By Philip Pilkington

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine in late-February 2022 it has become clear that large changes were coming to the global financial and economic system. After the war started the United States and its allies announced that they would freeze the currency reserves that were owed to Russia and housed at central banks around the Western world. This was tantamount to a default, and the rest of the world took notice: now that the United States had weaponised the dollar system, any dollar holdings a country possessed could be frozen in the event of a geopolitical or military conflict with the United States[1].

Those who said that this risked the hegemony of the US dollar were not taken seriously at first. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the dollar saw a significant increase in value. By October of 2022, the broad US dollar index had risen around 10.8% since the beginning of the war. Yet those who pointed to these short-term moves misunderstood the critics of the reserve seizure. The reserve seizure represented a “structural break” in the system of US dollar hegemony. It dramatically increased the risk for any country to hold dollar assets and incentivised them to start looking for alternatives. Of course, the alternatives were few at first – as shown particularly by the issues the Russian central bank encountered holding renminbi and rupees in the months after the war[2]. In the short-term, it was no surprise that the world flocked back to dollar assets. But the structural break remained, like a patch of ice on a frozen lake that had thinned under the surface.

The Domestic Situation

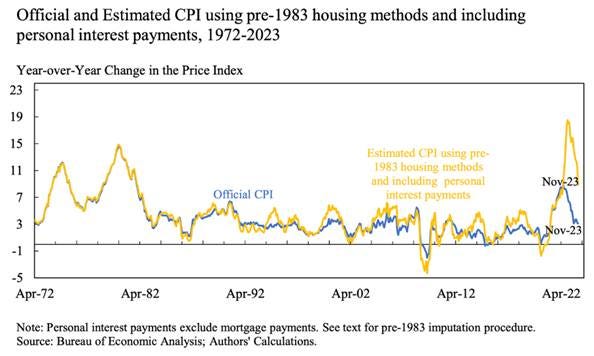

Although the dollar was trading firmly on international markets in this period, inflation was eroding living standards in the United States at a remarkable rate. That is, relative to other currencies, the dollar may have been doing well, but relative to the day-to-day needs of American consumers it was not performing well at all. According to the official numbers, inflation peaked around 9.1% in June 2022; however, the intensity of the price rises was so enormous that many Americans felt that these numbers were not telling the whole story and this led to a major divergence between opinion polling on inflation and the official numbers. One study published by Larry Summers and his colleagues argued that this divergence was because in 1983 the cost of repaying interest on loans had been removed from the official measures. Summers and his colleagues reconstructed the older method of measuring inflation – which counts interest costs, something that are particularly important in an economy as credit-dependent as the United States – and showed that it fixed this discrepancy. As the chart below shows, the metric that Summers and his colleagues came up with showed inflation peaking above 18%.

Source: Bolhuis et al 2024[3]

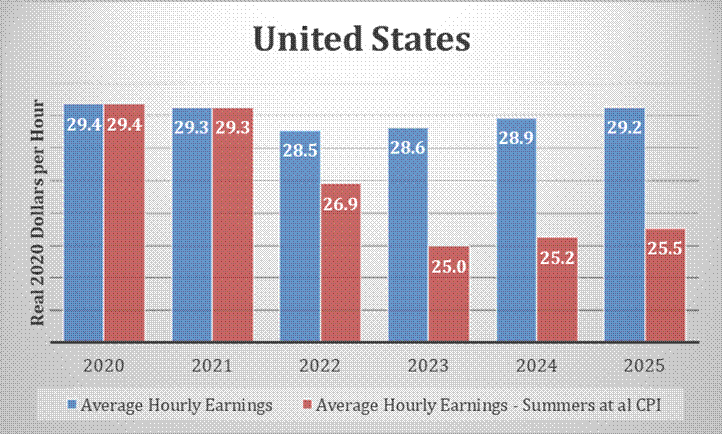

The data generated by this study suggests that the decline in American living standards has already been quite dramatic. We can see this more clearly if we calculate the evolution of real wages in the United States using the standard CPI metric and then also do the same using the metric arrived at by Summers and his colleagues[4]. These results are shown in the chart below.

