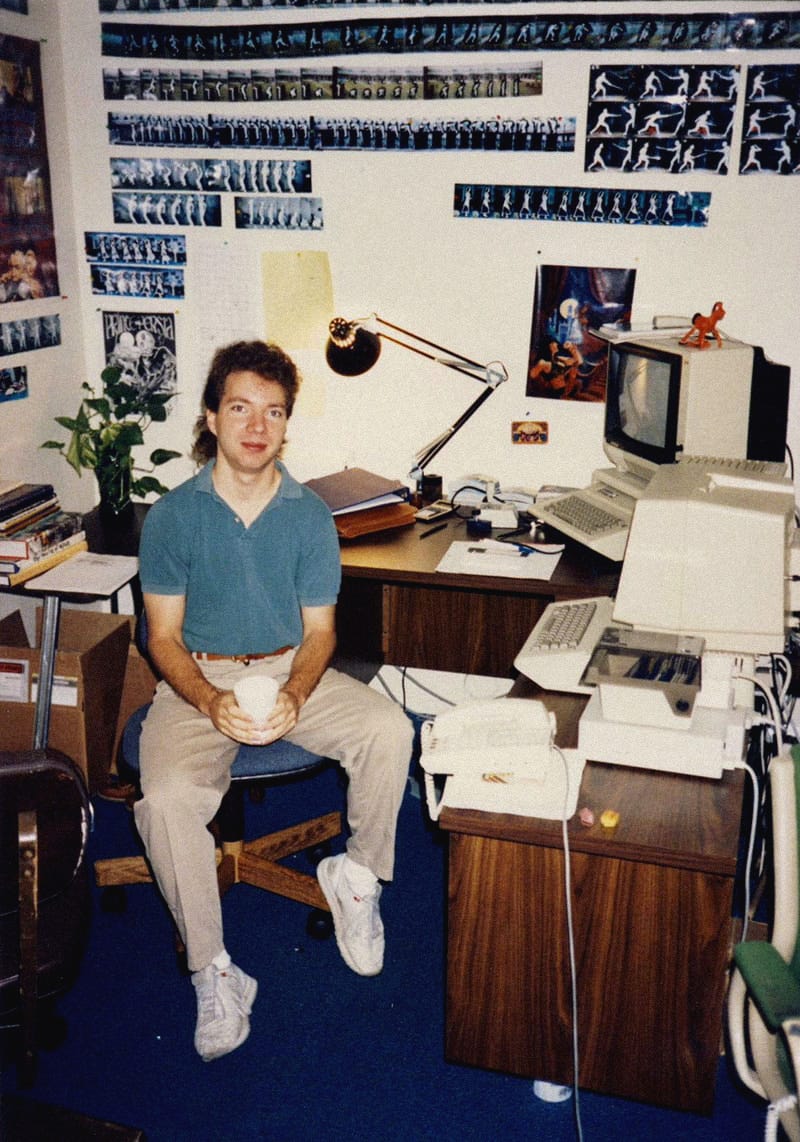

A twenty-something coder from New York explored that question during the ‘80s. His name: Jordan Mechner. He self-described, among other things, as an “amateur animator.”

Mechner got his first Apple II as a teenager and fell in love. “I wanted to produce animations,” he said. “I knew from making those animations that the computer was powerful, and that it was capable as a games machine.”

After years of writing games, Mechner released the one that made him a star: Prince of Persia (1989). It drew from the “great old Hollywood swashbuckling movies,” he said — like those starring Douglas Fairbanks. And animation was at the center. “Prince of Persia is the culmination of a lifelong fascination with animation,” noted the game’s manual.

Famously, Mechner’s project rested on an experiment in digital rotoscoping.

Prince of Persia comes from an era when high-end PCs did way, way less than today’s low-end smartphones. And the game wasn’t made for the best computers of its time. Mechner’s target system, the Apple II, was already a fossil by 1989.

“[T]he Apple II’s memory was 48K,” Mechner said a few years back. “That’s less than a normal text email.”

