Widowhood could be a formidable position in the Middle Ages. The death of a husband could unlock opportunities for women otherwise limited, like charge of a business, managing estates, and asserting her identity.

To begin our look at widowhood, let me introduce you to Margaret of Brotherton. Were you to be a medieval widow, you could hardly do better than Margaret.

First, a little history.

Margaret was born into royalty. Her grandfather was the formidable Edward Longshanks, otherwise known as the Hammer of the Scots. Her father, Thomas, was the king’s fifth son. By the age of seven, Thomas’ father was dead and his elder brother Edward (II) took the throne. Thomas was made the Earl of Norfolk and, until the birth of his nephew, was next in line for the throne.

To say that Edward II did not live up to his father’s reputation would be putting it mildly. His twenty-year reign was disastrous. He surrounded himself with much-loathed advisors, quarreled heavily with barons, and suffered a major defeat to Robert the Bruce in Scotland. Eventually, he was deposed by his wife, Queen Isabella of France, and his son, who took the throne as Edward III.

Thomas managed quite well for himself throughout all of this. Quite comfortably, in fact. He made the wise decision to back his sister-in-law and nephew when they seized the throne. Thomas was soon one of the young king’s closest advisors. For the next decade he remained by the king’s side. When he died in his late thirties, he left no living son. Finally, Margaret enters the picture. His successor was his daughter Margaret.