Source: BLS

The difference between the two series is dramatic. If we are to believe the official statistics, real wages have been basically stagnant in the United States since 2020: inflation has wiped out any real wage growth. But if we accept the data generated by Summers and his colleagues, American real wages are around 15% lower in 2025 as they were in 2020. Intuitively, this lines up with the public opinion data. Initially, polling found that American voters were willing to give Trump a chance on inflation, but over time voters have come to disapprove of the president’s handling of the issue. As of January 2026, over 62% of people disapprove of Trump’s handling of inflation versus around 34% that approve. This is hard to square with official metrics of inflation which show prices only rising around 2.7% in 2025, Trump’s first year in office. These polling numbers make a lot more sense, however, if voters saw a 15% decrease in living standards under Biden and they expected Trump to return the economy to normal.

US Treasury Debt: The International Scene

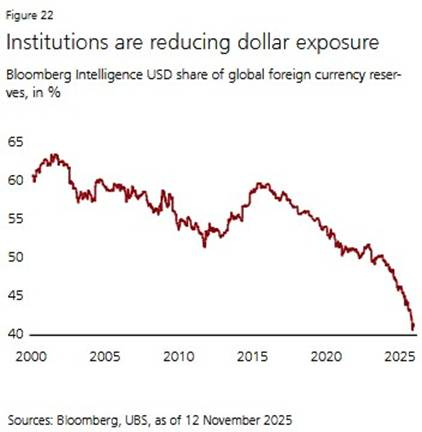

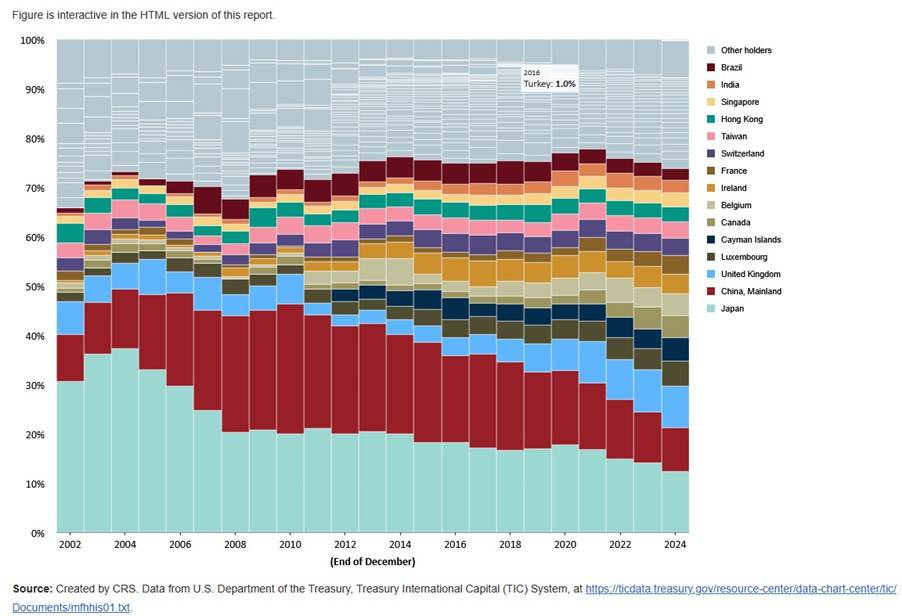

The structural break that occurred in the wake of the war in Ukraine did not give rise to an immediate run on the dollar. It did, however, cause countries to begin to consider alternatives. In the months after the war, various countries were reported to be quietly considering new reserve holding structures and even new trade settlement arrangements outside of the dollar. Russia became a sort of test case for a post-dollar economy that economists and central bankers around the world watched and discussed behind the scenes. It was when Donald Trump was elected to a second term in office that institutions began to act. As the following chart shows, when it became clear that Trump would take office with a more isolationist agenda institutions started to unload their reserve holding aggressively.

Source: UBS[5]

Yet while watching reserve holdings is instructive it can also be misleading. A country can decline as the hegemonic currency and even fall into crisis long before its currency is liquidated from global reserve holdings. Take the example of sterling. In 1949 the United Kingdom was facing a major currency crisis. Pound sterling had arguably not been the hegemonic currency since the 1930s and after spending enormous amounts of money fighting the Second World War, Britain was experiencing a major crisis. On 18 September 1949 the country had to devalue sterling from $4.04 per pound to $2.80, an enormous decline in the value of the currency. Yet in 1949 sterling still made up over 69% of global reserves while the US dollar only made up around 28%. What this example shows is that reserve holdings tend to be a lagging indicator of currency hegemony. A country can still have a large share of global reserves and be in the midst of a currency crisis. This is not widely enough understood today but the historical record is clear.