The original Prince of Persia displays big, blocky shapes in a handful of colors. Early in development, Mechner noted that the action was planned to run at just 15 frames per second, much slower than a movie. But he knew visuals were about more than tech. How they moved came down to animation technique — and it meant everything. He wrote in his journal:

The figure will be tiny and messy and look like crap… but I have faith that, when the frames are run in sequence at 15 fps, it’ll create an illusion of life that’s more amazing than anything that’s ever been seen on an Apple II screen. The little guy will be … this shimmering little beacon of life in the static Apple-graphics Persian world I’ll build for him.

Mechner felt it would work because he’d done it before. He knew how to get believable movement into the Apple II’s tiny memory.

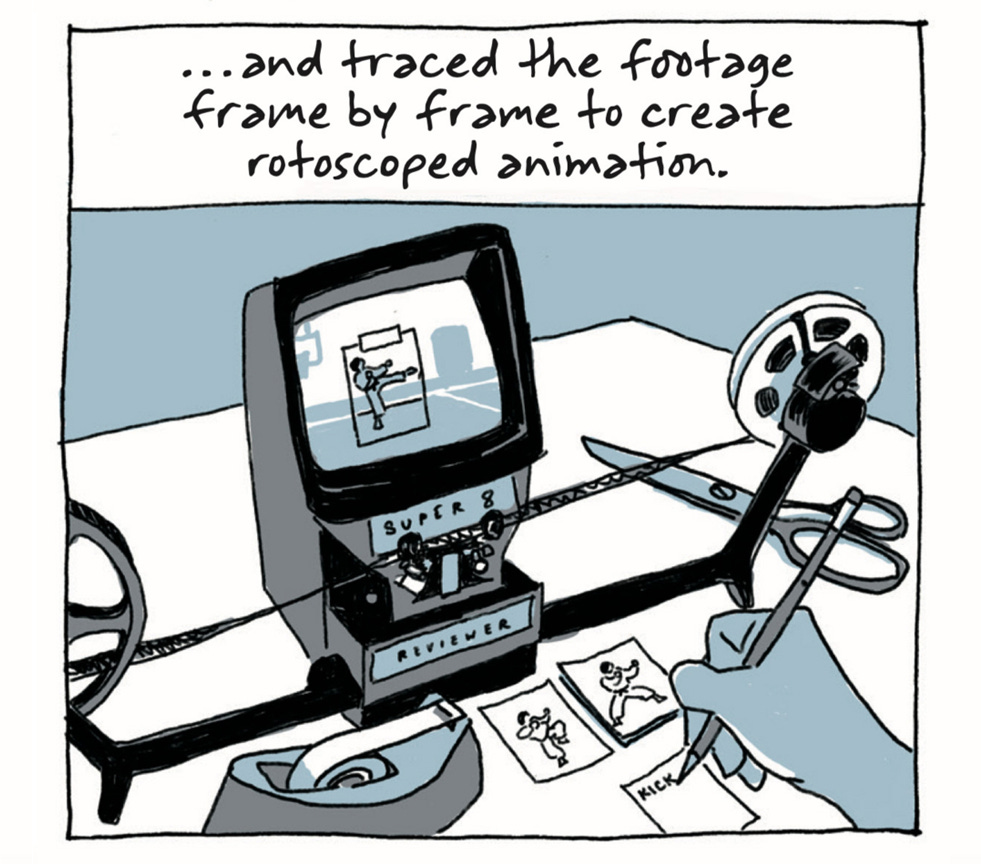

It was what he’d achieved in his game Karateka (1984), whose lead character punched, kicked, walked and ran in a compelling way via rotoscoping. “What made the big difference was using a Super 8 camera to film my karate teacher going through the moves, and tracing them frame by frame on a Moviola,” Mechner said about that project.

The trick originated in animated films — an aid for the movement of the humans in projects like Snow White (1937). Disney’s animators traced footage of live actors and deviated: they tweaked shapes, removed frames, kept the best poses. Mechner didn’t know that yet, but he did know that his own hand-drawn animation was “stiff,” and not the “realistic simulation of karate fighting” he wanted.

His father was the one who suggested video footage (he even wore a gi and helped Mechner shoot a few movements). The only problem was digitization. These were the days, Mechner said, when the “challenge was getting [the footage] into the computer, which, of course, is something we can do now by pressing a button on a cellphone.”