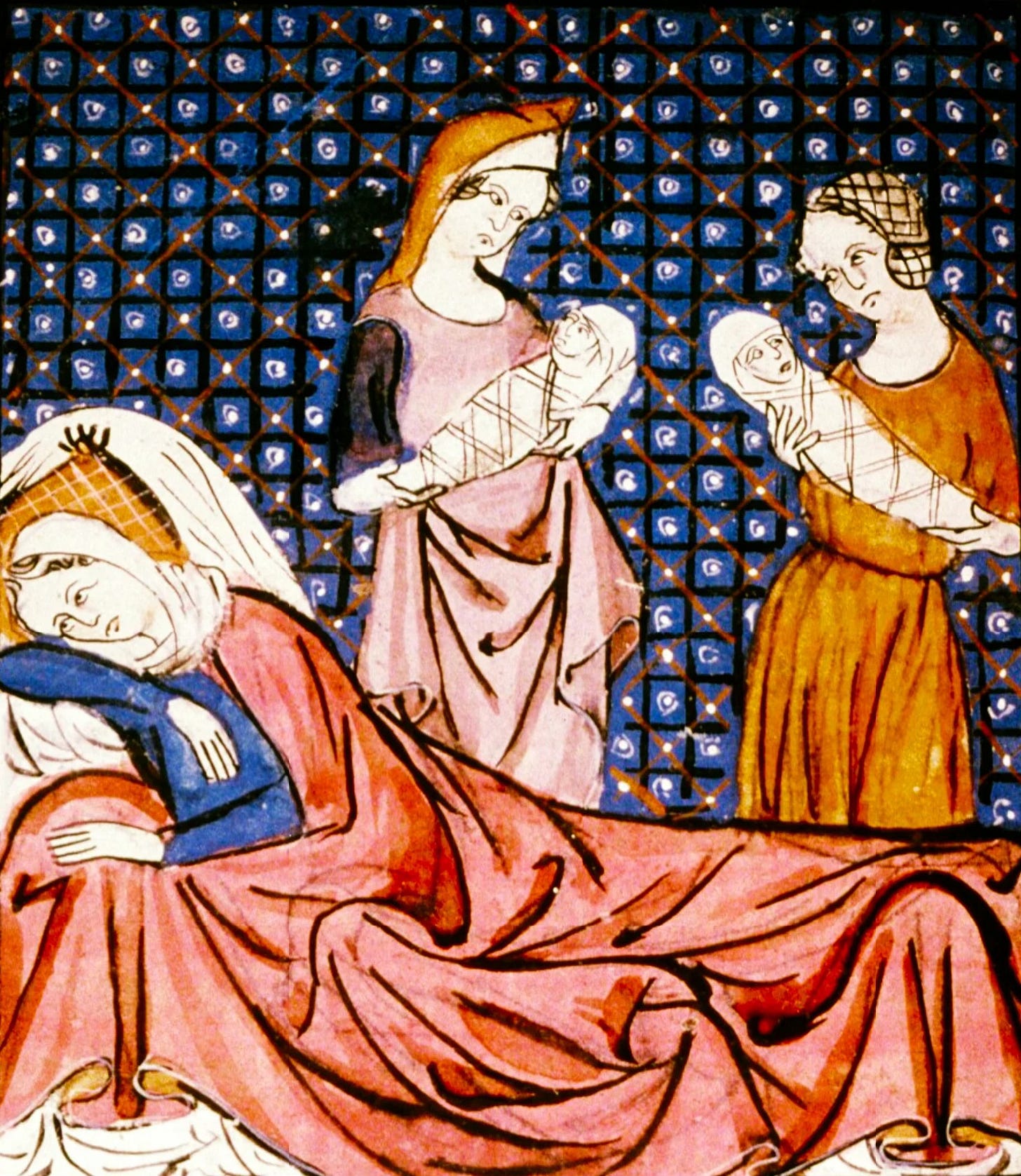

Margaret entered her first marriage at the age of thirteen. She married the twenty-year-old John Segrave, 4th Baron Segrave. When her father died a year into her marriage, she inherited her father’s estates, becoming both Countess of Norfolk and Earl Marshal of England.

Margaret and John had four children. Their first son John died young. Their second son John (why throw away a great name?) would die as a teenager. Their third child, Elizabeth, survived into adulthood, followed by another daughter who also died young.

Some fifteen years into their marriage, Margaret did something quite dramatic for the time: she petitioned for a divorce. Folks, I absolutely love her reasoning. She argued that the marriage contract was made before she was of age and therefore she could not consent.

Needless to say, her actions reverberated loudly throughout the country. Her cousin, King Edward III, forbade her from traveling to Rome to see the Pope and plead her case. So what did this intrepid thirty year old woman do? She disguised herself and set out for Rome by way of France. (Oh, and just by chance, once she reached France, she was helped by one Walter de Mauny. Walter would become her second husband, of course. Hold onto your hats.) Word reached the king of his cousin’s flagrant disregard for his travel ban. But before action could be taken, John Segrave, Margaret’s no doubt confused and humiliated husband, died. Margaret became a widow for the first time.

She wasted no time marrying Walter. She eventually reconciled with her cousin — no harm, no foul. (Though he did briefly place her under house arrest before deciding she would be forgiven.) She and Walter had three children. The first was Thomas, who drowned in a well at the age of five. Then came Anne and Isabel.

Margaret and Walter enjoyed eighteen years of marriage. He died in 1372, leaving Margaret a widow for the second time at the age of fifty.

So here we are at last: the promised topic. Widowhood. Margaret was a glorious medieval widow. Margaret is an extreme case, but a useful one. Her wealth and longevity make visible what widowhood could offer at its most expansive. Through her we can see what was possible, if rarely attainable, for other widows of her time.

By this point, Margaret’s estates were simply huge. Not only did she own the Brotherton estates inherited from her father, but she also held the Segrave lands from her first husband, as well as a portion of Walter’s estate. She spent most of her time at Framlingham Castle in Suffolk, where she reportedly led quite the lavish lifestyle. Household records from the time reveal a single year’s spending, which included over 70,000 loaves of bread, 151 pork carcasses, and twenty-four pounds of saffron.

By her seventies Margaret improbably had only two remaining heirs: her grandson Thomas Mowbray (son of her daughter Elizabeth Segrave), and his son Thomas the younger. Thomas the elder was granted title of Earl Marshal by Richard II, who had become king in 1377. Despite this, Margaret still styled herself Margaret Marshal or Countess Marshal. She may not have been allowed to perform her ceremonial duties as Earl Marshal, but by hell or high water she would claim her title. At the age of seventy-five, Margaret became the first English woman to be made a duchess.

Margaret died in 1399 nearing eighty years old, certainly a ripe old age for the time. In a twist of fate that could nearly be scripted, her heir never inherited her estates. Thomas Mowbray died of the plague in Venice some six months after his grandmother died. He was in exile by the king. His fourteen year old son, Margaret’s great-grandson, became her inheritor.

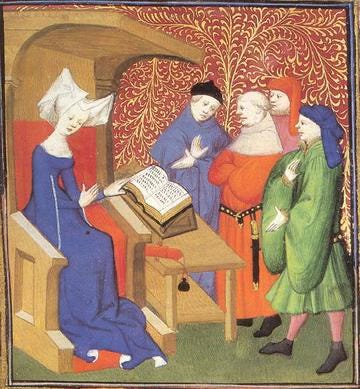

Margaret is an example of one of the most privileged kinds of widows. She came from nobility, lived a long and rich life, and had much more autonomy than the average medieval woman. Christine de Pizan, Europe’s first female writer, was also a widow who held close ties to the court. (Her astonishing The Book of the City of Ladies is well worth a read if you haven’t gotten to it yet.)