Nevertheless, Trump’s second term has certainly given countries an excuse to diversify out of dollars – an excuse that they have been looking for since the Biden administration weaponised dollar reserves. In recent months we have seen two events that have turbocharged this move away from the dollar. The first was in April 2025, when President Trump announced his “Liberation Day” tariffs. The main impact of this announcement was a sharp decline in American financial markets. Ultimately, this has given rise to a slow run on the dollar. Between January 2025 and December 2025, the dollar declined in value by around 6.5%. The second event that sped up the dollar’s decline as currency hegemon was in January 2026 when the Trump administration started to take an aggressive stance on taking over Greenland. In the aftermath of this, Deutsche Bank in Europe published a note suggesting that money managers should avoid dollar-denominated assets. This caused so much alarm that US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent had to call a chief executive of the bank to ensure that this did not reflect the official views of the institution[6]. At the same time, AkademikerPension a Danish pension fund announced that it would be divesting of all its US Treasury holdings due to heightened geopolitical risk[7]. All of this took place against the backdrop of America’s allies publicly signalling that they were moving away from Washington DC’s global leadership.

On paper the announcement by the Danish pension fund as insignificant. The fund itself was only offloading $100m of US Treasuries. Denmark itself has negligible holdings. In 2019 they held around 0.2% of all foreign US Treasury holdings and since then it has wound its holdings down to so little that they are not even detectable in the statistics. Nevertheless, the move by the pension fund – which no doubt had the backing of the Danish government, who in turn had the backing of the Europeans – sent a strong signal: America’s allies would no longer unquestioningly hold American assets. These events were exacerbated by problems in the Japanese government bond market that were not directly related to the geopolitical shifts in Europe. These problems could prove particularly import because, as the following chart shows, Japan is one of the largest single holders of US Treasuries in the world.

Source: United States Congress

The problems in the Japanese bond market had been ongoing throughout 2025. Japan has the largest public debt-to-GDP ratio in the world, at around 240% of GDP, yet it has been able to manage this with ease because of the extremely low inflation that the country had experienced for decades. This low inflation allowed Japan to borrow at extremely low interest rates. In recent years, however, Japan has seen moderate inflation return and this has led to a repricing of Japanese debt and a rapid decline in the value of the yen.

These crisis dynamics became severe in mid-January 2026 after the new Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi committed to increased spending and a reduction in taxes. On 20 January 2026, a major sell-off in Japanese debt began after a major 20-year bond auction failed to attract sufficient demand. Investors then became aware that any intervention in the Japanese bond market would result in a large amount of US dollar liquidity being injected into the global system at a time when the dollar looked unstable. If the Japanese sold currency reserves to prop up the yen this would result in more dollar liquidity because these reserves are mainly held in dollars. If the United States Treasury intervened directly, this too would require that the Treasury sell dollars into the international markets to prop up the value of the yen and bring down Japanese government yields.

The Catch-22 really kicked in when market analysts realise that if no one intervened and Japanese bond yields were allowed to rise, this rise in yields would be passed through to US Treasury yields. Goldman Sachs analysts calculated that every unexpected 10bp increase in Japanese government bond yields resulted in a 2-3bp increase in US Treasury yields – and in yields in other countries stitched into the dollar system, like the United Kingdom[8]. The volatility in Japan also shows why the analysts who dismiss relatively small sales of US Treasuries as meaningless are misguided. It took just $280mn of trading to cause significant volatility in the Japanese bond market, which is roughly $7.2tn in size, and cause a wipeout of $41bn worth of value[9]. Prices in financial markets are set aggressively at the margin. These markets are typically only a few bad auctions away from extreme volatility. This means that countries that have deep structural problems need be aware that these markets can turn on a dime.

After the turmoil in Japan, it has become clear just how fragile and how extensive the dollar-hegemonic system is. Because the system relies on extensive reserve holdings by other countries, any crisis in those countries immediately spreads to the United States because intervention in these countries requires the unwinding of their dollar positioning. Japan has already shown how vulnerable this system is if it falls into crisis. Given the large amount of US Treasury debt held by the United Kingdom and the extensive fiscal problems in that country, problems might emerge there too. Meanwhile, while the European Union is arguably more insulated from turmoil due to the large-scale nature of the euro-based currency system, geopolitical changes are pushing Europeans away from dollar assets.