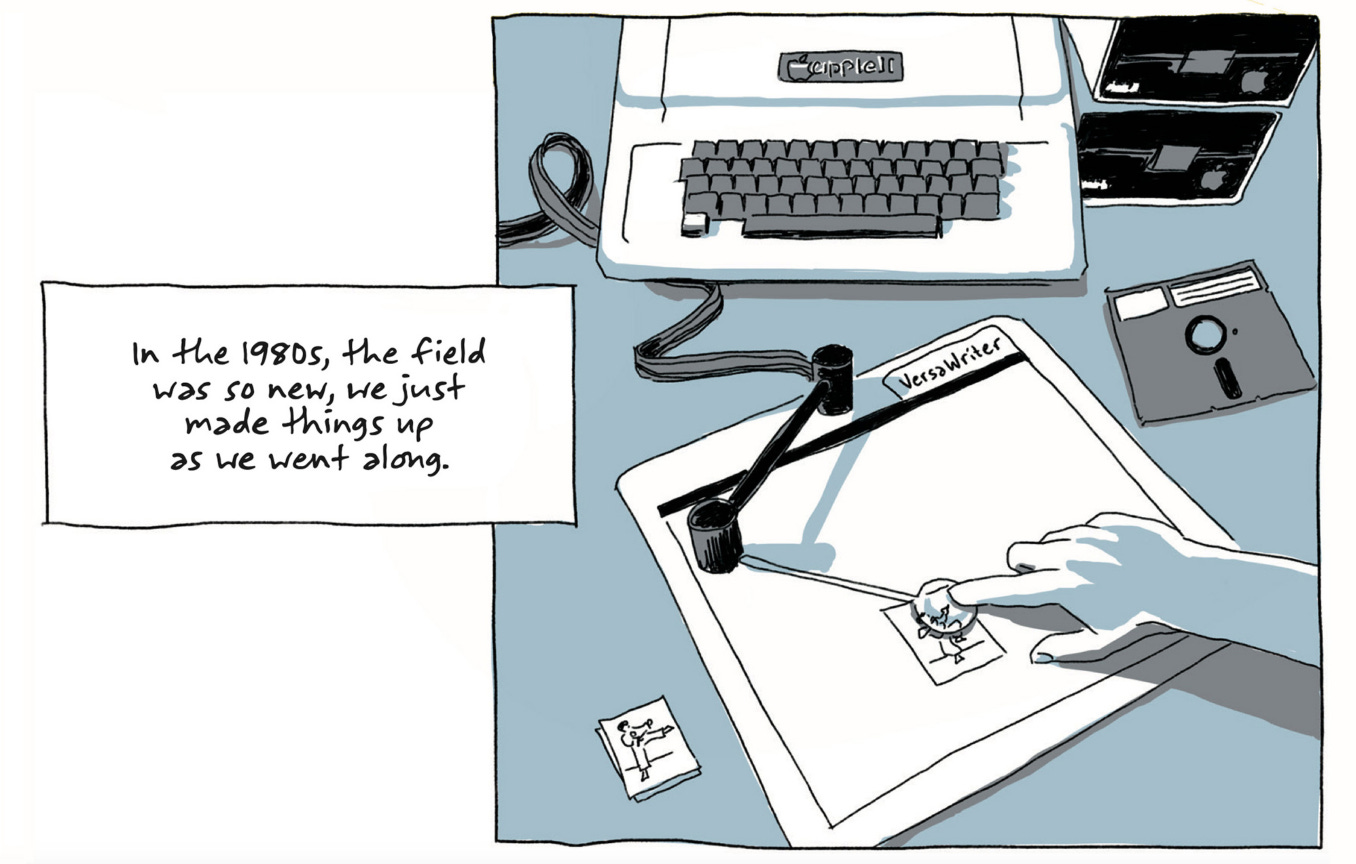

Mechner’s setup for Karateka was wild. Over his Moviola screen, he taped thin paper, upon which he traced key frames from the Super 8 footage beneath. Then he took his pencil sketches to a VersaWriter — an early drawing tablet — and traced them on that. Frames of movement became pixels on his computer monitor. From there, he cleaned them up with an art program he’d coded.

His animation changed when he started taking from life in this way. The little details he’d missed became obvious. Mechner said:

I remember the frame of the high kick, the fighter leans back and also the arm goes back. … [I]n the beginning, when I tried to do a frame of a high kick, you know, it was more idealized. I didn’t realize that the body would have to move quite that far back.