A widow who chose not to remarry or enter a convent could take a public vow of chastity. Some husbands even made the widow’s choice of remarriage for them. From the will of the Earl of Pembroke:

…and wyfe…remembre your promise to me take the ordre of wydowhood, as ye may be the better mayster of your owne, to performe my wille and to help my children, as I love and trust you…

Margaret’s circumstances were exceptional. Urban widows were not. In towns and cities, widowhood was a common experience. Their experiences, less spectacular but far more typical, reveal how widowhood functioned in daily medieval life.

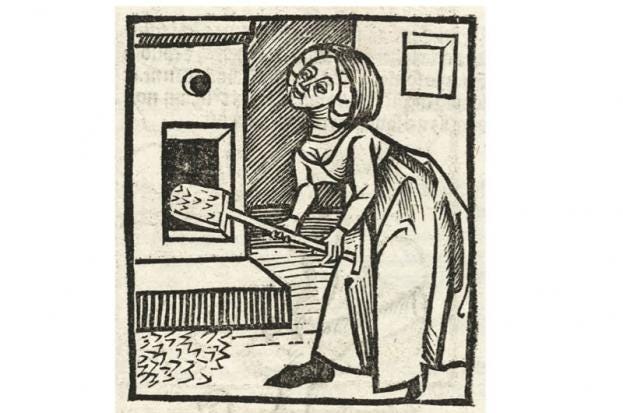

The wife of a merchant, baker, brewer, artisan or the like would have been no stranger to her husband’s work. She would have kept accounts, supervised apprentices, managed the household and in many cases work alongside her husband at his trade. So when he died, widowhood became not just a personal status for a woman, but a legally recognized one that reflected her familiarity with his business.

Urban custom was often kinder to widows than wives. Many towns allowed a widow to continue her husband’s trade, either for life or until remarriage. Guild records from London, Paris, York and Bruges show widows running breweries, textile shops, inns, and workshops. Guilds were keen to keep widows running businesses as it would contribute taxes, train apprentices, and keep money circulating. A competent widow maintaining continuity was good for business.

Widows in this class typically received a third of her husband’s movable goods as a dower. Unlike Margaret’s wealth, these assets tended to be more liquid: stock, tools, debts owed and coin. This gave the widow critical flexibility. She could invest, lend money, remarry strategically or, importantly, remain unmarried.

Records show widows suing debtors, negotiating contracts, and appearing in court without a male guardian. They signed documents with their own seals. Whereas married women were often legally subsumed under their husbands, widowhood granted some real independence.

A middle-class widow had to work hard. They were expected to keep their businesses afloat while raising children and defending property from opportunistic relatives. While remarriage was common, it was not inevitable. Some widows might remarry quickly for protection or capital; others remained single, calculating that a husband might dilute their control rather than enhance it.

Those who could not work or were homeless could find work and shelter in the form of an almshouse or hospital. These chaste widows cared for the sick and poor in exchange for meals and a bed.

A widowed peasant woman’s survival depended on her access to her late husband’s holding. In many manorial systems, widows were entitled to remain on the land for life, provided they paid rents and fulfilled labor obligations. Yet court rolls show widows acting as tenants, litigants, and heads of households. Their security was fragile. A bad harvest, a punitive fine, or the displeasure of a lord could undo a widow’s position quickly.

Remarriage amongst widowed serfs was common. Part of this was practicality; while women performed nearly all agricultural labor, a man was needed to hold the plough. Another factor was gossip. Had they had the means to hire a live-in servant to help with ploughing, eyebrows would have raised. Better to marry said servant than risk wagging tongues.

Widows were useful economically and socially, yet they were also unsettling to the medieval mind. They had known marriage, after all, meaning they had had sex. Preachers warned that once a woman tasted marital pleasure her appetite only grew more voracious. Hence we get depictions like Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, a veritable professional widow. She embodies many of the fears medieval people had about widows. Her exaggerated character confirmed what society already suspected. The Wife of Bath understands marriage as a negotiation, a means of extracting wealth and authority from a system designed to limit her. Chaucer mocks her but doesn’t silence her, mirroring the tension widows provoked in medieval life.

Widows could be a formidable force in the Middle Ages. Across classes, widowhood cracked open a door that marriage kept firmly shut. The death of a husband altered a woman’s relationship to property, labor, and authority. Widowhood brought no guarantees and little security, yet it could create a degree of independence otherwise unavailable to the medieval woman.