Bubble Borrowing

These problems in the US Treasury market may seem bad enough – and certainly, in themselves, they constitute the looming potential for a crisis – but when we look at the broader picture America’s foreign borrowing looks even more fraught. The focus on America’s foreign sales of Treasury debt is understandable. Historically, the United States has financed its enormous trade deficits by issuing US Treasury debt to the rest of the world. This has colloquially become known as a trade in which the United States receive imports and the rest of the world receives IOUs from the United States. Since these IOUs are not backed by anything other than more IOUs, this is effectively a trust-based relationship.

Treasury IOUs are, however, at least somewhat predictable. A government bond may fluctuate in value, but it usually does not fluctuate in value too much. Even if a bond does fluctuate in value, it does not need to be sold. The holder of a US Treasury that promises x% interest for y years can hold that Treasury knowing that it will receive that interest no matter the mark-to-market value of the bond. A decline in the value of the US dollar is always a risk because the bonds ultimately pay out in dollars, but this is the case with any asset. US Treasuries are thus inherently less risky assets than almost any other offering.

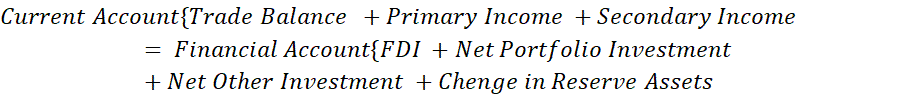

The problem today is that the United States are not primarily borrowing in US Treasury bonds anymore. For the past half decade, the country has relied increasingly on the sale of equities to other countries to prop up its trade deficit. To understand this let us briefly recall how the international account of a country works. The following equation shows the necessary relationship between the current account – that is, money flows in and out of the actual economy – and the financial account – that is, money flows in and out of financial markets[10].

In a country like the United States, we can simplify this much further. On the side of the current account, we can assume that primary income – investment income from abroad – is relatively stable and small, and secondary income – remittances and foreign aid – is insignificant. On the side of the financial account, FDI is largely stable and does not change too much, and other investment and changes in reserves make little difference. So, we are left with:

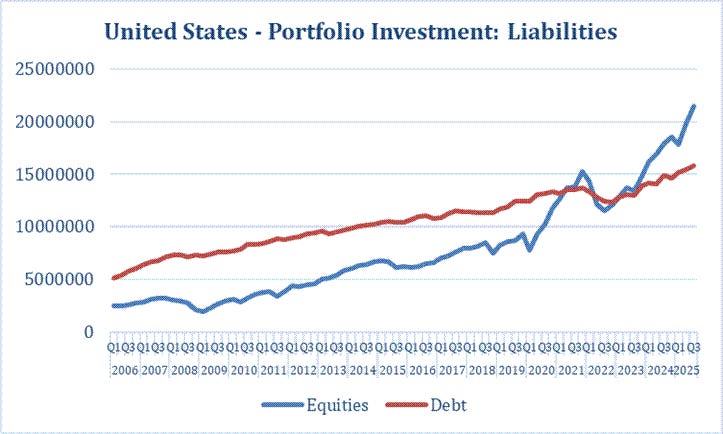

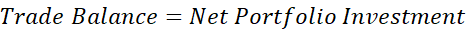

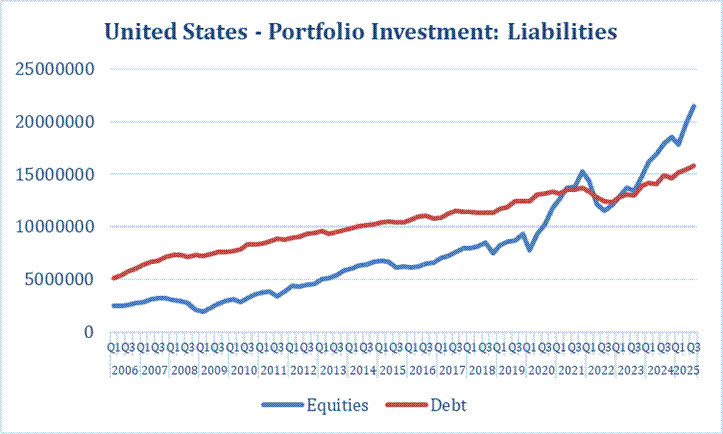

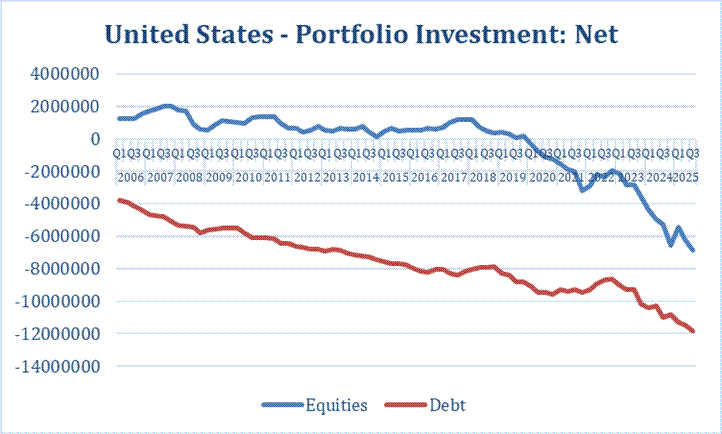

This represents a realistic picture of how the United States achieves balance on its international accounts: it balances a large trade deficit with strong net inflows into portfolio investment – that is, into markets for paper assets, mostly stocks and bonds. But when we turn to the data for the American international account, we see dramatic changes. These are best captured in the following two charts.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Here we see that around 2020, the United States started issuing enormous amounts of equities to the rest of the world. Prior to 2020, the United States had not relied much on equities to finance its trade deficit. In fact, the United States tended to run a net surplus in equities: that is, it bought slightly more foreign equities than it sold to foreign holders. In this period, the United States relied almost wholly on the sale of US Treasury debt to finance its trade deficit. Today, however, a significant amount of the American trade deficit is being financed by foreign equity issuance. On net, American equity issuance abroad is roughly half American debt issuance abroad. This is a dramatic development because equity markets are far more volatile than bond markets.

What this ultimately means is that if there is a crisis in the American stock market, this will very likely spread and become a general dollar crisis. If the United States sees foreigners dump equities en masse then the two sides of the equation laid out above will not balance. To bring these two sides into balance, the dollar would have to adjust downwards. The problem here is twofold. First, the American equity market may be in a bubble. In the past year more commentators are saying that the stock market is being driven by a bubble in technology stocks which in turn is being driven by hype around artificial intelligence that is not sustainable[11]. Secondly, since the Trump administration picked a fight with the Europeans over Greenland, European funds have signalled that they want to hold less American equities[12].

It is useless trying to predict the future, especially in financial markets. But the sheer extent of vulnerabilities in the American financial markets and the waning influence of the dollar should be cause for alarm. Other countries have now been trying to move away from the dollar hegemonic system for nearly four years – and have been doing so aggressively for a year. There is good reason to think that we have reached the “end of the beginning” of the decline in US dollar hegemony and that the next phase will be the terminal phase in which we see real financial and economic effects – effects which could be violent and politically destabilising. Markets seem to agree. At the time of writing, gold was trading above $5000 an ounce for the first time in history. We could be on the brink of a major geoeconomic event.

[1] https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2022/03/the-end-of-dollar-hegemony/

[2] https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2023/01/the-risks-of-russias-growing-dependence-on-the-yuan?lang=en

[3] https://www.nber.org/papers/w32163

[4] Note that we do not have access to the data in this study. Nor has the data been updated since the study was originally published. Instead, we have used the study to create our own proxy of the Summers et al data. This should provide a sufficient approximation.

[5] https://2026macro.vercel.app/UBS%20Year%20Ahead.pdf

[6] https://www.ft.com/content/15a3f2bc-539f-442c-a593-59e73c55017f

[7] https://www.reuters.com/business/danish-pension-fund-divest-its-us-treasuries-2026-01-20/

[8] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2026-01-25/japan-bond-market-crash-raises-alarm-for-global-interest-rates

[9] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2026-01-22/japan-bond-wipeout-was-triggered-by-just-280-million-of-trading

[10] We are abstracting from the capital account here because it is not particularly relevant.

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/money/2026/jan/10/ai-bubble-finances-crash-tech-meltdown-savings-pensions

[12] https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-greenland-europe-us-asset-holdings-treasurys-shares-sell-america-2026-1