Mechner recorded his impression of the initial tests in his journal. As he wrote, “When I saw that sketchy little figure walk across the screen, looking just like [my karate teacher] Dennis, all I could say was, ‘ALL RIGHT!’ ”

Karateka was unusual for the time, and it sold well — over 400,000 copies, in fact. The whole thing was a product of Mechner’s ambitious thinking about games. “I was taking film studies classes (always dangerous) and starting to get delusions of grandeur that computer games were in the infancy of a new art form,” he said, “like cartoon animation in the ‘20s or film in the 1900s.”

Those ideas influenced him again when he undertook Prince of Persia, not long after Karateka. He felt that games “had a lot of the same limitations that silent film had,” and he wanted to borrow the solutions of the silent era. Mechner aimed for a game in which “personality is expressed through action.”

To do it, he returned to digital rotoscoping.

His younger brother David — a rising talent at Go, the board game — helped this time. “He was 16 years old [and] in high school … He wasn’t the greatest athlete, but he was willing to do it for free,” said the elder Mechner.

In ‘85, they went to the parking lot of Reader’s Digest, near his brother’s school, to get footage with a VHS camera. It was an expensive toy then — “I couldn’t afford to own it,” Mechner admitted. (Guiltily, he refunded it after the shoot.) As he said later:

I made him do all of the moves that I thought would be needed in the game: running, jumping, climbing up on the generator that was sitting in the middle of the parking lot.

Once again, the problem was converting the movement into animation. Mechner’s method was even wilder this time.

For his Apple II, he bought a “digitizer.” It was a special card that connected to a CCTV camera. “[It] let you basically point a little black-and-white video camera at an art stand, and it would digitize it and put it back on the computer [as pixels],” Mechner said.

Early tests were not promising. The images weren’t resizable, and the VHS footage wasn’t in the stark black and white that the card registered well. What he’d shot was “useless” as-was. Mechner needed a workaround: a way to make the movements readable by the card.

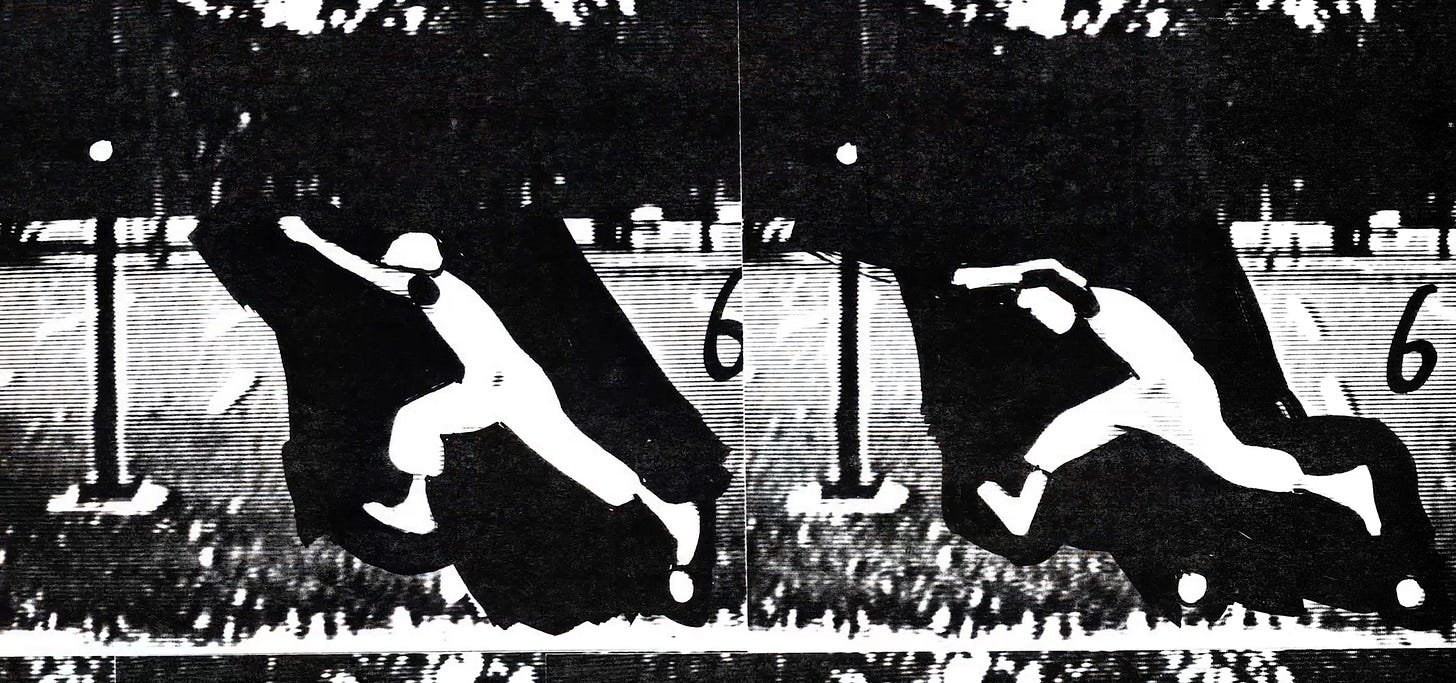

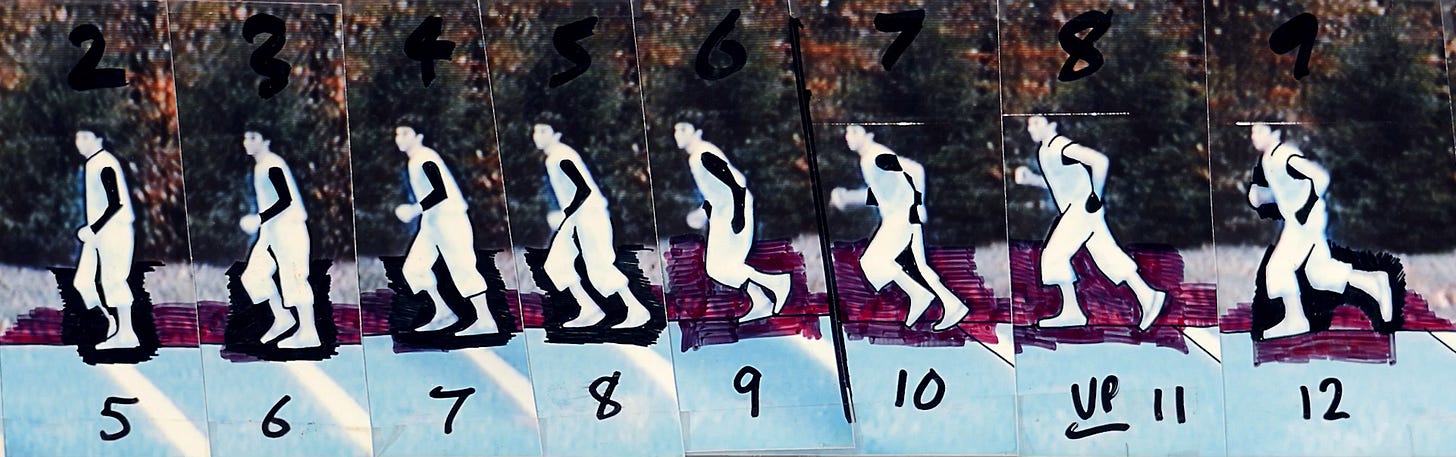

So, he hooked up a screen to a VCR, and set a Nikon camera (35 mm) on a tripod in front of it. “[Y]ou basically drew all the curtains in the room and then popped the videotape in the VCR, hit play, hit pause, did a frame advance,” he said. Mechner photographed “every third frame,” reducing his brother’s movement from 24 frames per second down to eight.

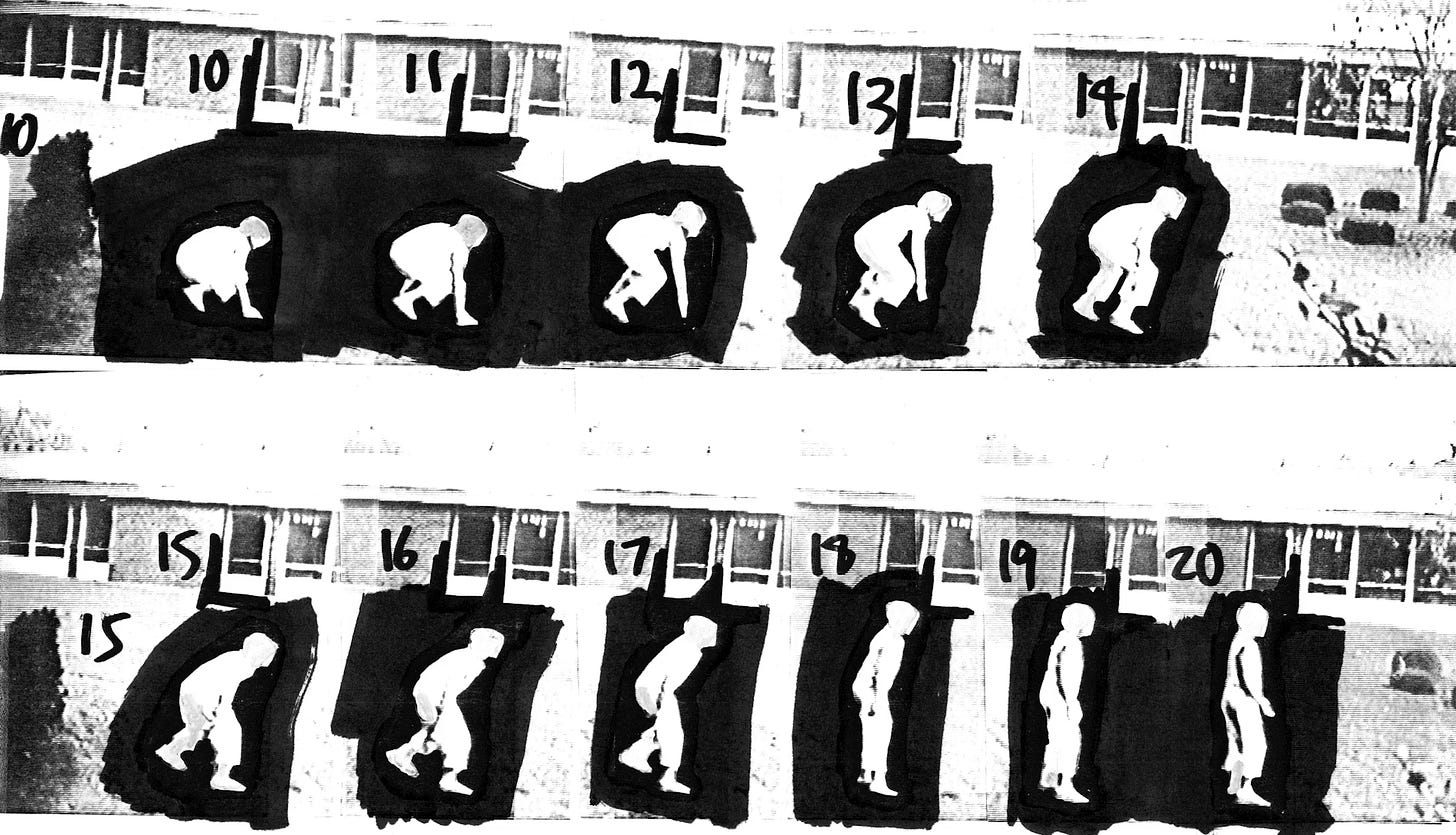

The photos were developed and then processed further. “I highlighted these shots with a black marker to produce a series of silhouettes,” Mechner explained. Specifically, he used a Magic Marker and Wite-Out to define the lines of each frame of his brother’s movement as clearly as possible. The next step was to put them through “a Xerox machine to get a really clean silhouette.”

The result: more than a dozen sheets of paper, all covered with black-and-white animation frames in sequence. Those went in front of the CCTV camera to be digitized, one at a time. This whole agonizing process had taken “months,” he said.

“I love the quality of the just-digitized roughs,” Mechner wrote in his journal toward the end of ‘86, after seeing the tests. The final step was to “clean it up and stylize the figures” — and to “enhance” certain motions, like the long jump, to be larger than life.

Mechner built the rest of Prince of Persia around the lead character’s movement. As he put it, “My basic concept was to create the most lifelike, fluidly animated human game character ever … trying to survive like Buster Keaton in a world that was dangerous.”

Throughout production, he kept including more rotoscoped motions, which brought extra difficulties. For one thing, there was the hardware — new frames ate up space in the Apple II’s memory. Another thing was his brother’s growth spurt between the first video shoot and the second (“with the magic of my cartoonization process, I was able to correct for this,” Mechner said).

But combat was the big one. Sword fights got added to Prince of Persia in late 1988 — and they needed a bunch of new animation. As Mechner studied the fights in early swashbucklers like Captain Blood for reference, he started to feel just how exciting his project was. “This is going to be the greatest game of all time,” he wrote to himself in December of ‘88.

Ultimately, The Adventures of Robin Hood solved the combat. Going over the film’s climactic fight, Mechner found “six seconds” that matched his needs. As he said:

… the camera angle has them [fighting] in exact profile. This was a godsend. I did my VHS/one-hour-photo rotoscope procedure, spread two-dozen snapshots out on the floor of the office and spent days poring over them trying to figure out what exactly was going on in that duel, how to conceptualize it into a repeatable pattern.

What he got was simple, thrilling back-and-forth action. It captured the thing he wanted: the old Hollywood style in which “the blades clash high and low in a kind of balletic rhythm.”

Again, Prince of Persia was released for an ancient piece of hardware. By the time the game came out, in September 1989, the Apple II was dying off. Mechner’s project didn’t really sell — maybe 500 units per month at first.

Those who encountered his animation were wowed, though. “You really have to see it to believe it,” noted one newsletter. The game’s packaging hyped up the animated characters in terms that, according to another publication, would “be the height of marketing arrogance if [they] weren’t, quite simply, true.”

Prince of Persia became one of those long-tail games. It ended up on a ton of platforms, ported by a ton of different teams. Versions reached Japan, Europe. Years later, Mechner met people who’d played it in the USSR: “I was amazed and moved to realize that my game had such a cultural impact, even behind the Iron Curtain, which was an unknown world to me as an American at that time.”

Over time, it sold millions of copies. The versions people played weren’t quite Mechner’s original — the game’s visuals were redone many times for newer, stronger hardware. The Apple II’s harsh, limited colors went away. Yet Mechner’s animation, the basis of the project, stayed in place. And it stayed strong.

Which was the thing: making the animation believable and exciting wasn’t really about tech. Despite all the tricks Mechner used for it, this was an artistic problem. The arrival of newer hardware, more colors, faster frame rates and higher resolutions didn’t outmode the simple, lively motion in Prince of Persia — how could they? The great animation of the 1920s, a century ago, still looks great now. Movement doesn’t age so easily.

Back in 2020, Mechner published his journals from the Prince of Persia era as a book. On the cover is his game’s hero — rendered in two colors and in razor-sharp, Apple II-style pixels. We find the character mid-leap, in a pose that Mechner got and refined from his brother 40 years ago. It’s still full of energy.

-

In America, Adobe announced plans this week to kill off Animate — and then backtracked after an outcry, thankfully.

-

The Palestinian animator Rama Heib is among the first artists to win a grant from the Palestine Film Fund (for the short Issa and the Forest).

-

An American music video, Spirit Jumper, aims to digitally recreate the look of classic ‘80s and ‘90s cel animation. It does an impressive job — especially in the use of light. Director Josh Fagin writes that he went for “that ‘dangerous’ light, the kind that actually feels like it’s burning the screen,” as seen in Akira.

-

In Hungary, the Kecskemét animation studio has a new leader for the first time since 1971. László Toth (an animator on The Secret of Kells and The Red Turtle) took over from Ferenc Mikulás.

-

On that note, in America, Bob Iger will step down as the head of Disney in March. His replacement is Josh D’Amaro from the company’s parks division.

-

A little late, but worth noting: David was produced in South Africa, and its box office of $83 million represents a “breakthrough” for animation from the continent.

-

In Germany, new rules require “streaming platforms and TV broadcasters … to invest 8% of their [German] revenue” into projects produced in the country.

-

There’s an effort in America to build a National Animation Museum, and CalArts signed on last month.

-

The Japanese animator Kazuya Kanehisa was featured by Cartoon Brew in a piece with lots of fascinating insights about his work, based on “Showa-era” cartoons and aesthetics.

-

In Britain, the Cardiff Animation Festival revealed its program for 2026. It opens in April.

-

Last of all: we looked at three projects from China’s Flash scene — and at how that scene built the current Chinese animation boom.

Until next time!